Evolved into fast-track project

Frank Hartley, Drilling/Production Editor

The Lorien subsea development in the Gulf of Mexico began as what could be considered a conventional subsea tieback, but it evolved into a fast-track project where problem solving, risk mitigation, and adaptation to change became critical. There were significant challenges to overcome with flow assurance, host platform modifications, installation resources, and the 2005 hurricane season, according to Kevin Nance, project manager for the Noble Energy-operated Lorien project.

Lorien is Noble Energy’s third significant deepwater project to start production over the past seven months, and follows the start-up of Swordfish in October 2005 and Ticonderoga in February 2006.

The discovery

The Lorien field is located in Green Canyon block 199 in 2,177 ft of water and is a two-well subsea development with a 12-mi tieback to a host. Field production began on April 27, 2006, and achieved its gross production target of approximately 19,000 b/d of oil and 25 MMcfd of natural gas. Noble Energy is operator, with a 60% working interest. Hydro Gulf of Mexico, L.L.C. has a 30% working interest, and Davis Offshore, L.P. has a 10% working interest.

ConocoPhillips discovered the field with the TransoceanPathfinder drillship in July 2003. In April 2004, Noble purchased ConocoPhillips’ interest. Noble Energy initiated discussions in May 2004 with Shell to start production via subsea tieback to Shell’s Bullwinkle platform.

The Lorien project team in December 2004 thought that first production in December 2005 was achievable, with production of 30,000 b/d of oil and 48 MMcf/d of gas. The project was expected to be a conventional development that would lend itself to a fast-track schedule.

Drilling & completion

Drilling was challenging due to high formation pressures and small margin over the frac gradient. This led to extremely tight control, with nine casing strings including two expandables. The wells were drilled underneath salt, through known shallow saltwater flows.

Details had to be worked around surface faulting, shallow gas, potential mud flows, and hard pan areas to pick an acceptable site. Two preset anchors avoided flowlines already in place. Additional anchoring was a challenge because of the number of flowlines already in place.

Noble drilled the first well with two sidetracks in the No.1 well in December 2004, Nance said, and found an oil line in March 2005. Then, by May 2005, Noble completed the flow assurance plan. The No. 2 well was drilled in June 2005. The surface locations are 300 ft apart. The final production string was 7 in., which allowed for the original capacity of 15,500 b/d of oil. Each well had a Cameron subsea tree.

Diamond Offshore’sQuest was used for the completions. The completion section of the wells encompassed 20 ft of shale separating a 100-ft water sand. Too much laminated oil sands were fractured separately. Core analysis determined correct acid and additives.

Fluid analysis and flow assurance was hampered, so offset well information and expert opinions were used for flow assurance and project development. The first fluid analysis was 38° API oil, 1,350 GOR, 100° F, and BHP - 13,000 psi. Since wax deposition looked like it would be a problem, Cameron was asked to include two more chemical injection lines for the trees.

Host platform

The host platform, Shell’sBullwinkle facility, can handle over 200,000 boe/d. There were significant differences in philosophy, standards, codes, and procedures but Nance said Noble learned a lot from Shell regarding spacing, how to move and operate safely, procedures, and accepted practices. At the time, Shell was starting a drilling program and would continue through completion of Noble’s surface tie-in. The project involved working in simultaneous drilling and surface operations, which meant there was no hot work area on the platform. If something broke or did not fit, it could not be modified unless in a welding habitat. A virus infected many of the crew, which shut down operations for 10 days. Shortly after that, four hurricanes passed through the Gulf, and the New Orleans offices for Shell and the contractors either relocated or temporarily shut down.

Tieback

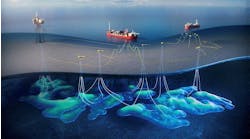

The seafloor presented problems for pipelines due to marine life clusters. Nance said Noble laid the two flowlines about 150 ft from these clusters with an ROV recording the positioning.

Another challenge for the flowline route came at the host platform, with its five subsea tiebacks and multiple oil and gas pipelines. Shell agreed to let Noble abandon and remove two existing 3-in. flowlines. Prior to removal of the lines, Noble used a sealing pipeline plug to protect them from internal corrosion while offline.

The umbilical and flowline installation were delayed 84 days and 26 days, respectively, because of a scheduling conflict.

Nance said Caldive’s shore base did an excellent job of welding the 2,000 ft flowline, having a repair rate of less then 1%, and reeled it onto theirIntrepid vessel without incident. The pipe was coated with enough polyurethane to maintain adequate heat to prevent wax and hydrate formation for even lower than expected flow rates. Noble saved more than $1 million versus a pipe-in-pipe installation, he said.