Offshore at 60: offshore drilling evolves to meet industry needs

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Over the past 60 years, as the offshore oil and gas industry has moved from bays and swamps to open water, drilling rig engineers have designed and built the facilities that allowed the industry to operate in ever-deeper waters.

Norton is uniquely qualified to comment on this history, and future trends. His company, Friede & Goldman, is one of the leading drilling rig engineering firms in the world. And Norton has more than 53 years of inshore and offshore experience in the design and construction of ships, semisubmersible and jackup drilling units, floating production units, posted drilling barges, supply boats, tug boats, and barges.

Norton graduated from Delgado Trades and Technical Institute (now Delgado Community College) in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1961 with a diploma in mechanical design. His first offshore-related job after graduation came from an opportunity with American Marine Corp., where he worked for three and a half years before joining Friede & Goldman.

During his employment with American Marine Corp., he designed offshore supply vessels for Tidewater, Twenty-Grand, Arthur Levy, and Cheramie Brothers Bo-Truc Service; tug boats for Twenty-Grand and Belcher Towing; and deck and tank barges for numerous customers.

His current responsibilities at Friede & Goldman include the development of preliminary design concepts and assisting both the engineering and drafting departments in the development of these designs. In addition to the above duties, he participates in interface conferences with clients. Norton's particular expertise in the offshore area is in drilling rig and system design and development, including the preparation of specifications for drilling rigs and its utilities and services.

The interview, which took place at Friede & Goldman's office in Houston, is part ofOffshore's partnership with the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum at Texas A&M University, and undertaken under the auspices of Offshore's 60th anniversary commemoration and the library's exhibit, "Offshore Drilling: The Promise of Discovery," which is scheduled to open this month.

Offshore: You've had a great career in the offshore drilling industry. Looking back, what have been some of the primary drivers for changes and advances in technology and equipment?

Norton: To drill in deeper water, and to drill deeper wells in harsher environments, with varying environmental conditions – these are the driving factors for the changes. We started out in inland shallow water, and then went to offshore in 100 ft, and now we're designing rigs for up to 12,000 ft of water.

Offshore: Who, or what, is driving the new specifications for the industry?

Norton: It's generally a mix. The largest involvement would be the drilling contractors themselves, but, in so many cases, they are bidding on contracts for a specific operator who has specific wants and needs for a particular field or a particular well to be drilled. So that will, a lot of times, influence the design or changes to the design. We have a series of standard designs that we modify to suit the client. There are other factors. The regulatory bodies do come into play because there are new rules coming out all the time.

Offshore: What would be the top two or three things that you've seen in terms of changes or evolution in the offshore drilling industry?

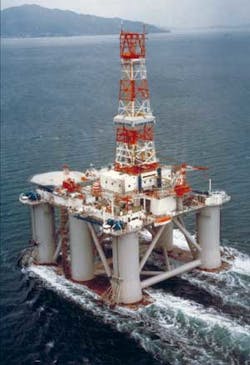

Norton: The earliest one that I remember is in the early '70s when drilling was in the North Sea. The UK came up with a requirement that the rigs had to meet a 100-ft wave with five feet of clearance from the crest of the wave to the underside of the structure, with a 100-knot wind. The difference between the North Sea and the Gulf of Mexico is that the North Sea folks don't evacuate for storms because the winter storms are quite frequent and they'd never get any drilling done. So, they man the rigs all the time, but they wanted to make sure the rigs were capable of withstanding these storms. Therefore, these rules came out. They required us to change our designs in order to get this clearance, and most of those rigs are semisubmersibles, and they had to be high enough to clear the waves and also to have the stability required to operate under those conditions. Now, during the Gulf of Mexico hurricane season, they evacuate the rigs, but, still, the design was changed to accommodate any theater because the rigs are known as mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs). You can operate anywhere in the world, and that set the tone for rig operational requirements.

Offshore: Talk about moving into deep water – the migration from, say, 500 ft to 10,000 or 12,000 ft. In your opinion, what is happening to make this migration to deeper waters possible?

Norton: Well, as you know, the deep water is generally further from shore, you're further from your shore base, so you need to go on location with as much of your drilling program – if not all of your drilling program – as you can carry, because the supply-boat runs get longer, bigger boats are required, operations are more costly. So, when you start increasing the variable deck loads, along with payloads, fuel, pipe, casing, and expendables, the rig has to get bigger. And, of course, as the rig gets bigger, it weighs much more, and it has to operate at a certain draft for stability considerations, so there's a design spiral there, and the final product winds up as a compromise with what you started with.

Offshore: Talk to us about how blowout prevention (BOP) technology has evolved and changed.

Norton: Well, the earliest preventers that I remember were 10,000, 5,000 and 2,000 psi ratings. Now they're up to 10,000 and 15,000 psi ratings, and there are some on the horizon with 20,000 psi ratings. So, as the wells get deeper, and as we find these higher pressure formations, they will become standard within the industry – for certain wells, you'll have to have the higher rated BOPs. The early ones had several rams and one annular, and now they have up to 6 rams and, with some of the new regulations coming out of the Macondo incident, I'm hearing that it's now 7, maybe 8, rams. So, as the stacks have gotten bigger, they've gotten heavier over the years. This has a knock-on effect for the handling equipment – and these increases come off your variable deck load.

Offshore: From where you started, did you ever conceive the weights and the scales that you're working with?

Norton: No, because, in the beginning, we had, maybe, two 75-ton bridge cranes that handled the BOP stack. Of course, you handled them in two pieces, and, because they were tall (what we thought were tall back then), you had to assemble and test them on the well center before you ran them. And then, later on, in the early 1980s, a Norwegian company came up with a transporter that was like a giant forklift truck, which permitted the stack to remain assembled. This was an improvement because, every time you broke the joint between the BOP and lower marine riser package (LMRP), when you reassembled it, you had to retest it because you had to prove that the joint could hold the pressure rating in the stack. And you were able to lower the stack before you got under the drill floor, and this made running faster. Of course, they've grown now to where the handling equipment is rated at 500 tons – so we've gone roughly from 150 to 500 tons in the space of 45 years.

Offshore: Is there a ceiling to this?

Norton: I'm sure there is, but I wouldn't even want to venture to say what it is because, like I said, it has increased so much over the past 40 years. What's going to happen in the next 40? I'm sure they'll come up with something.

Offshore: Talk to us about risers and their role in these innovations.

Norton: The riser's purpose is to return the mud and the cuttings from the wellbore back to the surface, where the mud processing system will remove the cuttings and any gas that might be in the mud – and then the mud is reused because it's a very expensive commodity. The earlier risers were bare, and they depended strictly on the riser tensioner system to support the risers (because of the weight of the riser and the mud, the riser can't support itself). And you had top tension, which was not that much back then, but it was considerable. But as the risers got longer because of the deeper water, they had to get heavier because of the wall thickness due to the hydrostatic head on the bottom of the riser. Also, along came the buoyancy jacket, which was strapped to the individual riser joints, which, in conjunction with the top tension, made the longer strings feasible. As water depths increased, the wall thickness of the riser increased, and soon the weight became a factor and you didn't have sufficient top tension, you didn't have sufficient buoyancy. So, they came along with the tapered string, where, as the riser length increased, the lower sections had a heavier wall, and, as you went up the riser, the wall got thinner, and, coupled with the increased buoyancy jacket diameter, you were able to have a tensioner system that was reasonable.

If something happened and you lost the mud that was in the riser (either due to a lost circulation incident in the formation, or if the riser parted), then there was a riser fill-up valve that opened and allowed seawater to flood the riser, which reduced the chances of a riser collapsing. When you have all this buoyancy and all this tension, if something happens, like an unscheduled disconnect between the stack and the seabed or the stack and the LMRP (and with the massive amount of tension right now – it's up to 4,000 kps), you could drive the riser through the drill floor. They have a sensing system, called the anti-recoil system, which senses this minute increase in acceleration, and it shuts the riser tensioners down and prevents this from happening. The riser also supports the choke and kill lines from the stack to the rig. Also, there's hydraulic lines that keep the accumulators that control the BOP functions charged, and a few other lines on it.

Offshore: Talk about the introduction of dynamic positioning (DP) and how that has affected design and what you do.

Norton: As rigs moved into deeper water, the mooring system became less effective, and, because so much of the strength of the wire, or the chain system, was consumed by just supporting itself, it reached a point where we had to do something. Then came dynamic positioning. Now, they have several different categories of dynamic positioning: DP-2 and DP-3. Right now, the most common is the DP-3, which has the most onerous set of regulations, because it requires redundancy in all systems. You have separation of the power generation equipment, the switchgear equipment, the distribution system, and the thrusters. The rig has to be able to lose a whole engine room, or a whole switchgear room, or a whole thruster room. So, to maintain a "station" in a reasonable environmental situation, you have to have sufficient generation capacities to accomplish this. This means that more space is required for three and four engine rooms and switchgear rooms. It increases the size of the vessel just to accommodate all of this redundancy.

Offshore: How have the power requirements escalated over time?

Norton: In the early '70s, rigs generally had four 2,000-hp diesel generator sets that were able to handle all of the drilling operations and the hotel requirements. And you had a small crew, maybe 80 to 100 people. The major consumer was the drilling equipment. In the 1980s, the rigs were still moored but they had thrusters to assist the mooring system during high environmental conditions and the power requirements were 6,000 to 8,000 kW. Now, with DP, you are talking about power requirements of 40,000 to 45,000 kW, with the largest consumer being the DP system.

Offshore: What are the latest advancements regarding power?

Norton: Engine manufacturers have always strived to improve the economy and to lower the fuel consumption of their engines. That's been a big help because we had four engines in the '70s, and now we have maybe six or eight engines but we've quadrupled the horsepower. So, we've been able to go with slightly larger, more efficient engines, which helps as they get bigger and heavier.

Offshore: Let's talk about the drill rig market today. What are the trends? What are you seeing in semisubmersible drillships?

Norton: Right now, it looks like the biggest market is for jackups and drillships. The semi design market, for us, has been fairly flat. We had quite a few semis built several years ago, but, presently, we don't have any under contract. Our biggest market is the jackups, and we are also offering a design for a drillship now. And we see other drilling contractors building multiple copies of drillships. Jackups and drillships seem to be the two big plays.

Offshore: What are the increasing demands that operators are placing on drill rig functionality?

Norton: Before, you drilled the well and then somebody came in and tested the well to determine if it was a viable formation – or they would run extended well tests, and they would have to come in and lay the pipeline. There were a number of various operations that had to be done before the oil was delivered to a pipeline or to shore. Now, however, once the rig on location, operators want the rig to do as much as it can. So, even though the day rate may be higher now, I think that the more the rig can do, once it's on location, it's more cost efficient.

Offshore: So what are the rig services that operators are looking for now?

Norton: Most of our designs can do completions, well tests, and set the trees. They can't lay pipe yet, because that's a very specialized industry.

Offshore: What opportunities are out there for independents or new operators?

Norton: There are still some small fields in shallow waters that the majors won't touch because they're just too small. Jackups have lower day rates, can operate in shallow waters, and most of them have a 20,000 to 25,000-ft drilling capacity. Some of the big ones can go up to 35,000 ft. So, in 400 ft or less, they're the most cost-effective piece of drilling equipment. There are various solutions for small fields – you can always put in a platform, or, as you go a little bit further out, you have the floating production, storage and offloading units (FPSOs) and the floating production units (FPUs). And then there is the floating production facility (FPF), which is a marginal field production unit with a minimal production equipment installed.

Offshore: How has the industry workforce changed over the years?

Norton: Back in the mid '80s, when we had a terrible downturn for the industry, a lot of people were let go. Many found jobs in other industries, and, when the market came back, those folks didn't return to the industry. Consequently, the industry lost a lot of experienced people. And the people who replaced them weren't always oilfield-related people. They were younger people without much experience. There are still some of the old fellas, like me, who managed to survive, and we learned over the years what worked and what didn't work. A lot of these newer people don't have this experience, so there's a lot of reinventing of the wheel or mistakes being made. Now, some of the retired folks are coming back as contractors – sometimes working for the same companies that they worked for originally. The trend seems to be for companies to have a smaller, core workforce and then to supplement it with contractors.

Offshore: What recommendations do you have for someone just out of college who may be interested in this industry?

Norton: They need to get the experience of working on a rig; get a feel for what the equipment is, what it looks like, what it does. I would suggest that they try to work a year or two in the field, and gain that experience. Do the grunt work. Don't expect to be a manager right off the bat. Learn from the bottom up. Learn the ins and outs, and learn what works, and what doesn't work. That way you've built up a mental library and can say, "Hey, we did this 25 years ago and it worked or didn't work …" or "we tried it and it was a failure …" That would be my suggestion.

Offshore: How has the safety culture changed over the years?

Norton: On the earlier rigs, most things were done manually, and most of accidents occurred either on the drill floor or in the derrick or on the pipe rack. You had to move the pipe and casing from the pipe rack to the floor, up the pipe slide. It was all done with chains and tuggers, and you had guys pushing pipe around, moving it into the mouse hole. You've seen pictures of the guys throwing the chains and pushing the tongs in, and then torquing up the joints. This was where a lot of fingers were lost, and a lot of toes were lost from pipe dropping on them. Guys got hurt, but it was an accepted way of life. But now the culture has changed to where you have virtually no people on the floor. Everything is automated. The crane operator puts the pipe in the catwalk machine, and it delivers it to the floor. The various devices that they have now can build the stands and set the stands back into the setback area. When they are ready for another stand, the handling system in the derrick will move the pipe and stab it. The iron roughneck makes up the joint, dopes the joint, spins it up, torques it. Drilling is all controlled by the driller and assistant driller in the cabin. So there are very few people on the floor where the accidents used to occur.

Offshore: Going forward, where do you see industry improvements happening?

Norton: With a lot of equipment working simultaneously, anti-collision devices need to be in place and working. The people operating the equipment have to be able to know when it's not operating properly and have either some way of shutting it down or bringing it to a safe condition. They need to know how to operate it if the computer goes down. All of this equipment is computer-controlled now, with PLCs and such. If it goes down, the rig shuts down until a technician can get there to find out what the problem is. So I think that's going to be the next big challenge – making certain there's sufficient redundancy and that it can operate so that the rig doesn't stop drilling. The operator will only allow a certain amount of down time, then the rig goes off payroll.

Offshore: Are there water depths that are not feasible?

Norton: As long as operators have finds of sufficient commercial value, they will find a way to extract the oil or the gas from those formations. There's been talk about these submersibles… these fully submerged drilling rigs and such. Some company is going to figure out how to do it.

Offshore: Looking back over your career, were there any "wow" moments?

Norton: Every new project always brings in something, such as a new piece of equipment or a new process, or something that wasn't available two years ago. So it's been just a continual wowing, so to speak. There's always something new to make performing the various tasks better, faster, or safer. Doing things faster is the name of the game, because the operator is always pushing for the drilling contractor to drill the most hole in the least amount of time.

About the Author

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Bruce Beaubouef is Managing Editor for Offshore magazine. In that capacity, he plans and oversees content for the magazine; writes features on technologies and trends for the magazine; writes news updates for the website; creates and moderates topical webinars; and creates videos that focus on offshore oil and gas and renewable energies. Beaubouef has been in the oil and gas trade media for 25 years, starting out as Editor of Hart’s Pipeline Digest in 1998. From there, he went on to serve as Associate Editor for Pipe Line and Gas Industry for Gulf Publishing for four years before rejoining Hart Publications as Editor of PipeLine and Gas Technology in 2003. He joined Offshore magazine as Managing Editor in 2010, at that time owned by PennWell Corp. Beaubouef earned his Ph.D. at the University of Houston in 1997, and his dissertation was published in book form by Texas A&M University Press in September 2007 as The Strategic Petroleum Reserve: U.S. Energy Security and Oil Politics, 1975-2005.