Joint industry project seeks to advance subsea standardization

Bjørn Søgård

Tore Irgens Kuhnle

Bente Leinum

DNV GL Oil & Gas

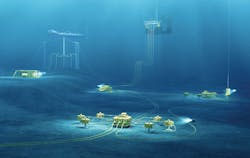

Subsea production systems are an integral part of FPSO and other floater-based field developments, as well as for new tie-ins to old installations.

Over the past 15 years, subsea technology has moved from subsea wells, manifolds, flowlines, and templates, to include subsea boosting, separation, and now compression.

In the near future, deepwater wells will require more complex subsea equipment. Looking further ahead, the industry expects to see automated production entirely located on the seabed, piping oil and gas directly to shore through the “subsea factory” concept.

The recent downturn in the oil and gas market has led to a greater focus on cost efficiency. Though cost has always been an integral part of offshore field development, falling oil prices have forced the subsea industry to reassess what counts as best practice in the manufacturing and employment of subsea equipment.

To this end, the industry has begun a series of joint industry projects (JIPs), led by DNV GL, to set guidelines and recommended practices in five areas: re-engineering, workovers, component catalogues, compliance with established standards, and standardized documentation. A sixth JIP, dealing with specifications for forgings, has already resulted in a new recommended practice.

JIP goals

The overall aim is to cut cost, lead-time, and uncertainty, and thereby help the subsea industry stay competitive. The need is obvious when a single project may have as many as 80,000 associated documents.

The standardization discussion began three years ago, when it centered on making identical parts. It quickly became clear that a unified tool box of products and equipment did not go far enough to harmonize processes and procedures, and could even cause more inefficiencies and fragmentation. The core challenge lies in the fact that oil companies have different technical specification requirements, and suppliers have tailored their subsea equipment according to what the end customer specified. As a result, similar equipment, doing similar jobs, may for example be made out of different steel depending on the end customer.

This bespoke style of manufacturing makes for elevated costs and extended lead times. Standardizing is about creating predictability throughout the supply chain, not necessarily identical components. The automotive sector is a clear example of standardization in practice. Though manufacturers make different versions of a standard car, the factory line, materials, processes, and procedures are essentially the same.

The Subsea Documentation JIP aims to come up with a recommended practice which provides a minimum set of documentation requirements for all major subsea components. Increased predictability will improve industry practices, and this will help operators, contractors, and suppliers better understand and manage their subsea documentation. In turn, they will all benefit from reduced lead-time; reduced documentation requirements and replications; enhanced experience transfer; transparency; and improved quality. However, what is really important is that various players in the industry are loyal to the agreed guidelines.

A lack of trust

The oil and gas industry is still struggling to grasp the principle of standardization, and at the same time there is a lack of governance and a degree of distrust in the industry that impedes the process of standardization.

Joint innovation and smart standardization are critical to strip back complexity and in turn, lower costs and enable rapid and efficient technology implementation. The industry needs to get the balance right on when to trust and when to interact. Trust needs to be built through improved governance with all parties pulling together in the right direction.

When an operator orders a new piece of equipment, the level of interaction required between the operator, the regulator, the certifier/verifier, and the manufacturer adds to the scope and adds layers of complexity to the process without adding value. The industry needs to arrive at a new equilibrium where the scope is reduced, allowing the industry to operate at a reasonable margin to be sustainable and have a healthy business.

Costs have increased mainly due to inefficiencies and scope creep. Unproductive activities come, as mentioned, from unnecessarily complex specifications. At the same time, there is too much scrutiny in design, engineering and testing, and not enough trust that each party is doing their job properly.

As a result, operators have become overly concerned with the basic components that make up the equipment, rather than concentrating on more fruitful areas, such as optimizing on a system level. This issue has now been partly tackled with the publication of the Recommended Practice (RP) for Steel Forgings for Subsea Applications, resulting from a two-year JIP.

Looking to the future

Subsea processing is now a real alternative to conventional technologies, but there are currently limits to its widespread adoption and hence on its potentially transformative effect on the industry.

For brownfield projects, the various technologies may be used alone or in combination with other technologies. In contrast, an all-subsea solution has more limited applicability for greenfield projects. The most likely near future all-subsea greenfield applications are oil and gas field developments in mature geographies. Gas discoveries that only a few years ago were assumed to be developed with subsea compression to onshore LNG liquefaction are now instead moving in the direction of floating liquefaction, FLNG. For deepwater applications, all-subsea solutions need to overcome shortfalls related to power, complexity, and availability.

A DNV GL JIP is being initiated to work toward standardization of subsea processing. The first step will be to define a functional description and a specific plan for standardization for subsea pumping. Phase 2 will continue with subsea separation and injection and subsea compression. The outcome of the JIP will be a guideline and a DNV GL Recommended Practice for industry use.

What’s next

Major JIPs, such as DNV GL’s work on subsea standardization, stand to shake up relationships at every level of the offshore value chain. The growing complexity of subsea systems is starting to have an ever-increasing impact on an operator’s ability to effectively monitor, inspect, and repair affected systems. Moreover, the challenges of designing and employing original equipment in even deeper water will only further restrict an operator’s ability to respond to fatigue and failure efficiently.

Having a clear focus on collaboration and innovation gives the industry a neutral ground for businesses, and will enable regulators and advisory professionals to come together to develop solutions to complex subsea challenges quickly and effectively. Standardization will be important to secure a strong and coordinated mutual approach in order to achieve the goal of more profitable subsea developments.

The key to achieving this is to create predictability throughout the entire supply chain to allow optimization at every step. Smarter standardization will still allow for customization through configuration of standard modules, while also streamlining work processes involved in designing, manufacturing, and operating technology. This will enhance quality and drive a profitable and reliable subsea future.

The authors

Tore Irgens Kuhnle, M.Sc., is Business Development Leader for SURF in DNV GL Oil & Gas in Norway. He has ten years of experience within different areas of the oil and gas industry, lately as principal researcher within subsea processing. Kuhnle started as consultant within business risk management, working with field development investment decisions and due diligence. Later, he moved to finance as head of risk for more than ten hedge funds during the financial crisis. He then became investment manager for hedge funds, working with both investments in listed companies as well as private equity. Kuhnle has been director of the board of an oil company and a number of technology companies.

Bjørn Søgård, M.Sc., is Segment Director Subsea and Floaters with DNV GL Oil & Gas. He has been in the subsea industry since 1991, and has played a key role in the research, design, and engineering management for several large subsea EPC projects. Søgård is currently Segment Director for Subsea and Floaters with a global responsibility to coordinate across geo-divisions and technology units within DNV GL. Throughout his career, he has worked to develop and improve international standards for the subsea industry.

Bente Helen Leinum, M.Sc., is Senior Principal Consultant-Business Framework and Management Advisory for DNV GL, with a main focus on the operation of subsea systems. She has extensive experience in oil and gas industry research and development, with a specialty in the field of failure analyses-materials technology and project management. Her responsibilities include project management and participation, RBI-analysis, pipeline integrity management projects, verification projects, fabrication control, field inspection, laboratory work and experiments.