Technical advances reduce time from discovery to production, says EIA

Bruce Beaubouef • Houston

Technological advances in oil and natural gas development and the increasing availability of existing infrastructure are reducing the interval from the discovery of commercially recoverable hydrocarbons to production, while at the same time allowing new discoveries that are smaller in size to be economically viable. This is especially true in the deepwater U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GoM), according to the US Energy Information Administration's (EIA) "This Week in Petroleum" of Oct. 5.

In June 2011, Eni began producing oil at its Appaloosa field in the deepwater GoM, just a little over three years after it was discovered in the Mississippi Canyon area in water depths of about 2,500 ft (762 m). But for delays associated with the temporary deepwater drilling moratorium in the wake of the Macondo accident, production might have commenced even earlier.

Noble Energy's Santiago field, with a depth of about 6,500 ft (1,980 m), was the first deepwater GoM discovery issued a permit following the temporary drilling moratorium; and it is expected to be brought on stream in less than a year from that time. This very short discovery-to-production interval, particularly for an "ultra-deepwater" field (water depth of at least 5,000 ft), is possible in part because Santiago is part of a three-field joint development called Galapagos, which includes the Isabela and Santa Cruz fields now under development that were discovered in 2007 and 2009, respectively.

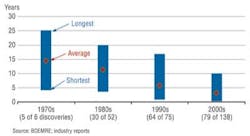

The timetables for Appaloosa and Santiago reflect a marked acceleration from typical experience during the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, when the average interval from discovery to production for deepwater fields was 11.4 years, 5.9 years, and 3.3 years, respectively. The comparatively quick turnaround for many of the more recent GoM discoveries primarily reflects their proximity to existing production and transportation facilities put in place during development activity associated with earlier discoveries. Several 2000's-vintage discoveries at locations inaccessible to existing infrastructure have taken much longer to reach production – between seven and 10 years.

Technological advancements in subsea development systems are also playing an important role. Fields that may have been considered too small, deep, or remote to develop using production platforms in the early phases of deepwater exploration are being tied back via subsea flow lines to existing platforms, significantly reducing both costs and the lag from discovery to initial production. Appaloosa, for example, is producing through a 20-mi flow line connected to the Corral fixed steel production platform situated in the shallow-water GoM shelf. The Galapagos fields will be tied back to BP's Na Kika semisubmersible platform, which currently serves as a production hub for several other deepwater fields.

Better technologies for subsea completions and improved access to drilling and production equipment designed for deep and ultra-deep waters have also facilitated exploitation of deeper and more remote discoveries. While roughly equal to platform developments through the 1990s, subsea developments have accounted for over three-quarters of deepwater GoM field production starts since 2000. Only about a third of the GoM's deepwater platforms were installed prior to 2000, and less than 10% before 1990. In 1996, Shell acquired Alaminos Canyon area leases in the far southwestern portion of the GoM, but the lack of drilling rigs capable of operating in ultra-deep areas delayed exploratory drilling until 2002. That year, Shell announced the Great White discovery, a several hundred million barrel field located in about 8,000 ft of water. In 2004, the company followed up with the nearby Silvertip and Tobago discoveries, each in water depths of over 9,000 ft. A solution for commercially developing these deep and isolated fields would not be in place until 2006. About three more years were required for fabrication, delivery, and installation of production and transportation facilities for Shell's Perdido development, comprising all three fields. Great White, the first to reach production, was finally brought onstream in early 2010.

Deepwater Gulf of Mexico: Duration between field discovery and production, by decade of discovery.

Deepwater Gulf of Mexico: Production starts by decade.

Looking forward, the EIA report observed that location will continue to play a key role in determining development options and timelines for both existing and new discoveries. For several of the larger existing finds, especially those in very remote ultra-deepwater portions of the GoM, production is still several years away. For example, Chevron's joint development of the ultra-deepwater Jack and St. Malo fields is not expected onstream until 2014. The fields, each in water depths of about 7,000 ft, were discovered in 2004 and 2003, respectively, but Chevron and its partners did not reach a final development decision until late 2010. The fields' locations – in the Walker Ridge area of the GoM, far from existing infrastructure – necessitates construction of new production and pipeline facilities. Once installed, though, these facilities can serve as a development hub for any future discoveries in the vicinity, thereby significantly reducing the interval from discovery to production.

Anadarko, BP settle Macondo damage claims

Anadarko Petroleum Corp. reports it has agreed with BP to settle "all current and future claims against Anadarko associated with the Deepwater Horizon event."

The agreement calls for a $4-billion payment to BP by Anadarko. BP will release its $6.1 billion in claims against Anadarko and forego reimbursement for any future costs related to the accident.

In addition, BP will indemnify Anadarko for damage claims under the Oil Pollution Act, claims for natural resource damages and associated damage-assessment costs, and any claims arising under the relevant Joint Operating Agreement. Anadarko also will transfer its 25% interest in Mississippi Canyon block 252 (Macondo) to BP.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com