David PaganieHouston

Globally there are thousands of offshore wells and related infrastructure that have reached the end of their useful life. Some areas such as the US Gulf of Mexico and UK and Norwegian North Sea have government regulations that require the removal of the infrastructure in compliance with set guidelines.

In other areas such as Asia/Pacific, the regulatory environment and supply chain for decommissioning will need to improve to support upcoming activity. Wood Mackenzie estimates that nearly 2,600 platforms and 35,000 wells in the region may need to be decommissioned in the years ahead, with a total bill of over $100 billion. Some analysts expect the size of the decommissioning market globally to exceed $200 billion.

Inside this issue, Offshore assesses government and industry capabilities to handle the expected growth in decommissioning requirements.

For operators, decommissioning is about regulatory compliance and meeting shareholder expectations. There is no financial incentive to remove and clear obsolete infrastructure. Thus, estimating and controlling the cost of the endeavor is critical.

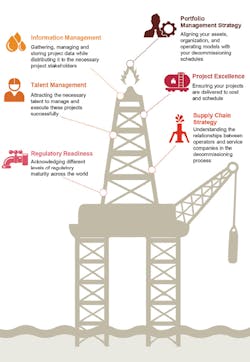

The six key issues critical to decommissioning success.(Image courtesy PwC)

There are very few historical benchmarks for the cost, schedule, and scope of decommissioning projects, due to the infancy and size of the market, says Anthony Caletka and Casey Carringer with PwC, on page 26 inside this issue. The authors suggest that failure to accurately estimate the timeline and costs for a decommissioning project poses significant risks to organizations.

One approach to minimize costs and risk is to tailor a decommissioning program to comply with government regulations, the authors explain. Governments are evolving to meet the growing requirements, and beginning to hold operators more accountable. “Governments are beginning to adopt best management practices, quantify, and interpret presumed decommissioning exposures through probabilistic cost estimates, and collaborate with industry to determine viable decommissioning alternatives (i.e. the Rigs-to-Reef program in the GoM gaining international notoriety) with the dual mandates to safeguard their environmental assets and taxpayers’ dollars.”

Digital technologies may also help reduce risk. “The use of ‘digital twin’ technology, including drones and Lidar (Light Detection and Ranging) may be required to digitize existing infrastructure, to properly reverse engineer and scope the decommissioning sequence and timing to ensure that a project complies with safety, environmental, and regulatory constraints,” the authors suggest.

Meanwhile, the supply chain is adapting to the growing market. “Several operators have said they would like to see partnerships in the services industry that can provide consistent turnkey solutions but still allow them to maintain oversight of the operation,” the authors observe. Turnkey decommissioning is a strategic partnership between EPCI and OFS companies to create holistic “one-stop shop” services. The EPCI companies provide the jacket, topsides, and subsea removal services; and the OFS companies perform the P&A work on the well and subsea infrastructure.

This emerging market is a bright spot for the oilfield services sector. It should provide opportunities to reengage some personnel and equipment while the pipeline of new exploration plans and field development projects builds back up.

To respond to articles in Offshore, or to offer articles for publication, contact the editor by email ([email protected]).