Disconnectable FPSO technology opens new markets in Gulf of Mexico

Mitch Provost, Provost Management

The Gulf of Mexico deepwater oil and gas industry continues to search for more efficient ways to produce fields without being exposed to catastrophic or high economic risks. Fresh experience with the forces imposed by naturally occurring environmental events have generated great interest in finding a solution to protect these large investments. While disconnectable FPSO technology is new to most, it is well-known to many that have been using it for years. The concept: simply to avoid perilous conditions.

Development constraints

For years it has been acknowledged that risers are the vulnerable link for a deepwater floating production system. Historically, risers have been hard pipes attached to a jacket leg of a fixed platform in shallow water. Large steel jacket legs ensure the riser is protected and safe during extreme events. Floating structures are not rigidly attached to the seafloor and tend to have high motions during extreme events. Anything attached to it, such as risers, also must respond to motions.

The job of the flowline riser is to transport usually high pressure produced fluids from the wellhead to the process facilities on the topside. More applications with limited subsea processing of fluids are becoming available. However, it may be some time, and with high development expense, before all processing can be accomplished subsea. Until then, there will continue to be a need for topsides processing systems and a means to safely transport produced fluids from the seafloor to that system.

Risers typically are thick-walled steel pipes with diameters sufficient to allow desired flow rates of produced fluids without too much restriction. Great attention is paid to the properties of the fluid and how they will change when traveling through the pipe. If the changes are not predicted carefully, the flow can be interrupted and cause expensive shutdowns for remediation.

The primary types of risers used in deepwater are rigid pipe and flexible pipe. Rigid pipe risers are made of high-strength steel sufficient to withstand the internal fluid pressure, external hydrostatic pressure of deepwater, and temperature differentials between the hot flowing produced fluids and colder seawater. Flexible risers are a composition of helical metallic wires and extruded thermoplastics that provide sufficient strength while allowing more flexibility than a rigid pipe. Because they are more flexible than rigid pipe, they normally require assistance in supporting their own weight in deepwater and have limited application in ultra deepwater.

Rigid risers on floating platforms are often referred to as SCRs or steel catenary risers. SCRs are installed in a catenary, or natural drooping curve, configuration to allow maximum movement of the floating structure without imposing excessive stress on the pipe. It is a delicate balance of forces and material properties to design a rigid riser for a floating structure considering not just the movement that the floating structure will impose, but also any strong water current present. Additionally, the forces near the “touch-down point” (spot where the pipe meets the seafloor) can cause considerable fatigue damage.

Flexible risers can be installed in a variety of configurations. In addition to the traditional catenary configuration, other variations include assisted buoyancy to support the riser in mid-water (“lazy wave” configuration) to allow maximum flexibility while reducing stress on the heavy riser.

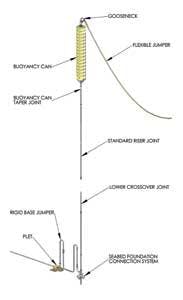

Another variation is a hybrid riser consisting of a rigid portion and a flexible portion. These risers consist of a pipe tower similar to a drillstem riser with a short flexible riser connected at the top, just below the water surface. This combination can withstand the high hydrostatic pressures and vertical weight of deepwater without touch-down concern while allowing flexibility for connection to the floating structure.

While great strides have been made in riser design to decouple moving floating structures from the fixed seafloor, the response of a structure in extreme environments and over long periods of time is the driving force in its design and the limitation in protecting the entire system. Floating platforms consequently have been designed to minimize motion, especially heave or vertical displacement, to minimize loads on the risers. This is difficult considering that anything floating must contend with the balance of buoyancy forces and wave forces.

Traditional structures

Platform designs, such as TLPs, spars, and deep-draft semisubmersibles, strive to minimize heave. The TLP accomplishes this with rigid tendons (pipes) securing the structure to the seafloor. If a tendon fails, the structure becomes unstable and can capsize as seen in the GoM during Hurricane Rita. Spars and deep-draft semis attempt to accomplish this with deep drafts that provide stability and a dampening effect on vertical motion.

While attempting to maintain a fixed dimension between the structure and the seafloor, the nemesis of this concept is the wave. Since all of these structures accomplish their primary objective fairly well (keep vertical displacement to a minimum), they are vulnerable to waves that reach the topsides deck and impose extreme forces on the structure. To prevent this, these structures are designed with a large separation between the deck and the water surface.

Unfortunately, higher deck elevations increase the vertical center of gravity. A high center of gravity creates higher instability and requires more draft or stronger securing arrangements, thus increasing overall costs. It was discovered during hurricanes Opal (1995), Ivan (2004), and Katrina (2005) that maximum wave heights (particularly wave crest heights) are much higher than previously predicted. As a result, API has developed new design criteria with higher wave heights. This means even higher deck elevations and higher associated costs.

New concept for GoM

If the weakness of protecting the risers in extreme environments can be eliminated and if deck elevation becomes inconsequential, structures could be designed much more efficiently. One method of achieving this is the disconnectable ship-shaped FPSO. Since these units are ships, once disconnected they can sail the seas as all other ships do, thus avoiding extreme environments. Additionally, the riser design can take advantage of lower ultimate loading since extreme motions will be greatly reduced.

Today’s technology for disconnection includes valves and flanges suited to safely separate the riser pipe. The riser hangs directly from a buoy (instead of an appurtenance on the hull). The buoy is attached to and detached from the hull, making a mechanical connection. The riser pipe mates with a special flange that can create a strong seal to prevent produced fluid escape. There are several proprietary designs for this connection. Valves are placed on either side of this flange that quickly close before disconnecting.

Most of the disconnectable buoy configurations include a weathervane feature. This allows the ship to turn into the approaching wind and waves to minimize the forces on the hull and to minimize hull motion and station keeping requirements. The buoy rotates within the receiving structure on the ship to allow this. The riser pipe on the ship is routed through a stack of swivel joints that allow produced fluids to flow at high pressures while rotating 360°. As with disconnectable flanges, several proprietary designs are available for swivels. Most use toroidal shapes with axial seals.

One function of the buoy is to keep the risers suspended in the water when disconnected to eliminate large changes in riser configuration. Another function is to provide a common connection point for the risers. The buoy is stationary at a water depth a few hundred feet below the surface. This keeps the buoy (and risers) out of wave action during hurricanes and below the higher rate currents coming from loop or eddy circulation.

Armed with a disconnectable system consisting of a buoy and weathervaning swivels, the FPSO no longer is restricted to location and can plot courses to remain a safe distance from hurricanes. This not only protects the large investment of the ship and production system, it helps to ensure continued production once the storm passes.

Developing market

As a new addition to the fleet of options for deepwater structures, the disconnectable FPSO expands the possibilities of field development. The interest in developing these units is growing with the acceptance of this technology. Many FPSO providers have been waiting for the opportunity to exploit the GoM, but have been met with a shy market. The introduction of a new product into an established market means that the first customer will be the testing ground and few companies are willing to take this risk.

Baby steps are required to break into the market and the initial one has been made. The first disconnectable FPSO unit is scheduled to start producing in the GoM in 2010. This will establish a proving ground and discovery of more opportunities to be exploited. The question now is how quickly others will follow. Several GoM deepwater developments are considering FPSO as the long-term solution, while others are considering it for early production. Either way, the future is preparing for a new market of offerings and many are welcoming it with great anticipation.

About the author

Mitch Provost is a professional engineer, project management professional, and founder of Provost Management, a deepwater consulting firm. He has assisted Helix Energy Solutions Group as a project manager on the Helix Producer I, the first ship-shaped disconnectable FPU (floating production unit) for the GoM. He is also a member of the API RP 2FPS revision task group and has authored the new section on disconnectable floating production systems.