Offshore at 60: offshore drilling evolves to meet industry needs

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

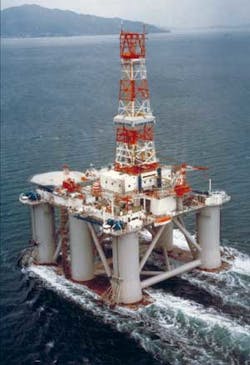

Over the past 60 years, as the offshore oil and gas industry has moved from bays and swamps to open water, drilling rig engineers have designed and built the facilities that allowed the industry to operate in ever-deeper waters.

Norton is uniquely qualified to comment on this history, and future trends. His company, Friede & Goldman, is one of the leading drilling rig engineering firms in the world. And Norton has more than 53 years of inshore and offshore experience in the design and construction of ships, semisubmersible and jackup drilling units, floating production units, posted drilling barges, supply boats, tug boats, and barges.

Norton graduated from Delgado Trades and Technical Institute (now Delgado Community College) in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1961 with a diploma in mechanical design. His first offshore-related job after graduation came from an opportunity with American Marine Corp., where he worked for three and a half years before joining Friede & Goldman.

During his employment with American Marine Corp., he designed offshore supply vessels for Tidewater, Twenty-Grand, Arthur Levy, and Cheramie Brothers Bo-Truc Service; tug boats for Twenty-Grand and Belcher Towing; and deck and tank barges for numerous customers.

His current responsibilities at Friede & Goldman include the development of preliminary design concepts and assisting both the engineering and drafting departments in the development of these designs. In addition to the above duties, he participates in interface conferences with clients. Norton's particular expertise in the offshore area is in drilling rig and system design and development, including the preparation of specifications for drilling rigs and its utilities and services.

The interview, which took place at Friede & Goldman's office in Houston, is part ofOffshore's partnership with the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum at Texas A&M University, and undertaken under the auspices of Offshore's 60th anniversary commemoration and the library's exhibit, "Offshore Drilling: The Promise of Discovery," which is scheduled to open this month.

Offshore: You've had a great career in the offshore drilling industry. Looking back, what have been some of the primary drivers for changes and advances in technology and equipment?

Norton: To drill in deeper water, and to drill deeper wells in harsher environments, with varying environmental conditions – these are the driving factors for the changes. We started out in inland shallow water, and then went to offshore in 100 ft, and now we're designing rigs for up to 12,000 ft of water.

Offshore: Who, or what, is driving the new specifications for the industry?

Norton: It's generally a mix. The largest involvement would be the drilling contractors themselves, but, in so many cases, they are bidding on contracts for a specific operator who has specific wants and needs for a particular field or a particular well to be drilled. So that will, a lot of times, influence the design or changes to the design. We have a series of standard designs that we modify to suit the client. There are other factors. The regulatory bodies do come into play because there are new rules coming out all the time.

Offshore: What would be the top two or three things that you've seen in terms of changes or evolution in the offshore drilling industry?

Norton: The earliest one that I remember is in the early '70s when drilling was in the North Sea. The UK came up with a requirement that the rigs had to meet a 100-ft wave with five feet of clearance from the crest of the wave to the underside of the structure, with a 100-knot wind. The difference between the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico is that the North Sea folks don't evacuate for storms because the winter storms are quite frequent and they'd never get any drilling done. So, they man the rigs all the time, but they wanted to make sure the rigs were capable of withstanding these storms. Therefore, these rules came out. They required us to change our designs in order to get this clearance, and most of those rigs are semisubmersibles, and they had to be high enough to clear the waves and also to have the stability required to operate under those conditions. Now, during the Gulf of Mexico hurricane season, they evacuate the rigs, but, still, the design was changed to accommodate any theater because the rigs are known as mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs). You can operate anywhere in the world, and that set the tone for rig operational requirements.

Offshore: Talk about moving into deep water – the migration from, say, 500 ft to 10,000 or 12,000 ft. In your opinion, what is happening to make this migration to deeper waters possible?

Norton: Well, as you know, the deep water is generally further from shore, you're further from your shore base, so you need to go on location with as much of your drilling program – if not all of your drilling program – as you can carry, because the supply-boat runs get longer, bigger boats are required, operations are more costly. So, when you start increasing the variable deck loads, along with payloads, fuel, pipe, casing, and expendables, the rig has to get bigger. And, of course, as the rig gets bigger, it weighs much more, and it has to operate at a certain draft for stability considerations, so there's a design spiral there, and the final product winds up as a compromise with what you started with.

Offshore: Talk to us about how blowout prevention (BOP) technology has evolved and changed.

Norton: Well, the earliest preventers that I remember were 10,000, 5,000 and 2,000 psi ratings. Now they're up to 10,000 and 15,000 psi ratings, and there are some on the horizon with 20,000 psi ratings. So, as the wells get deeper, and as we find these higher pressure formations, they will become standard within the industry – for certain wells, you'll have to have the higher rated BOPs. The early ones had several rams and one annular, and now they have up to 6 rams and, with some of the new regulations coming out of the Macondo incident, I'm hearing that it's now 7, maybe 8, rams. So, as the stacks have gotten bigger, they've gotten heavier over the years. This has a knock-on effect for the handling equipment – and these increases come off your variable deck load.

Displaying 1/4 Page 1,2, 3, 4Next>

View Article as Single page

About the Author

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Bruce Beaubouef is Managing Editor for Offshore magazine. In that capacity, he plans and oversees content for the magazine; writes features on technologies and trends for the magazine; writes news updates for the website; creates and moderates topical webinars; and creates videos that focus on offshore oil and gas and renewable energies. Beaubouef has been in the oil and gas trade media for 25 years, starting out as Editor of Hart’s Pipeline Digest in 1998. From there, he went on to serve as Associate Editor for Pipe Line and Gas Industry for Gulf Publishing for four years before rejoining Hart Publications as Editor of PipeLine and Gas Technology in 2003. He joined Offshore magazine as Managing Editor in 2010, at that time owned by PennWell Corp. Beaubouef earned his Ph.D. at the University of Houston in 1997, and his dissertation was published in book form by Texas A&M University Press in September 2007 as The Strategic Petroleum Reserve: U.S. Energy Security and Oil Politics, 1975-2005.