Hydraulic fracturing advances could resolve tight gas dilemma offshore Norway

The Norwegian Offshore Directorate (NOD) is inviting the industry to address ways of developing Victoria, one of Norway’s largest untouched offshore gas discoveries.

Exxon discovered the field in the Norwegian Sea in 2000 with exploration well 6506/6-1. Six years later, Total assumed operatorship and drilled an appraisal well in 2009.

However, technology at that time meant that profitable production would be unlikely. That led to relinquishment of the surrounding production license 211 in 2018.

Per Valvatne, senior reservoir engineer at the NOD, speaking at a seminar in Oslo, said companies should revisit Victoria.

“Yes, it’s a tight reservoir at significant depths, with both high temperature and high pressure, as well as a high content of CO2," Valvatne said. "Nevertheless, a study indicates that current well technology, combined with hydraulic fracturing, could allow production of substantial gas volumes.”

The acreage around the field will be available under Norway’s next APA (Awards in Predefined Areas) licensing round.

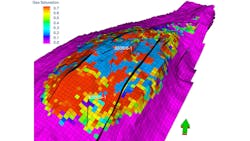

According to Arne Jacobsen, assistant director of technology, analyses and coexistence at the NOD, said analysis suggests about 140 Bcm of gas in-place at Victoria, with four development wells potentially delivering 29 Bcm over a 30-year lifespan.

UK consultancy Opecs has assisted the NOD in its evaluations, including a geo-mechanical study of the discovery. Opecs’ report found that modern hydraulic fracturing techniques could improve well productivity sufficiently to sustain profitable production.

Victoria, in 400 m of water and about 4,800 m subsurface, is 10 km from infrastructure serving the Dvalin field, and 50 km from Heidrun and Åsgard.

The study found that four wells could theoretically produce 10 MMcm/d of gas and sustain that volume for almost two years. It may be possible to add further wells to raise the recovery threshold.

To date, hydraulic fracturing offshore Norway has been applied mainly in chalk reservoirs, whereas Victoria is in a sandstone reservoir.

Jacobsen said there have been technology advances.

“Fluids and propping agents used in hydraulic fracturing have improved, the vessels used are better, and we’re also able to deal with higher reservoir pressure and temperature," he said. “These operations can also be done faster and with greater reliability, thus reducing costs and uncertainty.”

There are other Norwegian discoveries in tight reservoirs. If technology can unlock Victoria as a commercial gas source, these other fields too may become viable.