DP integration illustrates larger need

Eldon Ball

Senior Editor, Technology and Economics

The dynamic positioning (DP) system is one of the more critical technology systems on a deepwater drilling unit. Ultra-deepwater semisubmersibles and drillships are primarily dynamically positioned, and they rely on thrusters managed by complex computer systems to keep the rig on location – constantly in place over a very small radius. The deeper the water, the smaller that radius effectively becomes, making the task even more difficult.

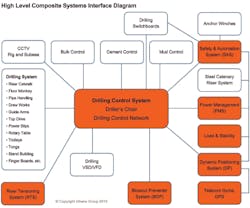

As complex and vital as it is, the DP system is not a standalone technology. It interfaces with numerous other systems on a drilling rig, and that integration with other systems is an increasingly critical process in itself.

Keeping DP systems at peak and most reliable performance, and integrating those systems with all others on an offshore drilling unit, have become a major focus of the offshore operators who contract the rigs, and hence for the offshore drillers who build and operate them. For an understanding of how DP systems work and how software integration is moving into greater focus for offshore operators,Offshore talked to Don Shafer, Chief Technology Officer and Chief Safety Officer at the Athens Group, about DP control systems technology and the growing focus on control systems software and hardware integration.

Offshore: Start with the DP system and how that ties in to the integration question.

Shafer:Of all the technology offshore, DP is probably the most mature and in terms of control systems, probably the most reliable. Manufacturers have taken lots of lessons learned from their customers. For example, almost all cruise ships used today are dynamically positioned. The key area of dynamic positioning that we focus on at Athens Group is the functioning of the control systems, ensuring that all those are working to spec, fulfilling all the sea trails, etc. Further, our services extend to the commissioning of all the drilling equipment itself. We have to help ensure that the interfaces to the other onboard systems work.

Although the drill floor is drilling system centric, the interaction with the dynamic positioning system is very important because when you’re drilling, one of the things you have to be able to activate an emergency disconnect. To do that, the driller has to understand what’s happening with the drilling system, so that they don’t drive off before they’re disconnected. Therefore, you have to have an interface from the DP to the drilling systems. You also have to have an interface to the power management system, since one of the major areas it’s controlling is the dynamic positioning system.

Offshore: A lot of systems that have to talk to each other.

Shafer:Yes. When you put a power management system on a drilling platform – a drillship or a semisub – you have to put in a system of designated algorithms that specify what happens whenever there’s a problem. For example, in the North Sea, the sea state may suddenly go from three-meter to eight-meter waves. When that happens, you know that as the water swells up through your moonpool, it’s going to hit the crown block. At that point in time, you’ve got most of your power to your thrusters, so that you can maintain position. You don’t want to have a “drive off” incident and rip the BOP out of the ocean floor. So power management is an important aspect – an important interface.

Offshore: Are the interfaces built in?

Shafer:Not often. Of all of the equipment that we work with, there are almost no equipment manufacturers out there today that look at all the interfaces. They know that their equipment works, but are they looking at the interfaces? We look at the interfaces, and the requirements for those interfaces. That’s the real key. Regarding DP, we focus on making sure that sea trials are successful, that we’ve got the correct requirements in place, and that the DP system functions well in a drillship that’s going to be drilling in 10,000 ft of water, for example.

Offshore: And this is one of the areas you’re addressing?

Shafer:Yes. One of the things we’re advocating – and something that more and more of our customers are taking an interest in – is contractually specified software testing and integration requirements. We’ve found that, historically, contracts go into greatly detailed specifications on all kinds of things, even down to the specs on painting the vessel, but they carry no specifications on software. And that’s still pretty much true today. It’s pretty amazing. Would Airbus build their next generation of aircraft without having specifications on software?

Offshore: Why is that the case?

Shafer:Because software is invisible, it becomes an afterthought. We’re working now primarily with the major offshore operators to bring software specs into the contract. Because it really is the duty of the majors to get software specs started. I gave a talk at the IADC meeting two years ago about some things we’ve done on non-productive time (NPT), and I mentioned the fact that we don’t have a baseline to measure NPT against. One of the executives from an operator there asked who’s responsible for fixing that, and I said, “You are. As an operator, you’re responsible.”

The goal is to help equipment suppliers integrate their products and processes so that they can communicate and coordinate more efficiently and effectively.

Offshore:And that’s the case with software integration, as well?

Shafer:Specs get written on a basis of time to oil – within accepted industry standards, of course – but there is no connection in the contract between all the pieces and parts of the drilling operation that have to work together for drilling to be efficient and safe. So, we’re working with the majors at the very beginning in setting the contractual software specs. And they are putting them into their contracts. If you just say “I want a dynamic positioning system,” then you get a dynamic positioning system. If you want a dynamic positioning system that’s integrated with the power management system, a kinetic energy management system in place, and you’re going to do these types of emergency disconnect procedures, then everything has to work together. At that point, you’re going to see that you need to tie it all together from the beginning.

Offshore: What else?

Shafer:Then there’s the idea of putting together a life cycle. We understand that if we’re going to work with an engineering company, they’ve got their sequence of project steps they typically go through. We worked with one operator in the Gulf of Mexico and they just didn’t want to hear about software. They didn’t want to talk about it. But their production facility was going to have six separate networks on it. It’s got an IT network that would rival any office building in the world, and it just happened. It just grew organically. It’s pretty amazing that it even got done.

Then there’s the case of unintended consequences. Let me give you an example. An offshore vessel operating in the Gulf of Mexico had an older, but reliable, legacy DP system. The vessel owner wanted to upgrade the DP system but, because the vessel was on contract, down time for the upgrade needed to be kept to a minimum. The owner purchased a “Plug and Play” upgrade, which would require only two days of downtime to install and commission. However, the upgrade did not interact predictably with the legacy hardware and did not allow porting of the legacy configuration parameters. The result was that the timeline for DP commissioning was extended from 2 days to 3 weeks. As a result, the vessel owner lost his contract.

Offshore: Is the process changing?

Shafer:Yes. As we look at putting these specifications into the contracts, the need is to put into the process some software vendor specifications, and we’re doing that on a regular basis now. We do formal capability assessments of equipment vendors’ software development groups whose equipment is on our clients’ drilling or production facilities. We’re doing these types of assessments for the majors on the rigs that they’re going to be contracting.

Specifically, we’re going in and asking, what acceptance testing, configuration management, regression testing is done? Does the supplier have system or integration specifications? Do they have a signal list or an alarm list? Surprisingly enough, you can walk into a software development group and ask for a copy of their alarm list and they give you a blank look. We want an alarm list so that when we do the final acceptance and we do all the testing, we know what alarms to test for and what should be annunciated and where they should be annunciated. If there are too many alarms and you start turning alarms off, even the annunciation of them, you get to the point where you ignore all the alarms, and you ignore what’s important. If you’re ignoring the alarms, and you don’t figure out why the alarm is firing when it shouldn’t be, then it’s not a useful alarm anymore.

We worked on a project where we asked to get some alarm resolution. We got a lot of issues resolved, but couldn’t get them all resolved. In one case, there was a horn behind the driller in the driller’s cabin. After about two or three days, someone brought the electrical technician in and said, disable that thing. Because it would sound every time the water-tight door to the lower equipment room opened. Why have an alarm in that place, for that purpose? Why would the driller need to know that? No one had thought through the process.

Offshore:That sounds like requirements validation.

Shafer:It is. We do a lot of requirements validation. And the real key there is, do you have the requirements? In every drill floor, every rig – even if you decide to build five identical, cookie-cutter rigs, and it takes, say five years from starting the first to finishing the last – in that five years if you’re using Siemens programmable logic computers on your equipment, Siemens will have gone through two major changes in the hardware. They’re not the same. The software is different. The hardware itself is different. So, you have to look across the board at what’s happening to your systems as they evolve. These are things that the industry just wasn’t looking at.

Offshore: Are suppliers working with you?

Shafer:Yes. Now we’re helping the various equipment suppliers to integrate their products and processes so that they can communicate and coordinate more efficiently and effectively. Once we’ve worked with a vendor, we don’t get any pushback. They’re happy to work with us because they see the value of it. They just weren’t aware of it before. The economic buyer just wasn’t pushing for it. So it didn’t happen.

Offshore: It’s got to be a big task.

Shafer:Think about the complexities of integration of systems. When you get on a drill floor, the systems there that need to communicate with one another might include, Windows, Siemens PLCs, Allen-Bradley PLCs, and imbedded Linux operating systems, for example. Sometimes the engineers are trying all kinds of new things, and no one is asking will it really integrate with the automated mouse-hole they’re going to put in? Will it integrate with the subsea production system? The controllers?

One of the major things we’re talking about doing now – and one of the super majors is pushing very heavily for it – is dual-gradient drilling. It changes the game considerably. With dual-gradient drilling you’re going to put mud pumps and tanks on the ocean floor, and you’re going to have to manage a different differential. It takes an exponential change in the amount of signals and the amount of processing you’ve got.

That’s why it’s important to do the reviews up front and to ensure that you contractually specify that you’re going to do those reviews. You have make sure that contracts acknowledge your asset’s life cycle and the fact that you’re going to have review points and that you’re going to put a process in place. You need to manage the software like it’s just as important as the iron you’re putting in.

Offshore: The oil industry started with pig-iron and power. Software is relatively new.

Shafer:Yes, but that perspective is changing. Imagine that you’ve just gotten on a plane in Houston, and it’s the new Airbus and you’re going to fly on Air France back to Paris. You’re sitting up in business class, and all of a sudden a guy comes on board carrying a laptop – and he’s got a lot of tattoos and piercings and an orange Mohawk. And he walks into the cockpit and sits down. The door closes. Halfway through the flight he walks back through the cabin and you stop him and make conversation and ask what his job with the airline is. And he says, well, I’m the programmer for this airplane, and we wrote all the takeoff software, but we didn’t write any landing software. I’m writing the landing software now.

That’s what we have in some cases. The systems aren’t put together until they’re brought onboard the vessel while it’s in the shipyard. In South Korean, Singapore, or wherever they’re being built, that’s the first time that all the equipment has ever been put together.

Back to the DP system, integration is critical to that process. We work with everything from DP, to power, subsea, fire and gas. All the vessel management systems.

Offshore:For example?

Shafer:Take, for example, the software for steel catenary risers (SCRs). SCRs have strain gauges that constantly monitor the strains they experience, and you have to send the information onshore every so many minutes to show what the turning moment is, for example, and what else is happening to the SCR. You have to monitor all of that. At the same time, you’re getting instrumentation regarding a production system and you have to worry about the production flow, how much oil is coming up, how much gas is coming up, and that data goes to shore. Also, if you’re at a point where you’ve got multiple production platforms you have to have that data firewalled. If production goes down, the trading floor can’t know that production is down for some reason, because someone might use that as insider information in a trade. So all these pieces have special objectives, and the SCR has its own separate server, its own separate network, and it’s one more piece of the complexity that we’re describing.

Offshore: Do you work with the software providers?

Shafer:On a regular basis we send a questionnaire to the software suppliers’ quality assurance personnel, HSE personnel, and others, and we do a series of conference calls. This is all in review of internal documentation of their software. Then we go onsite for a week and actually talk to programmers, look at documentation, ask about their testing, ask about configuration management, backups and restores – all very basic questions about their software development. Then we write a report that goes to the vendor and our client. Then we go back and have a retrospective on what we found.

We’ve got a lot of experience in the semiconductor industry. And in a sense, a drillship is like a factory. It’s doing hazardous work, but it’s essentially functioning like a factory – and you should treat it like that, from the viewpoint that if you can get the equipment working together, you can improve productivity and safety. That’s our goal.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com