Key highlights:

- SOVs are purpose-built vessels supporting offshore wind O&M and construction, typically about 80 meters long, accommodating 80-90 personnel, and operating on extended 14-day cycles offshore.

- Technologies like walk-to-work gangways, active heave-compensated cranes and hybrid energy systems enable safer, more efficient offshore operations while reducing environmental impact.

- The market is experiencing rapid growth, with new SOVs delivered annually, driven by offshore wind expansion, technological advancements and the need for flexible, resilient vessel fleets.

Editor’s note: Welcome to Offshore’s new educational “What Is…?” series. If you’re interested in contributing your insights and sharing industry knowledge with the next generation of offshore professionals, contact Chief Editor Ariana Hurtado at [email protected] for more information.

By Eloïse Ducreux and Hugo Madeline, Spinergie

With offshore wind capacity currently standing at out 40 GW, and projections reaching up to 211 GW by 2035, the sector is entering a phase of rapid industrial scaling. Within this context, service operation vessels (SOVs) and commissioning service operation vessels (CSOVs) have become the enablers of offshore wind deployment.

Positioned between crew transfer vessels (CTVs) and subsea units, these vessels play a role across both construction support and operations and maintenance (O&M). The SOV fleet is the fastest growing offshore vessel segment, highlighting a shift in offshore wind O&M toward more offshore-based strategies and longer-duration vessel deployment.

What are SOVs used for?

SOVs (and CSOVs) are purpose-built offshore vessels designed to support O&M and construction activities on offshore wind farms.

They typically measure about 80 m (262 ft) in overall length and can accommodate about 80 to 90 personnel on board.

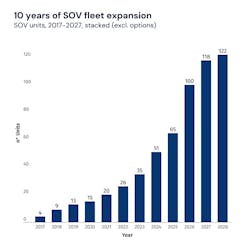

The first modern SOV entered service in 2017. Since then, they have become a core asset for offshore wind operators, especially on large and distant projects.

The primary role of the SOV is to act as a stable offshore base from which technicians can perform routine inspections, corrective maintenance, and small component replacement on turbines and offshore substations.

On the other hand, CSOVs were developed to compete with these larger vessels traditionally used in the oil and gas industry for turbine completion, array cable pull-in and commissioning tasks.

Unlike CTVs, which operate on a daily shuttle model from shore, SOVs remain offshore for extended periods. They typically operate on 14-day cycles, allowing technicians to live and work on site without returning to port every day. Indeed, distance from shore is a key driver of SOV use; beyond roughly 30 km, they are more widely used. Their operating model increases weather windows, reduces transit time and improves overall asset availability.

And as wind farms grow in size and move farther offshore, SOV use increases. This structural shift explains the rapid fleet expansion. In fact, 16 SOVs were delivered in 2024, about 14 in 2025, and 35 additional units are expected in 2026.

How do they work?

In many projects, SOVs can be used in combination with CTVs, rather than as a standalone solution. The SOV acts as a floating home base, providing accommodation, logistics and planning functions, while CTVs are deployed from the SOV to serve nearby turbines. This hybrid model improves flexibility and optimizes vessel utilization, especially on large wind farms where turbine clusters are spread over wide areas.

What are the challenges?

One of the first operational questions facing offshore wind developers and OEMs today is the choice of O&M strategy between CTVs, SOVs and helicopters. The decision is not binary and increasingly depends on site characteristics, distance to shore, weather exposure and the scale of installed capacity. While CTVs offer flexibility, and helicopters higher weather operability, SOVs provide offshore accommodation and integrated logistics that become critical as wind farms move farther offshore.

This choice has direct implications for fleet planning and contracting strategies. In some cases, developers reassess the timing at which a full SOV-based model becomes necessary, temporarily relying on CTVs before transitioning to an SOV once turbine volumes and intervention frequency increase. This staged approach adds nuance to demand visibility but does not fundamentally weaken the long-term role of SOVs in offshore wind O&M.

From a supply perspective, lead time remains a key stabilizing factor in the SOV market. New SOVs typically require about two years to be delivered, while offshore wind projects take on average about 3.5 years between final investment decision (FID) and commercial operation date. This gap allows vessel owners to align newbuild decisions with confirmed projects. In practice, a conservative owner can wait for FID, secure a long-term contract and still deliver the vessel in time for wind farm maintenance operations, enabling financing structures based on predictable revenues.

This dynamic differs from CSOVs as construction activities usually start around 1.5 years after FID, leaving less time to react once projects are sanctioned. As a result, owners targeting construction markets tend to accept a higher degree of uncertainty than O&M-focused SOV operators. Nevertheless, construction and maintenance requirements remain closely linked, and fleet strategies increasingly consider both segments together.

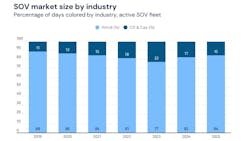

Finally, the interaction between offshore wind and oil and gas markets continues to influence SOV utilization. During the offshore wind expansion of 2020-2022, owners adopted different contracting approaches, ranging from long-term integrated wind charters to more speculative ordering without secured contracts. As project timelines shifted, some vessels entered the market without immediate long-term wind employment.

In response, some SOVs have been deployed on short-term contracts or redirected to oil and gas maintenance, either temporarily or for longer periods. This crossover reflects the multi-market capability of SOVs, providing flexibility for owners and resilience across offshore cycles, rather than indicating a structural weakening of offshore wind demand.

What's the SOV/CSOV outlook?

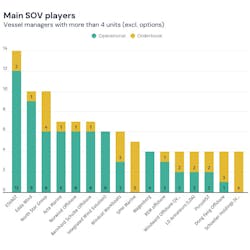

The fleet's long-term outlook is promising. Nearly 200 SOV/CSOV units are expected to enter the market by 2030, with a significant share set to work in the Asia-Pacific region. Dong Fang illustrates the APAC market dynamic with three units ordered. Yet, the aggressive expansion phase gives way to a more selective and strategic period.

While offshore wind remains the structural driver for SOV/CSOV demand, the short-term landscape is characterized by slower project sanctioning, tighter financing and rising competition. In this environment, owners are under pressure to lock in contracts early and, where possible, diversify into adjacent markets. Speculative tonnage faces the greatest exposure, reinforcing the need for cross-sector flexibility.

The rise of “energy vessels” captures this turning point; the industry is moving to a pragmatic fleet optimization. This evolution is less a signal of weakening fundamentals than of a maturing market, in which offshore wind continues to anchor long-term demand, while a gradual recovery in oil and gas activity supports utilization and provides complementary employment opportunities.

For more information, contact the authors or other Spinergie analysts at [email protected].

Offshore's "What Is...?" series

Young professionals in the offshore energy industry often encounter technical terms and acronyms that seasoned subject matter experts (SMEs) know by heart—but aren’t always clear to the next generation. Offshore’s new “What Is…?” educational series aims to bridge that gap by providing concise, practical explainers for emerging professionals.

Some of the most-searched topics include:

- What is an FPSO?

- What is a dynamic positioning (DP) system?

- What is a subsea production system?

- What is a blowout preventer (BOP)?

- What is a subsea tree (christmas tree)?

- What is an offshore riser system?

- What is directional drilling?

- What is a jackup rig?

- What is a subsea tieback?

If there’s an offshore energy subject you’d like to highlight in a brief explainer article (600-1,200 words), reach out to Chief Editor Ariana Hurtado at [email protected] for more information.

About the Author

Eloïse Ducreux

Eloïse Ducreux is an offshore sustainability analyst at Spinergie with three years of experience working on environmental topics in the offshore sector. She focuses on environmental assessment of offshore projects, including emissions modeling, impact studies and scenario analysis to support decarbonization decisions. Her work combines offshore market knowledge with a data-science approach applied to maritime activities and fleet-related emissions. She holds an MSc in data science and environment from The Institute of Aeronautics and Space.

Hugo Madeline

Hugo Madeline is a senior analyst at Spinergie with five years of experience in the energy sector. He specializes in offshore market analysis and industry insights, with a focus on decarbonization strategies, including fleet optimization and low-carbon technologies. He has expertise in offshore fleet operations and international and regional regulations. Hugo holds an MSc in energy transition from Mines Nancy Engineering School.