FLOATING PRODUCTION: Early post-mortem of P-36 sinking indicates variety of difficulties

William Furlow

Senior Editor

Veronica Murillo

Business Editor

As committees meet and the Brazilian government conducts various investi-gations into the sinking of the P-36 semisubmersible drilling and produc-tion vessel, the bulk of production from Brazil's giant Roncador field lies shut-in below almost a mile of water column

While the P-36 vessel was fully insured ($500 million), operator Petrobras has a $50 million/ month question to answer. How do you replace the largest floating production vessel in the world when the market for such rigs remains tight?

There are several options, including some involving the P-40 Marlim Sul rig sitting in the harbor near Rio de Janeiro, but the company must move fast enough to protect its projected growth figures for the year.

Sinking post mortem

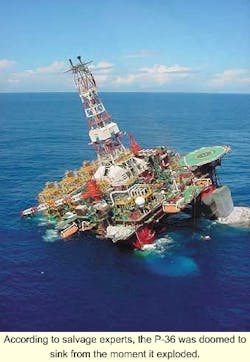

Following the gas explosions, the P-36 was bound to sink, no matter what. That's the opinion of several Smit International officials, who were among the salvage crew flown in from the Netherlands to rescue the crippled and sinking rig. Once the explosions damaged one of the vessel's support columns, there were too many problems to overcome to halt the slow settling of the unit.

Reports state that the fire and explosions occurred too quickly for the vents in the damaged column to be closed before evacuation. While 165 crew members safely made their way off the vessel, a firefighting team remained aboard to battle the blaze. With a firefighting team on board, the vents were kept open to remove smoke and assist firefighters. As the vessel took on water and began to tilt, vents that were originally designed to remain high above the water's surface submerged, allowing more than 3,000 tons of water to pour into the hull and lower deck areas.

Smit International mobilized soon after the explosions occurred, and divers and salvage engineers were on site within two days. Lars Walder, corporate communications manager for the salvage company, said his divers accessed the damaged column 160 ft below the water line.

Purging the hull

Underwater, the divers worked to install new valves and access existing valves so that nitrogen could be pumped into the column. Nitrogen was used to displace the incoming water while minimizing the risk of further explosions. "We were able to stabilize it over the weekend (March 17-18) and Monday," Walder said.

Smit succeeded in clearing the water from several chambers inside the column and welded closed some of the leaks below the water line. Walder said the rig is so large that it would have been difficult to identify all the potential sources of leaks. "There must have been more damage than we were able to see," he said.

Although divers continued to go down alongside the rig's hull, the unit was becoming unstable and dangerous. Once the angle of tilt reached 30 degrees, the vents that circulate air through the column allowed water to come in. "This was difficult to stop," Walder said.

The team realized soon afterward that it was a lost cause. Walder said his people left the rig about three-to-four hours before the unit actually sank. At that time, the weather was growing worse, and so was the flow of water coming into the column. The water was entering from so many places, the team determined there was no way to stop it.

Cause of explosion

Petrobras has not said exactly what caused the explosions on the P-36, but was initiating various investigations to determine the sequence of events. A number of reports indicate that there was a gas or a gas leak in the suspect column, and that the gas ignited. At least one report indicated the ignition source apparently came from some activity within the column or nearby, and that workers involved could have been killed.

A preliminary report on the incident should be ready by early May, but the bigger question now is what will be done with Brazil's largest offshore field. Prior to the accident, all 21 subsea wells were shut in, although only six were capable of producing at the time. While the rig appears to be a total loss due to the water depths, the fact that Petrobras operates without subsea manifolds means that the subsea wellheads probably were not damaged in the accident and subsequent sinking. The exception to this good fortune would be the settling of the rig on one or more of the subsea wellheads.

If this accident had occurred on a field where production wells were drilled through a template below and routed to a nearby manifold, it is possible the sinking of the rig would have damaged the subsea manifolds, templates, and wellheads.

Petrobras' solutions

Fortunately, the outlying position of the seafloor wells means Petrobras could possibly bring in a number of smaller production rigs to handle parts of the estimated 180,000 b/d production Roncador was eventually expected to produce. Petrobras reportedly has considered using the P-40 semisubmersible, designated for Marlim Sul, to take on some of the Roncador production.

This rig has a capacity of about 150,000 b/d and could handle the 84,000 b/d the P-36 was producing when the accident occurred. The P-40 is awaiting an environmental permit before going into service this summer on Marlim Sul.

If Petrobras decides to pursue this avenue, there is the long-term question of finding a rig to replace the P-40 on Marlim Sul. In the meantime, there is still production coming out of the Roncador field, thanks to a small production vessel nearby that is handling about 13,000 b/d. This vessel has a capacity of 17,000 b/d, but not nearly enough to solve the field's problems.

Options Petrobras is reportedly considering include the following:

- Leasing a new unit: A new production unit could be leased to take the place of the P-36. This would have to be a very large vessel, since the P-36 was considered to be the largest floating production unit in the world. With a tight production floater market out there for both semisubmersibles and monohulls, finding a replacement may prove difficult.

- Converting the P-47: The P-47 floating storage unit was receiving production from the P-36 before the event and was not damaged during the sinking. That unit could be converted to a floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) vessel to handle production from the field.

- Other vessels: There are other small production vessels owned by Petrobras that could pitch in to make up the projected 180,000 b/d.

Whatever the company decides, the loss of the P-36 itself was covered by insurance, and the real question is how to get production back on line quickly enough to make a difference this year. Reports state that having the field offline is costing the company $50 million per month.