East Coast Australia, Indonesia facing gas supply shortages in years ahead

By Jeremy Beckman, Editor-Europe

Gas continues to be a premium commodity throughout the Asia-Pacific region. Some nations are more blessed in terms of natural resources on their doorsteps, but the incentives and administrative will to explore and develop can be variable.

Australia's declining exploration activity, delayed investments

In Australia, the east coast and southeastern states have become increasingly dependent on surplus gas produced at the Shell-operated Queensland LNG terminal on Curtis Island; coal seam gas produced by the ConocoPhillips-led Australia-Pacific LNG joint venture from the Bowen and Surat basins in southern Queensland.

There had been warnings of a gas shortfall during the present winter season due to fears over storage capacity and declining output from fields in the offshore/onshore Gippsland, Otway and Cooper basins, but this was alleviated in May when Australia-Pacific LNG signed two new supply agreements to cover East Coast needs. However, the situation could still worsen over the longer term with the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) predicting that demand for gas-fired power in the region will keep rising, with little signs of a buffer against unexpected high-demand events such as extreme weather.

Successive administrations in Australia have resisted calls to address the situation by opening up new areas offshore southeast Australia to exploration, in the assumption that renewable energy would cover the region’s future power needs. In March, New South Wales’ state government passed legislation banning petroleum and mineral exploration of the seabed out to 3 nautical miles from the coastline (the federal government controls waters beyond this point).

According to Daniel Toleman, research director of global LNG at consultancy Wood Mackenzie, market confidence in future domestic gas developments has been undermined by an increasingly complex policy environment resulting in declining exploration activity and delayed investments. These are “creating a cycle of underinvestment that threatens the long-term affordability and reliability of gas supply [to the East Coast],” he said. Wood Mackenzie’s analysis indicates that year-round shortages of gas in the region will become increasingly likely early in the 2030s.

For the incumbent Australian administration that won the country’s recent election, addressing the gas supply shortfall along the South East Gas market is a key priority, said Joshua Ngu, Wood Mackenzie's vice chairman, Asia-Pacific.

“Indigenous gas production from that area, most of which is currently from Victoria, is declining and could see a huge drop in 2030," he said. "Further exploration as well as the development of existing discovered resources, including Santos’ onshore Narrabri gas project [northwest of Sydney], is required to mitigate the extent of the supply decline.

“The present challenge in the South East Australia market for the near term remains the shortage of gas in the winter months. While this short-term requirement can potentially be met through storage and demand management to meet very acute shortage, new gas supply from offshore fields and/or imports will be required to meet the structure supply decline from the 2030s.”

Offshore the southeastern states, exploration of new fields at present is only permitted for companies holding licenses to explore and produce from existing acreage.

“It is not certain when another licensing round will be held,” Ngu added. “There are a few under-explored plays in the offshore, for example the Great Australian Bight offshore South Australia (which we don’t expect we’ll see drilled for environmental reasons), the deepwater Gippsland Basin, and the Sorrel Basin outboard of the Otway Basin. But there isn’t a huge appetite for offshore exploration in southeastern Australia at the moment; it’s difficult and expensive to manage the regulatory burden and the threat of environmental lawfare. The current anti-seismic stance in the Future Gas Strategy further hampers the appetite and ability to explore.”

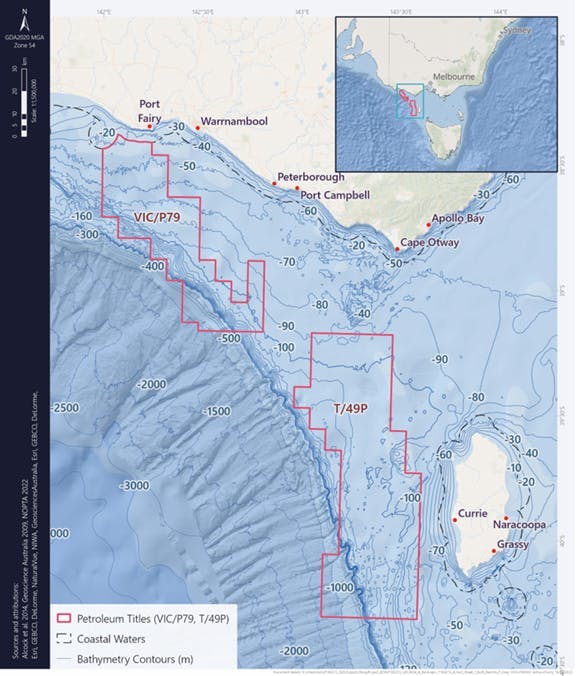

The Otway Basin extends offshore and onshore about 500 km (310 miles) from Cape Jaffa in South Australia to Victoria and northwest Tasmania. A consortium of E&P companies has hired the Transocean Equinox semisub for a multi-well campaign that was due to start in the current quarter, comprising a mix of exploration wells targeting gas and P&A of existing gas producers. ConocoPhillips Australia is operator of two exploration permits in the basin that are set to see action, VIC/P79, 19 km offshore Victoria, and T/49P 28 km from King Island, Tasmania. The other partners are 3D Energi and Korea National Oil Corp., the latter pending completion of a farm-in announced earlier this year.

According to 3D Energi, up to six exploration wells could be drilled in two phases: two firm wells are planned this year in Phase 1, followed by up to four optional wells next year under Phase 2. The company’s most recent update noted that three locations had been identified for the Phase 1 drilling program in the offshore Victoria permit. Beach Energy, an established offshore gas producer in the Otway Basin, expects Transocean Equinox to start P&A in the fourth quarter of its Geographe 1 and Thylacine 1 wells followed by the Hercules 1 exploratory well, a gas prospect in the Waarre C reservoir. A commercial discovery here could be connected to the nearshore Otway gas plant that produces supplies for the Victorian market from nearby offshore gas fields.

According to Ngu, the planned targets are not huge-volume prospects—potentially 50 to 250 Bcf—but any finds “will be very welcomed in the southern states' gas market.” ConocoPhillips was appointed operator of its permits relatively recently. “As the company doesn’t currently have any infrastructure in the area, it’s not certain if they will try to use third party or potentially build their own,” Ngu added.

New gas production and infrastructure offshore Australia

In February, Esso Australia Resources and partners Mitsui and Woodside Energy (Bass Strait) took FID on a near-$200 million investment in the Kipper 1B project, designed to expand gas production capacity at the Kipper Field in the offshore Gippsland Basin. The VALARIS 107 jackup has been contracted to drill and install one new well at the Kipper Field, with accompanying upgrades to the West Tuna platform. The new facilities should be operational ahead of Australia’s 2026 winter season. In 2024, the partnership also completed the installation of new compression facilities at the West Tuna platform as part of the Kipper Compression project. Esso Australia added that it was working on other projects to sustain gas production to the East Coast market from its Gippsland operations into the 2030s.

One of these is Turrum Phase 3. According to Woodside, innovative use of new 3D seismic data in the basin to visualize the subsurface led to the identification of new drilling targets. Four to five new gas wells will be drilled this year as part of Turrum Phase 3 to maximize development of the Turrum Field reservoirs. Combined with Kipper 1B, Turrum Phase 3 is expected to add more than 100 PJ (Woodside equity interest) to the southeastern Australian domestic gas market, with an estimated price tag of more than $500 million for both projects.

David Berman, ExxonMobil Australia commercial director, speaking at the 2025 Australia Domestic Gas Outlook Conference in Sydney earlier this year, said sustaining gas supplies from the Gippsland Basin had only been possible due to the company and its joint venture partners investing $8 billion over the past 20 years to develop new domestic gas supply.

“The ACCC is right when it says new gas production and infrastructure is not being brought online fast enough," Berman said. "But despite a consensus on the problem and its causes, there is less alignment on how to reclaim the investment certainty that is required to secure the capital to produce the energy Australia needs...

“There are many barriers to project development in Australia, such as duplicative state and federal regulations, which result in complex, uncertain and lengthy project approval processes. Which brings me to policy stability… It is a fact that the investment in Turrum Phase 3 relies on the policy stability provided by the Gas Market Code exemption framework and delivery remains dependent on efficient and predictable regulatory approvals. In the last month, however, we have seen multiple proposals to intervene further in the market, whether that is to expand the non-emergency powers of the Australian Energy Market Operator or an east coast domestic gas reservation. We urgently need to get back on a path that leaves behind the uncertainty resulting from repeated government interventions…"

He continued, "That is why the mandated review of the Gas Market Code in 2025 is the opportunity for government and regulators to ensure these and future gas investments continue to move forward by making a clear and durable commitment to long-term market policy stability. Stability that will provide the certainty producers need to invest and the confidence buyers require to contract long-term supply.”

Demand for FSRUs

In a report published earlier this year, Wood Mackenzie's Toleman mentioned importing LNG via floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) as another potential measure that could ease East Coast gas shortages. He warned, however, that surging global demand for FSRUs has made the available vessels costly.

"The [Australian] government may need to underwrite the commercial risk of such infrastructure," he said. "Moreover, importing LNG would expose Australia to volatile global prices.”

Nevertheless, a few regas terminals have been proposed, Ngu added, of which four are currently being progressed: Port Kembla FSRU in New South Wales, Avalon and Viva LNG in Victoria, and the Outer Harbour FSRU in Adelaide.

“Port Kembla FSRU is the most advanced with an initial startup of 2026 that has now been pushed into 2027,” he said.

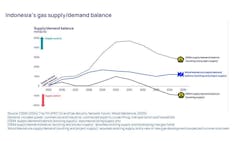

Indonesia's deepwater gas riches

Indonesia has an abundance of undeveloped deepwater gas resources, with the Abadi, Geng North, Layaran and Tangkulo fields containing more than 35 Tcf combined, according to Wood Mackenzie. On top of that, unexplored parts of the North and South Sumatra basins and the Northeast Java Basin could hold more than 30 Bboe, based on estimates by the Indonesia Exploration Forum. However, a recent Wood Mackenzie report warned that the country may still face domestic gas shortfalls by 2033 due to declining production, without development of new fields. The government has set a target of 12 Bcf/d by 2030, but the consultants currently estimates supply to be about 7 Bcf/d in the 2030s based on existing projects in the pipeline. They recommend implementation of new incentives to support both the discovery and fast-track development of new gas resources, while at the same time maintaining Indonesia’s position as a major exporter of LNG.

“Developing new gas fields requires time and investment, particularly for larger discoveries far from existing infrastructure and demand centers,” said Andrew Harwood, vice president Corporate Research, Upstream & Carbon Management, at Wood Mackenzie.

“A business-friendly environment can accelerate the timeline for bringing new gas supply onstream,” he said, via measures such as:

- Regulatory assurance for contract sanctity that honors the terms of the investment case at the point of FID;

- Adaptive gas pricing that incentivizes investment on a project-by-project basis, taking into account buyers’ requirements and the risks and commitments assumed by producers; and

- Flexibility for developers under which buyers honor long-term take-or-pay agreements, but with developers allowed to sell their gas to other parties in Indonesia or internationally should buyers be unable to accept offtake volumes.

Following last year’s presidential election in Indonesia, won by Prabowo Subianto of the ruling Gerindra party, the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (MEMR) did alter policy objectives, with a new emphasis on domestic energy security. This had an immediate impact on the Conrad Asia-operated 413-Bcf Mako gasfield development in the West Natuna Sea. Conrad had negotiated two gas sales agreements (GSAs) with Sembcorp Gas of Singapore and PT Perusahaan Gas Negara for the domestic portion of the gas produced. After the election, however, MEMR directed that all Mako’s gas had to be sold domestically in Indonesia, leading to both GSAs being terminated.

In May of this year, after obtaining ministerial approvals, Conrad agreed on a new binding GSA with a subsidiary of Indonesian state power utility PLN Persero for all future production from Mako, which the company expected to sign within a few weeks. Conrad noted how quickly the new GSA was negotiated and agreed to, including linking Mako’s gas price to the Indonesian crude price instead of the fixed domestic offtake price normally mandated for domestic sales. The arrangement was designed to ensure the company would not be disadvantaged compared to the pricing it had previously agreed under the canceled GSAs.

Wood Mackenzie's Ngu said, “For all gas developments in Indonesia, there is a gas allocation process, and the government will balance the domestic needs and decide whether export is allowed. As of 2025, there have been gas shortages in Java Island, which has also necessitated uncontracted LNG cargos to be sold domestically. The government is taking a much a closer look at domestic supply demand balance. There is no official regulation that there is an export ban, but it’s clear that domestic markets will be prioritized. A clear gas policy and direction from government will be required to provide confidence for investors.”

This appears to be the case for the Medco Energi-led joint venture in the Sampang PSC offshore East Java/Madura Island. In its latest results update, partner Cue Energy mentioned Medco’s continuing difficulties persuading the Indonesian government to amend the production sharing contract (PSC) terms to incentivize a final investment decision on the offshore Paus Buru gas development (a single-subsea wellhead development exporting gas to the Oyong infrastructure).

“Amending PSC terms for existing projects has always been difficult for the government,” Ngu said. “These amendments are typically provided after existing contracts have expired. Many other companies with both small and large offshore projects are looking to extend field lives and unlock more technically challenging gas resources via amendments to PSC terms.”

More investment in CCS/CCUS projects

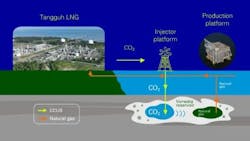

At the upper end of the development scale, one of the largest new investments announced last year was the $7 billion Tangguh UCC project onshore and offshore West Papua, Indonesia. The initial Tangguh LNG development harnessed gas from six fields in Bintuni Bay, with a third liquefaction train added in 2023. The new project, which will develop an additional 3 Tcf of gas, involves a combination of production from the offshore Ubadari gas field, enhanced gas recovery through CCUS, onshore compression and expansion of the existing Tangguh LNG infrastructure. The new facilities will include three injection wells, an offshore injection platform, an offshore CO2 pipeline, and onshore facilities to remove, process and compress CO2. bp is the operator, in partnership with MI Berau, CNOOC, Nippon Oil, KG Berau Petroleum, KG Wiriagar Petroleum and Indonesia Natural Gas Resources.

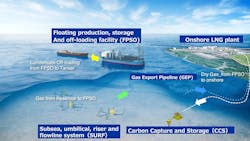

Another planned LNG/carbon capture and storage (CCS) project concerns the INPEX-operated Abadi Field, which was discovered in 2000 in the deepwater Masela Block in the Arafura Sea offshore eastern Indonesia. INPEX received approval from the government in 2019 for its original development plan to produce 9.5 MMt/year of LNG. But this was later revised to incorporate CCS, with Pertamina and Petronas joining the project in October 2023, two months prior to the government approving the updated proposal. INPEX recently said that, following further studies and preparations including environmental permits and project financing, the partners are aiming to launch the development in 2027. Ngu said the approved plan of development is expected to recover 11.5 Tcf, and total estimated gas in place is 21 Tcf.

“From a regulatory perspective, development of large-scale LNG and non-LNG projects in Indonesia does not necessitate the incorporation of CCS,” Ngu said. “However, it is both the government’s ambition and the companies’ own requirements to reduce carbon emissions and make sure that their development is as low-carbon as possible. This is especially true for new developments that have a high CO2 content. Tangguh CCUS required certain approvals from the government; one of the key considerations for the partners was understood to be that the capital investment for CCUS should be cost-recoverable. For many companies, CCS/CCUS is increasingly considered as a license to operate and carbon emissions/intensity of any project is a key part of their internal investment approval and capital allocation process.

“As for Abadi LNG, the project went through several iterations. The initial contention for the development of the project was whether to go for a floating or an onshore solution. The latter would cost more given the distance of the discovery from shore, but the government had pushed for an onshore solution to enable local job creation. The latest plan of development, which includes CCUS, has been approved, and INPEX is currently performing FEED. This is a mega-project, and a key challenge will be the cost. We’ve seen recent cost estimates come in higher than expected for other projects in the region, including TotalEnergies’ Papua LNG in Papua New Guinea. INPEX’s CEO has publicly highlighted the need for more attractive fiscal terms to enable the development of the project. Petronas and Pertamina coming on board helps with the development of the project by sharing the capital risk and by bringing complementary technical capabilities. All three companies have experience developing LNG projects.”

Further development of offshore Indonesia gas resources

Another emerging gas province in Indonesian waters is in the Andaman Sea offshore northern Sumatra, where Mubadala Energy and partner Harbour Energy made back-to-back discoveries in 2023-24 with the Layaran-1 and Tangkulo-1 wells in up to 1,200 m (3,937 ft) of water. At the time, Wood Mackenzie assessed the potential resource discovered at 11 Tcf. According to Ngu, further near-field exploration in the Andaman Sea is planned around the earlier Timpan gas discovery, but otherwise no other exploration appears to be lined up in the area for the time being.

“Harbour has just acquired the Central Andaman Block, but that needs to be worked up for prospects and leads. For the existing discoveries, the development plan will likely be phased, with Tangkulo produced first to supply the domestic market," he said. “Monetization of the Andaman Sea’s hydrocarbons is the key challenge for discoveries in that area. There is some domestic demand that can take some of the gas. However, the full monetization will require the gas to be exported from the region. The immediate option is to wait for the completion of the Dumai Senkai pipeline that connects North and South Sumatra, with further pipeline connections to Java and Singapore. Alternatively, the onshore Arun gas field in northern Sumatra [which was converted to an LNG import terminal in 2014] could be reconverted into a LNG liquefaction terminal, but this would be expensive. Looking further ahead, a gas export pipeline to Malaysia/Thailand could potentially be considered as a future option if even more discoveries are made in the Andaman Sea."

He continued, “The Indonesian government is keen to develop more of its discovered offshore gas resources to boost domestic production. For example, the potential for monetizing the giant Natuna D Alpha Field in the East Natuna Sea, which was discovered in the 1970s and which has a 70% CO2 content, is still being discussed and considered by the government. We have seen some easing of fiscal terms in certain expiring PSCs in mature areas, but we have not seen the new improved fiscal terms being offered to existing discovered but undeveloped fields.”

Another recent development that could unlock future offshore gas projects is Eni and Petronas’ joint venture in Indonesia and Malaysia, the goal of which is to create a self-funded independent business with 3 Bboe of reserves and a combined equity production target of 500,000 boe/d.

“While the details have not been revealed, we expect Petronas’ assets in Indonesia, including Abadi, to be considered as part of this arrangement, while Eni will likely inject its offshore E&P interests in the Kutei Basin," he added. "Both companies hold exploration assets in Indonesia and Malaysia, the majority of which are near-field exploration opportunities.".

He concluded, “As for future frontier exploration for new gas provinces in Indonesia, some of the areas we are keeping an eye out for include Sulawesi, West Papua and East Java—here, there is potential for new exploration activities on acreage held by bp or POSCO. Similarly, we anticipate future drilling in West Papua from the like of Petronas and EnQuest, which have both acquired acreage in that area.”

This article was last updated 9:42 a.m. CT on July 11, 2025.

About the Author

Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

Jeremy Beckman has been Editor Europe, Offshore since 1992. Prior to joining Offshore he was a freelance journalist for eight years, working for a variety of electronics, computing and scientific journals in the UK. He regularly writes news columns on trends and events both in the NW Europe offshore region and globally. He also writes features on developments and technology in exploration and production.