UK North Sea E&P facing potential turning point or tipping point

Key Highlights

- The UK North Sea's production is declining faster than predicted, with no new field developments approved this year, risking economic and employment impacts.

- The Energy Profits Levy has contributed to a 78% tax rate, discouraging investment and causing job losses, with the industry lobbying for a more stable, profit-based tax system.

- The industry estimates suggest that without fiscal reform, production could fall by 40% in five years, and infrastructure hubs may reduce from 90 to just four by 2040, impacting supply chain and regional economies.

- Exploration drilling faces delays due to regulatory and fiscal uncertainties, with only a few drill-ready prospects, risking a shift to unmanaged decline unless policy changes occur.

- Despite challenges, mergers and new field projects continue, and some companies are advancing development plans, supported by higher gas prices and strategic asset management.

By Jeremy Beckman, Editor, Europe

North Sea investors will be hoping for positive outcomes to the UK government’s review of the industry’s future. The findings from the oil and gas licensing and fiscal consultations, due to be published shortly, could make or break Britain’s E&P sector, which appears at present to be in a state of unmanaged decline, according to one analyst.

Production is falling faster than predicted with no new field development projects approved by the government this year. Other projects in an advanced state of construction still face uncertain outcomes due to challenges by environmental pressure groups, which the government has not opposed. No exploration wells have been drilled this year either, for the first time since 1960. At the other end of the lifecycle, the backlog of plug and abandonment (P&A) work on decommissioned wells keeps growing.

The igniter of the current crisis was the Energy Profits Levy (EPL) introduced in May 2022 by the previous Conservative Administration at a time of high energy prices globally. The incoming Labour government increased the levy further last year, leading to an effective tax rate for the sector, including existing petroleum taxes, of 78%. At the same time, the EPL was extended through 2030.

Industry association Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) has since been lobbying for urgent reforms to sustain the industry. The pressure to preserve not just future production but jobs may pay off, with speculation that UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves might announce an early end to the levy in her annual budget statement at the end of November.

OEUK has recommended replacing the EPL with a new permanent, profit-based tax mechanism in 2026, which would provide greater long-term certainty for E&P companies deterred from investments by the constant tinkering of UK petroleum tax rates. The proposal, the association argues, could:

- Secure £41 billion ($53.6 bilion) of additional investment in UK energy projects by 2050;

- Support the creation of 23,000 additional jobs by 2030; and

- Deliver additional tax receipts of £12 billion ($15.68 billion) by 2050, through a more stable production outlook.

In this alternative scenario, the "windfall tax" would become a permanent profit-based mechanism that would only be activated when both oil and gas prices exceed a set threshold. The headline tax rate would fall from 78% to 40%—a big step for a government committed to clean energy targets—but the new mechanism, OEUK claims, would still ensure additional tax revenues when commodity prices are high.

Crucially, it would provide companies with greater predictability, a fairer investment environment and stronger incentives to reinvest in UK projects, which would unlock new developments, support jobs and deliver a more stable production outlook through to 2050, the association argues.

The analysis was published in OEUK’s recent report, "Impact of UKCS Fiscal Policy on UK Economic Growth," which stated that without reform of the present current fiscal regime, Britain’s North Sea oil and gas production would plunge by about 40% from current depressed levels within the next five years. So, although the EPL might provide a short-term boost to tax receipts of £6 billion ($7.84 billion), it might also hasten the North Sea’s decline, leading to wider economic damage.

OEUK estimates that the levy has already caused the loss of about 1,000 jobs per month in the industry, with 90% of domestic supply chain companies now addressing opportunities overseas to compensate for a lack of work in the UK North Sea. This is because the levy has stalled both existing offshore projects and progress on new field developments.

Even if net zero targets are achieved, Britain will still likely consume 10 Bboe to 15 Bboe of oil and gas between now and 2050, the report adds. At present, UK North Sea producers are only on track to deliver 4 Bboe of that demand, although an additional 2 Bboe-plus might be feasible if more new projects went ahead.

Disappearing hubs

Some of the report’s findings drew on a wider analysis of the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) performed by Westwood Global Energy Group, which presented its own take on the industry’s difficulties during a recent roadshow around Britain. Westwood’s Northwest Europe Research Director Yvonne Telford said the decline in UK North Sea production had accelerated since the introduction of the EPL.

“Never has the sector seen so little investment, with many projects on pause. And we have aging infrastructure,” Telford said.

Without urgent reforms, she added, the tax receipts from the sector could, from the early 2030s, be cashflow negative permanently due to its huge decommissioning liabilities.

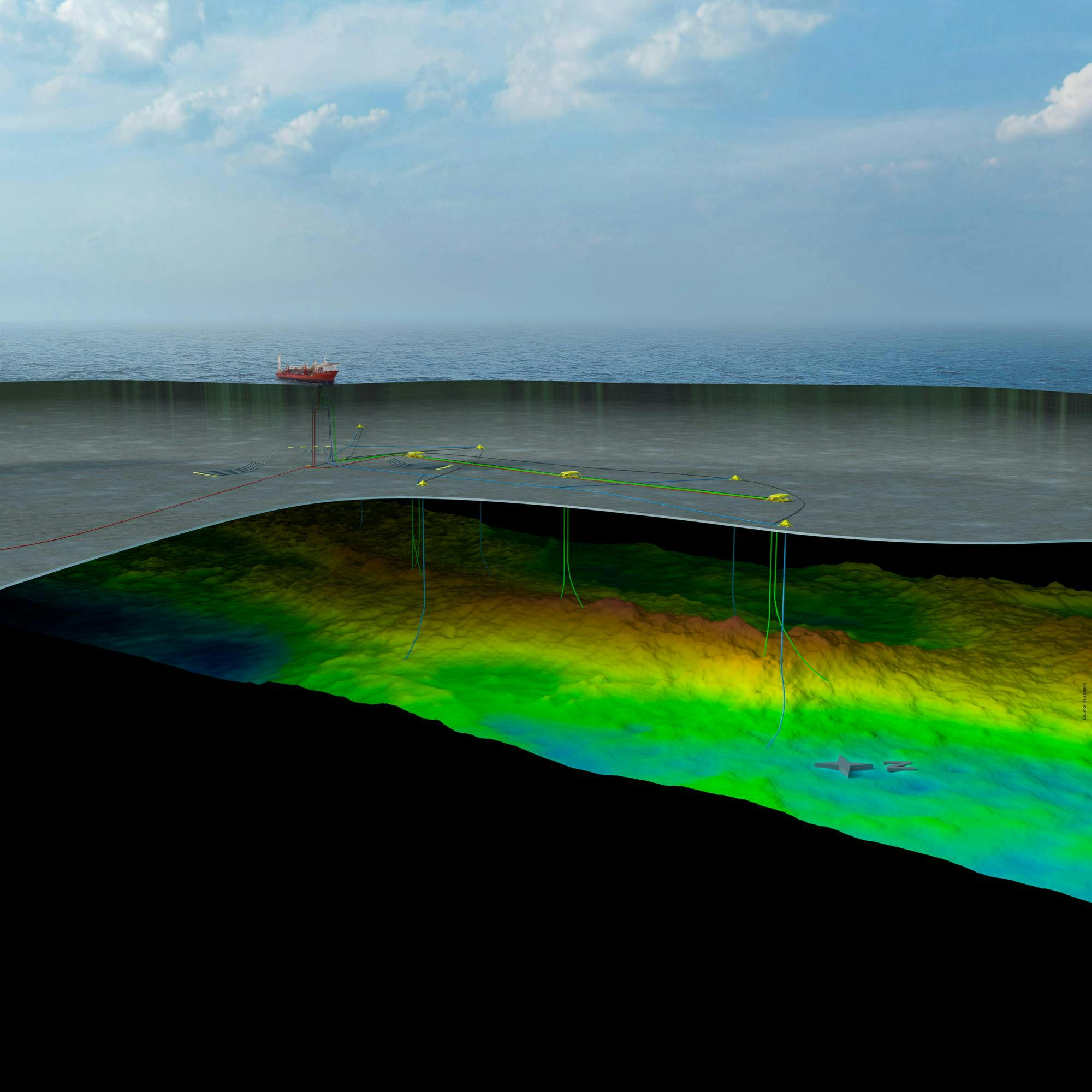

In 2019, when there was still a general consensus about maximizing recovery from the basin, the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) had forecast a gradual decline in production to 1 MMbbl/d in 2040. Now, Britain’s offshore processing hubs are steadily shutting down, from 90 in 2019 to 66 at present. The sector could be left with 43 hubs by 2030 and 20 in 2035, based on current firm investment plans. By 2040, Westwood’s analysis suggests, there could be only four active hubs left.

“The investment picture could still change,” Telford said. “Although time is running out to access the upside potential. If a hub closes, you may lose access for development of the surrounding discoveries and prospects. Then there is the complexity of the offshore infrastructure that takes the produced hydrocarbons to the UK’s various coastal terminals, which in turn support more jobs and the local service sector. If hubs cease, that can impact the reception terminals too. Oil transported through the Forties Pipeline System (operated by INEOS) goes to one terminal, but the gas from the different hub entrants goes to multiple other terminals. The infrastructure has been set up for much higher production throughput rates; it’s very intertwined. And it relies on the different hubs that may export gas export to one route, and oil or liquids to another route... Of the top 10 producing hubs, no two have the same gas and liquids export route.”

There are still widespread development opportunities. Westwood estimates 19 Bboe of technical prospective resources within tieback range of offshore hubs still standing. However, more than 50% is in unlicensed acreage, and until now, the government has consistently ruled out new licensing rounds.

“Licensing is important,” Telford said, “as it allows companies to get those opportunities, work them up, progress them. They could be small, exploration-focused companies right through to the majors…Licensing also demonstrates that the UK is open to business and investment.”

But as the OEUK report pointed out, even where a license has been awarded, it is no longer the case that a new oil and gas project with financial backing will be developed due to the challenges posed by increasingly tight regulations.

Exploratory drilling also faces hurdles. Westwood has identified 16 drill-ready exploration and appraisal (E&A) prospects in UK waters, but the wells keep getting delayed, Telford explained, due to the fiscal and political situation. The list includes two firm commitment wells at Shearwater NE and in the Greater Pegasus Area, four wells that are part of the Phase C license commitment process, and 10 further E&A wells thought to be drill-ready.

With all these negative factors at play, she continued, “you could argue that the UK North Sea has entered an unmanaged decline scenario, but it is also possible to have a more managed decline.”

The picture could change quickly if just one or two of the exploration wells were successful, she added, with the discovered field moving forward to development.

“Under a no-constraints scenario…the UK still has enough opportunities to produce up to 7.5 Bboe, if the investment is there,” Telford said.

Decommissioning burden

As for offshore oil and gas decommissioning, Britain remains a global leader, at least in terms of opportunities. Westwood estimates that more than $26 billion needs to be allocated to shut down UK North Sea operations over the next 10 years, with well abandonment accounting for half the outlay. But the activity at present isn’t organized, with a lack of investment leading to an ever-increasing backlog of wells to be P&A’d, including some that are set to cease production early.

Telford asked, “For the supply chain, how do you plan your business when you don’t know the workload that is to come?”

If the slowdown causes decommissioning costs to escalate, government liabilities to oil companies for this activity will have to rise, she noted. Alternatively, if the government allowed the industry to maximize recovery of the UK’s remaining oil and gas resources, that would increase tax receipts from production while at the same time slowing the coming decommissioning burden.

Telford subsequently confirmed to Offshore that Westwood’s forecast of UK hubs ceasing operations over the next two decades “is based on the economic cessation of production years, determined by our hub model and commodity price assumptions, existing production and expenditure plans. As plans and prices change, the economic outlook can change, and the numbers are therefore providing an indicative trend rather than an exact future outlook.

“There are hubs which have ceased, or are planned to cease, earlier than previously forecast due to changes in investment sentiment," she said. "In these cases, we do see near-field opportunities but without an alternative commercial tieback host. As more hubs cease operating…there is a likelihood that tieback opportunities in the vicinity become stranded.”

Despite the seemingly lack of positives for the sector going forward, significant mergers are still taking place on the UKCS, with Repsol/NEO and Shell/Equinor combining their respective UK operations, and Eni supporting Ithaca Energy. And bp is bringing new fields onstream, such as Seagull and Murlach in the central North Sea.

“The corporate landscape is continuing to evolve in the UK. The European majors continue to be involved, and this should be seen positively for the UK,” Telford said. “Although investment levels have reduced across E&A, development drilling and other capital investment projects in recent years, they have not stopped. That said, there is a distinct slowdown in investment decisions being made on new field developments, which is reflective of the current uncertainty on outcomes of the government’s consultations on the future of North Sea licensing and the fiscal regime for high oil and gas prices.”

Serica Energy, a smaller UK independent, has agreed to acquire operatorship of the Greater Tormore/Laggan area gas field and associated infrastructure west of Shetland.

“Serica is a company that has spoken positively about the business opportunities that exist in the UK upstream sector,” Telford said, “and the deal with TotalEnergies is an example of moving assets into the hands of companies willing to support the necessary investment to maximize economic recovery from that area. Higher gas prices are supporting the business case for investment in gas recovery, but ultimately the lifetime of the hubs—be it gas, oil or both—will be determined by many factors, such as the reservoir, recoverable volumes, costs, investment opportunities, and the fiscal and regulatory framework.”

Scope 3 emissions challenge

Some companies are attempting to move their major new development projects forward. Equinor, Shell and NEO have all complied in recent months with the government’s request to submit new data concerning Scope 3 emissions anticipated from their Rosebank, Jackdaw and Greater Buchan Area developments west of Shetland and in the Central North Sea.

This follows a decision by a court in Scotland last year that the UK government’s original approvals for Jackdaw and Rosebank were unlawful. It was based on the earlier Finch Supreme Court ruling that Scope 3 emissions from oil and gas production must be assessed before new projects can go forward. Shell and Equinor were allowed to continue development work, but the court ruled they would not be able to start production from Jackdaw and Rosebank without receiving new consents. In June this year, the government published new guidance for environmental impact assessments covering the consents that operators now need in the wake of the Finch ruling. The Offshore Petroleum Regulator for Environment and Decommissioning has since sought further information from Shell on Jackdaw’s Scope 3 emissions.

However, a report from Wood Mackenzie in early October found that UKCS production value chain emissions look set to outperform the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's global net zero emissions pathway by 25 to 50 MtCO2e annually through to 2050. Wood Mackenzie estimates that, theoretically, the sector could produce an additional 2.6 Bboe by 2050 that would be within climate science requirements—providing environmental as well as economic benefits.

The government has been considering banning new exploration licenses under its "science-aligned approach" to future UKCS production. But according to Wood Mackenzie's analysis, each additional Tcf of gas produced on the UKCS would save 15 MtCO2e of Scope 1 and 2 emissions when displacing US LNG imports.

“The more the UKCS produces,” said Gail Anderson, WoodMac's research director of North Sea Upstream, “the less emissions will be released, and the less the UK will spend on imports. Such an approach will ensure production for decades to come and support the North Sea’s energy future.”

Based on this analysis, Wood Mackenzie advocated targeted UK offshore licensing in the future, focused on discovered resources that could be tied back to host platforms. Without new licensing, the report noted that by 2035, the UK would rely on US LNG for more than 60% of its gas needs as imports through Norwegian pipelines decline. That would triple the emissions intensity of the UK gas supply from 3.7 to 11.3 gCO2e/MJ by 2035.

Anderson, when asked to explain what the government means by a "science-aligned" approach, told Offshore, “The government’s own data shows that in an ultra-mature basin, you are unlikely to find many more big discoveries. Its view is that exploration will not change the outlook for the UK. Our own data backs that up to some extent. But at the same time, an outright ban on new exploration licenses appears to be unnecessary, especially if your goal is to maintain production for decades to come. Note that the government said it would ban new exploration licenses to explore for `new’ fields in its manifesto before the election in 2024, so it is committed to doing this in some form. But we argue that it’s possible to develop known discoveries as tieback opportunities to existing infrastructure.”

She added, “It is widely known that LNG imports, wherever they originate, will be more emissions intensive than domestic gas supply. The government knows this, but in our analysis, we put some numbers to this by looking as a scenario where an extra Tcf of gas from the North Sea displaces US LNG, which will be where almost all the UK’s LNG imports will come from in the longer term.”

The government’s guidance on Scope 3 emissions from new North Sea projects does not require further mitigation measures and should not be too problematic for the operators, Anderson continued. “Although it will take a bit of time for this to unwind. The EIAs for Jackdaw and Rosebank, resubmitted in July because of the previous legal action, both need timely re-approval by the government to hit their planned start dates. However, even if the government reapproves, a further legal challenge is possible.”

There have been reports that the government was considering selective licensing of acreage with known discoveries. If the government were to follow this course, “that would show that it is listening to the industry while also maintaining its manifesto commitment not to explore for `new’ fields,” Anderson suggested.

The government might also view tiebacks on any acreage awarded—keeping certain hubs going a bit longer—as a way of postponing further burdens on UK taxpayers to subsidize North Sea decommissioning projects.

“This review is one piece of the jigsaw,” she continued. “But the biggest piece is the fiscal consultation, and particularly the possible early removal of the Energy Profits Levy in 2026. If that happens, then I’d expect to see some more investment [in UK offshore E&P]. New entrants are less likely, but certainly expect further consolidation among incumbents on the shelf. I think the government has been listening carefully to industry concerns, and after the October 2024 budget, there has been a more constructive relationship. I think there is cautious optimism about the budget in November, that the investment climate may improve. It all depends on the EPL.”

Even if the outcome of the reviews is positive for the sector, could the new measures still be insufficient to stimulate new UK activity because of the low oil price, finance constraints, and more positive investment climates for offshore oil and gas E&P elsewhere?

“This is very true; it will undoubtedly help if the review outcome is positive, but the global macro picture isn’t so rosy for the UK," Anderson concluded. "That said, you’ve got to try to do what you can. Many companies are reviewing capital budgets for lower prices in 2026, so even if the EPL was removed early, we can’t expect a massive immediate reaction, it might be 2027 before things fully pick up.”

About the Author

Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

Jeremy Beckman has been Editor Europe, Offshore since 1992. Prior to joining Offshore he was a freelance journalist for eight years, working for a variety of electronics, computing and scientific journals in the UK. He regularly writes news columns on trends and events both in the NW Europe offshore region and globally. He also writes features on developments and technology in exploration and production.