South China Sea offers opportunities, challenges

Wendy Laursen

Contributing Editor

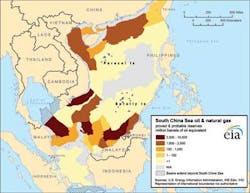

Offshore E&P activity in the South China Sea is growing, driven by the potential of its deepwater reserves and the rising Asian energy demand. But the South China Sea also poses development challenges, most notably in the form of boundary disputes among China, Vietnam, and the Philippines.

Asian economic growth is driving demand for increased oil and gas production in the South China Sea. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) predicts local demand for liquid fuels to grow 2.6% annually and that local demand for gas will grow 3.9% annually over the next decade. China, in particular, aims to significantly increase its consumption of natural gas by 2020 and the South China Sea, with its potential for new gas discoveries, is a focus area.

Most offshore oil and gas development in the South China Sea is close to shore, but China has progressively moved into deeper waters, notably in the Pearl River Mouth basin. The potential for further development of the region's deepwater reserves, however, is heightened by the aforementioned border disputes.

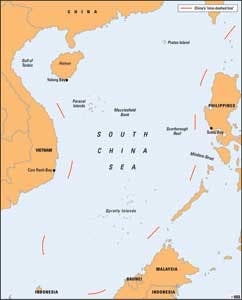

The main areas under contention are the Spratley Islands (with a total land area of less than 3 sq mi/7.8 sq km) and other small island groups including the Paracel Islands, Pratas Island, and Scarborough Reef. China bases its claim to the islands on historical expeditions and an official map with a nine-dashed line published in 1947. Vietnam also claims the Spratly and Paracel islands, and in 1956 the Philippines claimed Scarborough Reef and part of the Spratly Islands.

Current production

Most offshore developments are within the respective country's exclusive economic zone.

CNOOC is the most active of China's national oil companies in the South China Sea and is working with Husky on the Liwan gas field that has an estimated 4-6 tcf in proved and probable reserves.

As local fields such as Duri and Minas decline, Indonesia's PT Pertamina is hoping to boost production with new acquisitions in the South China Sea. These include Natuna's D-Alpha block and blocks in Vietnam's Nam Con Son basin.

The Palawan basin is a major source of domestic gas for the Philippines. The Malampaya platform there is operated by Shell in a joint venture with Chevron and the Philippine National Oil Co.

Thailand's largest oil field is Chevron's Benjamas field in the north Pattani basin. Also in the basin is the country's largest gas production at Bongkot with BG Group.

PetroVietnam has partnered with a number of foreign companies to develop offshore fields. Chevron currently operates major contracts in the Cuu Long and Phu Khanh basins. Other big investors include, Eni, ConocoPhillips, and French independent Perenco.

Singapore aims to become involved in the South China Sea and has acquired exploration rights to blocks in the Gulf of Thailand, the Pearl River Mouth basin, and offshore Indonesia.

Brunei's largest oil and gas field is Champion, and the Southwest Ampa field accounts for most of the country's gas production.

China's energy needs

Currently, 15% of China's oil and gas comes from offshore. However, the country is adamant about the South China Sea, says Paul Aston partner at Holman Fenwick Willan Singapore, because its onshore reserves are starting to dwindle. A third of its current reserves are offshore and of these, 33% are in the South China Sea, most in deepwater.

Aston recently returned to Singapore after four years in Shanghai. He says China's dependence on foreign oil rose to 56.3% last year, and its dependence on natural gas imports rose to 21.5%. China will continue to be a major importer, with or without the South China Sea, says Aston. By 2030, its demand for liquid fuels will grow by 70%, and it is expected to be importing 75% of this.

"China is not just interested in the South China Sea. It wants to be a major player offshore," says Aston. "It is now competing with the likes of Keppel, Jurong, and Daewoo to be a major builder of rigs, not just for Chinese companies but all companies. There are people who say there are quality problems but 20 years ago people said the Koreans couldn't build LNG vessels, now they build 85% of them. China is building jackups. They are building heavy-lift vessels, pipelaying vessels, and they are building dive support vessels - everything they need to operate as an EPC contractor in competition with companies like McDermott, SapuraClough, and Technip."

China does not yet have the same level of deepwater expertise as some Western oil majors, says Gabe Collins of US analysis initiative China Signpost. He expects China to bring in overseas partners to develop the deepwater assets of the region, and oil majors with big interests in China are unlikely to partner with other countries like Vietnam to develop contentious fields if it means souring relations with China. However, he says, working in conflict zones is the nature of the oil and gas industry. "Think of a place like Iraq," he says. "Or think of a place like Nigeria, or South Sudan. Companies will go into very hostile environments if they think the molecules are there."

Reserve estimates

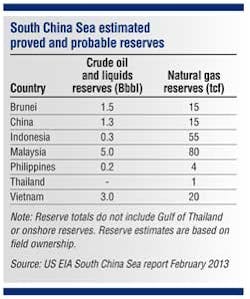

The EIA estimate for the area stretching from Singapore and the Strait of Malacca to the Strait of Taiwan is approximately 11 Bbbl of oil and 190 tcf of gas in proved and probable reserves. Most conventional hydrocarbons reside in undisputed territory.

However, EIA admits that it is difficult to make an accurate estimate because of under-exploration and the territorial disputes. The contested Spratley Islands have virtually no proved or probable oil reserves and industry sources suggest less than 100 bcf of gas. However, a US Geological Survey (USGS) 2010 analysis resulted in an estimate of 0.8 to 5.4 Bbbl of oil and between 7.6 and 55.1 tcf of gas in undiscovered resources.

The contested Paracel Islands do not have significant discovered conventional oil and gas fields, and geological evidence suggests the area does not have significant potential. However, the area may contain significant natural gas hydrate resources.

Børre Gunnerud, partner at Wikborg, Rein & Co., says that, as with the reserve estimates further north in the South China Sea, the estimate of 10 tcf of gas in the 27,000-sq km (10,425-sq mi) disputed area between Thailand and Cambodia should be treated with caution. Gunnerud advised the Cambodian National Petroleum Authority (CNPA) for several years on the overlapping claim area in the Gulf of Thailand.

"There is very little data," she says. "The numbers are very sketchy."

The geology is also very fragmented and recovery success may be as low as 10%.

The USGS notes the complexity of the tectonic history of Southeast Asia. This history has included rifting and attenuation of continental crust, opening and closing of ocean basins, development of regional fault systems, and local uplifts. The petroleum systems are mainly Cenozoic basins and the gas is focused into younger, post-rift elastic and carbonate reservoirs.

EIA predicts gas reserves will be more viable than oil in the South China Sea. However, producers would have to construct subsea pipelines in areas with submarine valleys and strong currents in deepwater, says EIA. The region is also prone to typhoons, precluding cheaper rigid drilling and production platforms. Tension leg tethering of production installations and managed pressure drilling to operate in high-pressure deepwater environments may be a way forward.

Energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie estimates only 2.5 Bboe for the South China Sea, and in November 2012, CNOOC estimated 125 Bbbl of oil and 500 tcf of gas in undiscovered resources.

EIA points to the sensitivity of the area for global trade. Approximately 14 MMb/d of crude oil pass through the South China Sea and Gulf of Thailand, almost a third of global oil movement, according to data from Lloyd's List Intelligence and GTIS Global Trade Atlas. Around 6 tcf of LNG, over half the global LNG trade, passed through the South China Sea in 2011, according to data from PFC Energy and Cedigaz.

Business as usual

Despite the tensions and uncertainty, there are huge areas of rapid project development in the South China Sea, says Nick Haslam, managing director of London Offshore Consultants' Singapore office.

"There are also smaller pockets of inactivity - for example, the Gulf of Thailand where little is going on at present, but overwhelmingly the region is a hive of project activity. All told, upstream projects in the South China Sea region can be valued in excess of $26 billion."

The Malay Peninsula, East Malaysia, Vietnam, and Indonesia probably constitute the areas of highest project concentration. It is difficult to ascertain reserves in the region but it is reasonable to assume they are abundant, says Haslam. The number of projects active and upcoming in areas such as East Malaysia, the Malay Peninsula, and offshore Vietnam are evidence of this.

"Brunei is a territory to watch closely," says Haslam. "Historically, Shell has held an effective monopoly on Bruneian oilfields. But things are definitely changing. The country seems keen to engage other energy majors. We have been engaged by Total, for example, to provide warranty services for a development to the northwest of Brunei."

CNOOC expects 10 new offshore oil and gas fields to come onstream this year, among which the Liwan 3-1 gas field will become the first big deepwater gas field offshore China. First gas at Liwan is expected late 2013 or early 2014. Liwan has an estimated 4-6 tcf in proved and probable reserves. The Liwan project is in block 29/26,300 km (186 mi) southeast of Hong Kong in the South China Sea, and spans 979,773 acres (3,965 sq km). Husky Energy operates the development and holds a 49% interest; CNOOC holds the remaining 51%. CNOOC maintains a stake of at least 51% in any offshore development in China.

Additionally, CNOOC will drill around 140 exploration wells, acquire approximately 15,400 km (9,571 mi) of 2D and 24,800 sq km (9,575 sq mi) of 3D seismic data, and will continue to expand deepwater exploration activities. This will involve an investment of over $20 billion. In June 2012, CNOOC offered nine oil and gas blocks to foreign bidders in part of the South China Sea overlapping Vietnam's 200-mile exclusive economic zone in the Jiannan and Wan'an basins. According to EIA, no foreign companies have publically made a bid.

Chevron acquired new acreage in the South China Sea in 2012 through the acquisition of shallow water blocks 15/10 and 15/28 in a production-sharing agreement with CNOOC. The company also has an interest in deepwater block 42/05, which covers an exploratory area of approximately 1.3 million acres (5,216 sq km), not in contested waters.

Eni has been present in China since 1980 and has 10 licenses there. The company signed a production-sharing contract with CNOOC in 2012 for the exploration of block 30/27 situated approximately 400 km (248 mi) off the coast of Hong Kong. The block covers an area of around 5,130 sq km (1,981 sq mi) in one of the most promising parts of the Chinese offshore sector.

A changing environment

"We are always assessing new opportunities in the region," says Ron Morris, ROC Oil's president in China. "In some cases the boundary disputes have had some impact on pursuing and securing new opportunities, but ROC has a rolling 20-year plan so we continually review all blocks. China is an ever-changing environment. Every year is different, every month if not every day."

ROC is a 19.6% interest holder in the Beibu Gulf Project that achieved first production in March. The project partnership also includes Horizon Oil, 26.95%; CNOOC, 51.0%; and Oil Australia (Majuko Corp), 2.45%. The first phase of the project sees oil production from the Weizhou 6-12 North and 12-8 West fields in block 22/12, about 60 km (37 mi) from the southern coast of China, adjacent and connected to CNOOC's W12-1 field complex. The project involves the construction of a jointly owned, purpose-built processing platform and two production platforms in 30 m (98 ft) of water and their total integration with existing CNOOC infrastructure.

Along with the production commencement news came confirmation that the results of the three exploration/appraisal wells drilled on the WZ6-12 North and South structures during 2012 have led to an increase in certainty of the reserves in some of the reservoirs, as well as additions from the discovery of new pools in WZ6-12N and the Sliver prospect. The result is a 25% overall increase in proved and probable reserves. Upon completion, a total of 10 wells drilled from the WZ6-12 platform will be connected to the production system, compared with five in the original development plan. Production will progressively ramp up through the year as development wells are completed and brought online. Ultimately, the new processing platform will also enable CNOOC to bring other marginal fields in the area online.

For Morris, the project has been a success on several levels. Firstly, there were the technical challenges. The geological characteristics of both fields and the properties of the crudes are quite different and difficult. Additionally, W12-8W had to be accessed by drilling horizontally above a layer of water and below a gas cap.

It would have been uneconomic under conventional thinking, says Morris. The project was, therefore, a landmark in that all parties had to cooperate to minimize project costs and to share the existing infrastructure.

"Together with CNOOC, we had to put a common hat on and ask how the project would be developed if we were one company," says Morris. "With different management philosophies, it took some time."

It was a way of cooperating not seen in China before, says Morris, and it enabled capital and operational costs to be reduced by half.

For example, synergies were achieved by allowing produced water to be injected into CNOOC's existing water disposal wells.

Typically, joint ventures in China have been on a stand-alone basis, with an independent entity producing alone and exporting through its own export system. Therefore, the standard contract had to be rewritten for this project so that CNOOC was appropriately compensated for its existing assets, and the operational synergies were realigned to the satisfaction of all partners.

Several traditional barriers were eliminated so that win-win outcomes could be achieved.

The oil spills at the ConocoPhillips' Penglai 19-3 oil facility in Bohai Bay, northern China, caused a significant delay while all parties re-evaluated risks.

"It had an impact on everyone," says Morris.

His company, ROC, experienced several months of delays during project signoff as a result of the spill.

"I believe we are yet to see the full impact of that. China is definitely changing the way they are looking at accountability of businesses and putting in new regulations to make sure that the proper controls are in place," says Morris.

China is an important market for ROC, and Morris is positive about the ground work done to date with CNOOC. While he believes the possibility of big oil discoveries in shallow water offshore China are less likely, a medium-sized specialist player like ROC thrives on the opportunity to extract value from mature or difficult to develop fields. The company promotes this proven capability as a valued service not only for national oil companies in China, but throughout Southeast Asia.

New challenges

There will be technical challenges ahead for the industry, says Ernst Meyer, DNV's regional manager for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Gas is becoming a bigger focus than oil and with it new competencies will need to be developed. Many recent finds, for example, have been characterised by sour gas or high CO2 levels. The move toward deeper waters will also bring technical challenges, but perhaps more importantly, new safety challenges.

"The regulatory regime in the area is not very well developed," says Meyer. "It works well if things are easy and simple, but I think it will be a major challenge to maintain acceptable safety levels without really independent regulators in the South China Sea. In some countries the national oil companies are acting as regulators whilst having an interest in the resources and their development."

Still, Meyer believes the region is attractive to oil companies, particularly when compared to regions such as the Arctic, where project costs are expected to be high.

"If you can get access to good projects and good development sharing agreements in Southern Asia, and if you can solve all the political and technical issues, I would say it is a much more profitable area to be in at the moment," he says.