Contributing Editor

The international oil and gas industry is expected to invest $44.5 billion on Floating Production Systems (FPS) in 2010-2015, according to industry projections. Of the 200 FPS planned for construction in this timeframe, sixty-seven are expected to be installed in deepwater. The ultra-deepwater segment would have 30 FPS units installed in water depth of more than 1,500 m (4,920 ft).

“Prospects are bright but challenges are plenty,” said Christopher M. Barton, McDermott Asia Pacific Pte. Ltd.’s vice president for Business Acquisition in the region.

Technology is available but it would be a challenging task, as the global contracting industry is limited in its ability in many ways, Barton said in a recent interview withOffshore in Singapore.

Barton has called on the oil and gas industry to pre-plan all high-cost developments, saying “solid execution strategy is always needed” in terms of being the prudent or smart thing operators should do. Pre-planning means performing activities such as the concept study and front end engineering design (FEED) phases of a project that deliver significant benefit-to-cost results. These activities ensure solid strategies are created for the execute or EPCI (engineer, procure, construct, and install) phase, allowing projects to proceed according to plan and to achieve budget, schedule, and performance goals. With minimal or poor pre-planning, projects tend to move prematurely into the execute phase, putting all goals at risk, Barton noted. “Projects cannot ‘get it right’ by starting with a poorly defined execution strategy.”

Following is a conversation betweenOffshore and Barton in which he detailed the challenges facing the offshore industry.

Offshore: Why does the industry always seem to be short of EPCI contractors?

Barton: The dearth of deepwater contractors stems from a combination of factors. These include:

- A continued shortage of personnel with the expertise specific to the design of these facilities and related installation engineering

- The cost of assembling and maintaining the expertise during quiet periods or industry downturns is expensive, requiring significant corporate commitment and deep pockets

- An active R&D program is required, which further adds to the cost of participating in this market

- Bidding these projects is expensive, often millions of dollars per bid, whether successful or not

- Fabrication of deepwater facilities requires large shipyards and topside fabrication yards. Many that are large enough are not interested in taking on the engineering and installation risks associated with deepwater projects and, therefore, limit their role to fabrication

- The marine assets necessary to install deepwater projects are few and far between. They are expensive to build and maintain, and particularly to own during slow times in the business.

The bottom line is that a deepwater contractor must devote substantial ongoing investment in expertise and hard assets. Thus, there are cost barriers. Deepwater projects are also high risk, and operators are reluctant to award work to new players without track records or financial strength to assume these risks.

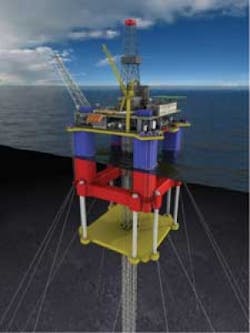

We also need to be right for technology selection – compliant tower, tension leg platform, semi-floating production systems, floating production storage of offloading units, deep draft semis, truss spars, and subsea facilities. But project owners have to understand the technologies. The technology solution is a key driver of the construction strategy. However, constructability and install-ability often drive the selection process.

Offshore: How challenging would it be to fit the new technologies into developments, and what exactly should the project owners/investors do?

Barton: Developing and proving new deepwater technologies is time consuming and expensive, often taking 10 years to gain acceptance and bring to market. Cost, benefit, and risk determine user acceptance of new technologies. Application of new, or old, technology to a new project is properly determined at the concept study (conception selection) phase, during which a large number of reservoir and site-specific factors are considered in selecting the technologies that are best suited for the application. Over the longer term, operators are best served by working with contractors in JIPs (joint industry projects) or funding technology-specific studies.

Offshore: Contractors also face limitations. There are a few “centers of technical excellence” and a few local hull fabrication yards. Limited numbers of deepwater installation vessels add to the challenges of executing the projects. How can this situation be improved?

Barton: Thirty years ago there were few “centers of excellence” in the conventional offshore project market; now there are many. Engineering for the shallow-water market has actually become a commodity business. The same evolution will probably not occur in the deepwater market. Constraints include the limited number of deepwater projects, greater degree of technical proficiency required, and cost barriers to entering the EPCI phase of the business. Yet, “centers of excellence” will grow in number, fueled by legislated local content requirements; some governments’ focused investment programs; and geographic expansion among existing deepwater contractors.

Offshore: The “first-of-a-kind” (FOAK) design is another challenge for both the contractors executing the project, and the investor/owner sponsoring its development. Are these types of projects growing in number? There hardly seems to be any technology breakthrough. Are these FOAKs really making a difference?

Barton: FOAKs are happening constantly in the context that each deepwater project provides multiple opportunities for a new design, new installation procedure, building “the biggest yet” or installing it in the “deepest waters yet.” These FOAKs provide one or more benefits such as reducing costs, lowering project risks, shortening schedule, increasing facility reliability, enabling economic development of a reservoir, and improving safety.

Offshore: Can you elaborate on the need to develop construction strategy early on in project development, in order to efficiently and effectively manage and mitigate risks?

Barton: The construction strategy should be finalized during the FEED phase of a project and should start by weighing different construction approaches during the concept study phase. This ensures that concept selection is performed in light of the restraints related to building and installing the design. Cost, schedule, and risk penalties result if a chosen design proves difficult to build and install, no matter how well the facility might perform once installed. Commencing the execute phase of a project without a well thought-out construction strategy leads to missteps, delays, and risks that were not sufficiently examined and planned for during the FEED phase.

With proprietary designs in TLP, spar and semisubmersible structures, FloaTEC LLC focuses on the extendable draft semisubmersible (E-Semi) concept. FloaTEC, a joint venture company between a McDermott subsidiary and Keppel FELS, also conducts research and development.

Offshore: How can the industry manage the long supply distances in an environment of speculative prices and ever-increasing material costs?

Barton: “Long supply line distances” refers to the fact that many installation sites for large deepwater projects are far removed from traditional shore-based resources. Marine spreads and hook-up and commissioning crews need to be more self-sufficient once on site – planning for longer waits for parts, tools, and people that are sourced from shore. With regard to speculative prices and increasing material costs, suffice it to say that this risk is best born by operators, and contract terms should reflect this.

Offshore: Is it possible to change the thinking of policy makers who want to leverage maximum value from mega-projects? As you know, local governments often call for technology transfer, and require the use of local products and businesses in these high-cost projects.

Barton: Accommodating local content requirements must be considered as part of defining the execution strategy. Local content requirements may add risk and cost to a project if, for example, local engineering firms, fabrication yards, or marine contractors do not yet have the degree of experience or tools needed to perform on a world-class basis. However, application of local content requirements is the prerogative of local authorities and/or operators, whose priorities are based on their own longer-term interests.

Offshore: Should feasibility studies be shortened, since a longer feasibility study may be outdated in a fast-changing market environment?

Barton: Deepwater projects are typically complicated, expensive, and carry greater risks than any other project of similar value. Major oil companies often spend a year performing concept studies, followed by another year of FEED. In the context that the field will produce for 20 to 30 years, a few more months spent towards ensuring project goals are met is time well-spent. Another reality is that the oil and gas market is not fast-paced. It changes slowly relative to the petrochemical or consumer market. The product is marketed globally as a commodity and production life is measured in decades. The product itself (oil or gas) has not changed in a century. Time to market is not critical and a project’s net present value is relatively insensitive to it. Even an offshore facility supplying an LNG plant is typically immune because the LNG plant is on the schedule’s critical path, not the offshore facility.

An industry veteran with 30 year’s experience in the upstream oil and gas industry, Barton has held senior leadership positions with FloaTEC, ABB, and Technip. Since starting his career as a field engineer with J. Ray McDermott in Singapore in 1980, he has worked in a range of roles within operations, engineering, and fabrication, on a number of projects throughout the world, including the Atlantic, Asia Pacific, and Middle East.

In his role as VP, Business Acquisition-Asia Pacific for McDermott, Barton has regional responsibility for business development, proposals, sales and marketing, and communications. His experience includes project engineering, project management, construction site supervision, offshore operations, and field development work, including platform fabrication and offshore installation.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com