Latin America enters new era of competition and urgency

Bruno Triani Belchior, Leandro Duarte Alves

Tauil & Chequer Advogados

Host countries working to offer better terms, transparency

The oil and gas industry has long been characterized by the need to advance rapidly and maximize opportunities. International oil companies closely watch global activities, searching for different types of projects, and it is incumbent on host countries to attract international investors.

Latin America is not different, and while the relevant host countries’ regulatory authorities are competing for oil and gas investments, each country must address the factors that in one way or another have diminished the competitiveness of its oil and gas industry.

In the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, in which the supremacy of oil and gas will slowly decrease over time, oil-producing countries need to maximize the value of their reserves. Despite constant time pressures, oil companies typically conduct comprehensive analyses of the political risks and the regulatory framework of a target country, focusing on how those matters may impact the economics of potential projects.

In this race, Mexico seems to have gained a head start through the reform of its energy sector with a view to drawing more investment.

Mexico’s energy reform

One may argue that the race began in December 2013, when a comprehensive energy reform bill formally became law in Mexico. A few months later (August 2014), nine new laws and amendments to existing laws implemented the December 2013 constitutional energy reform and established a new legal framework for Mexico’s energy industry.

In a major shift from previous policies, Mexico remarkably allowed private companies to invest in its oil and gas sector. It is worth noting that, prior to the reform, Mexico had wisely paid attention to its peers (competitors) in Latin America and tried to meet the demands of the market. Undoubtedly, Mexico learned a great deal from Brazil’s experience, especially its mistakes.

During that period, the Brazilian Petroleum Agency (ANP) was disappointed with the outcome of the 1st presalt bid round under the production-sharing regime. Due to the lack of investor-friendly rules, including the exclusive right of Petrobras as operator, only one consortium submitted a bid. Even that bid, in respect of the highly promising Libra block, resulted in the minimum profit oil split (41,65%) to the government. Learning from that negative experience and in light of Mexico’s reform by comparison, Brazil felt compelled to re-examine its regulatory approach in order to re-join the race.

Brazilian reaction

Following a period of five years (2008 to 2013) with no offshore bid rounds – primarily because of protracted studies and geophysical speculation regarding the presalt area – it was critical for Brazil to create a predictable, attractive and competitive market, as the industry was being impacted negatively due to the inactivity.

Starting in mid-2016, Brazil made a significant shift in its approach to the oil and gas sector. Since then the country has been promoting a further opening of its oil industry – featuring reforms arguably more significant than those of the late 1990s, when the concession regime was introduced as part of a general opening to foreign investment.

This new opening of the market comprises a variety of opportunities including new bid rounds, important changes to the local content regulation, permanent offer of areas, and a specific regulation on Petrobras’ divestment process.

Shell won nine of 19 blocks awarded in Mexico’s bid round 2.4 in February. (Courtesy Royal Dutch Shell)

Recent bid rounds

After a regulatory adjustment that allowed other companies to assume the operator role in the presalt area, the ANP launched the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th bid rounds. As a result of the new flexibility, Shell and Equinor became presalt operators. From a government take perspective, the federal government received BRL 9.3 billion ($2.4 billon) as a signature bonus and nine areas were awarded in total.

In parallel to the presalt bid rounds, the ANP has recently organized the 14th and the 15th bid rounds under the concession regime. As a result of releasing a schedule of bid rounds in advance, offering more interesting areas, and creating a more flexible local content policy (as explained below), the outcome was considerably stronger and more lucrative.

Local content regulations

In April 2017, the Brazilian federal government decided that local content would no longer constitute a specific component of the bidding process. Instead, offers would be composed of only signature bonus (80%) and minimum exploratory program (20%). In addition, the local content requirements were reduced by 50% on average for these bidding rounds.

Although the above changes were significant, unrealistic local content requirements from previous bid rounds, especially from the 7th (held in 2005) to 13th (held in 2015) bid rounds needed to be addressed. In this regard, and as a result of discussions between the Brazilian government and oil companies, the ANP published Resolution No. 726/2018 (Resolution), which provided the concessionaries with the option to express to the ANP its interest in amending the local content requirements of the relevant contracts. According to the Resolution, by agreement of all signatories, the local content clauses under the production-sharing agreements and the transfer of rights agreement may also be amended.

For those companies that do not opt for the amendment process, the Resolution stated that an exemption (waiver) may be authorized in the event of (i) the absence of a Brazilian supplier, (ii) offers from Brazilian suppliers with expensive prices compared to the prices of foreign suppliers of similar goods/services, (iii) offers from Brazilian suppliers with excessively long delivery time compared to the delivery times of foreign suppliers of similar goods/services and (iv) the absence of a new technology in Brazil.

In short, Resolution 726/2018, along with other factors, may well encourage future investments. Indeed it is expected that 39 new platforms will be operating and roughly $250 billion dollars (BRL $845 billion) will be invested in development and production by 2027.

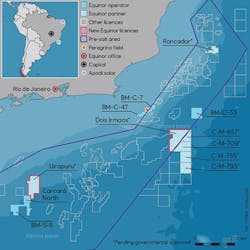

Equinor recently won stakes in the Uirapuru and Dois Irmãos blocks in Brazil’s 4th presalt bid round. (Courtesy Equinor)

Permanent offer of areas

In addition to the local content and other changes, in November 2017 the ANP approved the process of permanent offer of areas, with the purpose of allowing, through a differentiated system, the development of relinquished fields (or fields in the process of being relinquished) and exploratory blocks that have not been awarded (or relinquished) during past bid rounds.

The innovating factor of this initiative is that companies of different sizes will be able to participate in the assessment and selection process of the areas to be offered in the next bid rounds, with the exception of fields or blocks in the presalt area or other strategic areas.

In April 2018, the ANP published the first draft tender protocol concerning the permanent offer, establishing the rules for this new contractual regime and the technical and economic parameters of 884 blocks and 14 areas with marginal accumulation.

Regarding the bid evaluation criteria, it is worth mentioning that for blocks with exploration risks, the signature bonus and the minimum exploratory program will be the determining award criteria. For areas with marginal accumulations, the signature bonus will be the sole criterion.

The ANP has announced that the next round of permanent offer (also called the second cycle) will be launched by the end of 2018 and will encompass 1,039 blocks from 20 onshore and offshore sedimentary basins.

Petrobras’ divestment process

Brazil has also learned over time that to unleash future investments the market requires not only innovations, but also legal certainty. Addressing this point, in April 2018 the federal government enacted Decree No. 9.355/2018 (Decree), establishing a special procedure for assignment of rights regarding exploration, development and production of petroleum, natural gas and other fluid hydrocarbons by Petrobras.

As was the case with the Brazilian privatization program in the 1990s and all bid rounds, the industry expected that certain Brazilian unions would challenge Petrobras’ divestment plan in court. However, all players involved were confident that the superior courts would allow successful implementation of the divestment plan by overruling unfavorable lower court decisions.

The main objectives of the Decree include: establishing impersonality in the management of Petrobras’ exploration and production portfolio; ensuring legal certainty of the assignment procedures [to both Petrobras and relevant investors]; and ensuring the quality and integrity of the decision-making process that determines the assignment of rights.

The Decree lists the cases in which the competitive process of the assignment procedure will not be applied, which are: (i) in the formation or modification of partnerships or consortia, when the choice for a partner is connected to specific characteristics and to defined/specific business opportunities; (ii) when it is justified to not carry out a free competition procedure as provided for in the Decree; and (iii) in the case of right to withdraw, resulting from partnership agreements.

Country-specific challenges

For other Latin American countries, the competition for foreign investment involves improvement of the geological data. For example, Uruguay’s 3rd bid round under the production-sharing regime, held in April 2018, was declared void by the Uruguayan National Oil Co. (ANCAP), since no offer for the 17 offshore areas was presented. While two companies (Tullow Oil and Azilat) submitted the qualifying documentation, they ultimately did not participate. This result may demonstrate the declining interest of companies in these blocks due to the geological risk involved. It is worth noting that the winning bidders of the previous rounds (Round 2009 and Round II – held in 2009 and 2011, respectively) have not yet found significant reserves.

The future may create synergies among the countries in Latin America. As happened in the late 1990s, when Argentina provided Chile with natural gas, Mauricio Macri (President of Argentina) and Sebastián Piñera (President of Chile) are currently planning on resuming this arrangement. The main reason for this is the expected growth concerning the activities of Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale play. Since this huge reservoir rests far from Buenos Aires (the demand center), exportation to Chile is an attractive option.

To counter the negative investor reaction to the expropriation of Repsol oil subsidiary YPF in 2012, Argentina published, on Oct. 31, 2014, the New Hydrocarbons Law, with the purpose of attracting investments and addressing important topics such as taxation, royalties and bidding process. Recently, during a conference in Houston in May 2018, the Minister of Mines and Energy Juan J. Aranguren said: “Our goal is to generate the conditions to make the investors regain trust in Argentina, and encourage them to pass from pilot phase to the development phase of their projects in Vaca Muerta.”

In addition to the onshore activities, the Argentine Secretariat of Hydrocarbon Resources of the Ministry of Energy and Mining will call for bids to award exploration permits regarding offshore areas in July 2018 (Offshore Round 1), in order to receive bids in November 2018. This initiative demonstrates that the government is looking beyond the unconventional exploration potential.

Colombia is another country that is currently developing strategies to promote its oil and gas sector. The country is organizing its first bid round after a four-year pause. This bid round encompasses 15 onshore blocks located in Sinu-San Jacinto basin and will be held under the conditions established in the new regulation (Acuerdo No. 02) issued by the National Hydrocarbons Agency in May 2017. Moreover, similar to Brazil, Colombia also intends to initiate its own permanent offer system, which will include onshore and offshore areas.

Conclusion

As indicated above, the oil and gas producing countries of Latin America face many challenges to remain competitive with the US and other robust producers. Fortunately, the above-described governmental innovations and reforms are cultivating a revived sense of competitiveness in the race to attract foreign investment.

Ultimately, the international oil companies have a broad range of opportunities and options when it comes to major investment. Latin American oil producers have taken significant steps to enhance the attractiveness of their hydrocarbons regimes. Hopefully the significant progress of recent years will not be thwarted by possible political short sightedness in the wake of the elections to come. •