Strengthening Asia-Pacific demand increases Australian E&P investments

Julian Callanan, Dr. Roger Knight - Infield Systems Ltd.

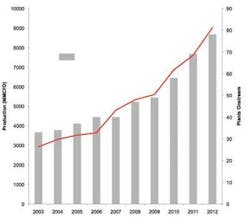

Looking at the profile of investment in Australia over the next five years, Infield Systems forecasts total offshore infrastructure capex to rise steeply to a peak in 2010, then settle with annual average offshore capex solidifying in the region of $4 billion per annum. This is much higher than in the preceding five years, and reflects the work necessary to achieve the increasing production levels shown in the first of the accompanying graphs.

Key in driving increasing investment in Australia’s offshore sector is the growing global demand for energy resources. This increase is strong around the Asia-Pacific region, where a 2007 IEA report predicts China and India alone will account for 45% of the global 50% increase in energy demand to 2030. The pressure to find energy resources for these growing countries has become more acute with the transition of Indonesia from a net exporter, to a net importer of hydrocarbon products. Australia, with an established culture of developing natural resources, and a geographical position conducive to servicing these markets, is jostling to fill this shortfall.

Complementing Australia’s ability to do this is its undeveloped gas reserve base, and the predisposition of Asian countries to consume gas. In China, recent legislation to clear up the growing environmental pollution problem there prioritizes cleaner burning fuels such as gas rather than coal. In India, such is the rate of population and industrial growth that a desperate race to secure energy is under way. Finally, in Southeast Asia, despite a natural abundance of gas, the overzealous exploitation of this to fuel rapid economic growth has meant that countries such as Thailand and Malaysia, which both source approximately 70% of their energy from gas, now confront the problem of a lack of new discoveries in relation to consumption. As a result, recent years have seen an explosion in both the number of LNG regasification plants planned and constructed in Asia, and the diversity of countries they are to be constructed in. While recent global economic turbulence may lead to a slight reduction in the overall demand, the underlying structural changes within these markets mean that even a low case scenario is likely to lead to significant increases in demand.

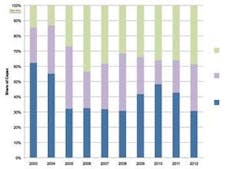

Since demand for gas is increasing, and this will be a profitable revenue stream for Australia’s offshore sector, it has already started to shape the orientation of offshore capex. Interestingly, this has happened in a manner contrary to that which we would expect to see from a youthful, developing basin. Mature hydrocarbon production zones, such as the Gulf of Mexico, have shown increasing tendencies to spend more on subsea structures, as opposed to the platform, pipeline, and control line market segments. This is a consequence of many years of investment in platforms and export lines, resulting in the opportunity to link new wells to existing infrastructure at little extra cost.

The North West Shelf of Australia, which has nothing like the sustained investment found in the Gulf of Mexico, already has delivered a significant level of subsea spending in relation to other offshore market segments. This disparity is caused by the size of the gas fields offshore Australia, and the lack of a major domestic market to buy the gas.

Taking the greater Gorgon area as an example, this 40 tcf field cluster is Australia’s largest single gas project. It is between 130 km (81 mi) and 200 km (124 mi) offshore Western Australia and is to be developed using about 35 subsea wells and manifolds, installed between 2011 and 2019, in water depths between 200 m (656 ft) and 1,300 m (4,265 ft). While much of the gas reserves of the NWECS went directly onshore to the energy hungry markets of Europe, in Australia, a country with only 20 million people, this market is covered by the established North Rankin and Goodwyn fields. As a result, Chevron, the lead operator of the Gorgon project, has promised domestic sales only if prices in the Western Australian market rise to be comparable with that of the target Asia market, which is to be served through the development of a large LNG facility at nearby Barrow Island.

Barrow Island is unique. Historically designated an environmentally protected area, it fell within the exclusion zone of the British atomic weapons testing program conducted at the Montebello Islands through the 1950s. This eroded its protected status, and now, with 455 producing wells delivering 300 MMbbl of oil since 1967, it is Australia’s largest onshore oilfield development. Barrow Islands’ importance to the hydrocarbon industry is set to increase as the first phase of the Gorgon LNG liquefaction facility gets under way. The recently revised scheme is now set to have three, rather than two, 5 million metric tons (5.5 million tons) per annum trains in place by 2017, with the first phase operational from 2013, the second from 2015, and the third from 2017, according to plan.

While Australia’s subsea industry expects consistent growth over the short- to mid-term, the fledgling deepwater industry is growing more rapidly. Here, key fields such as Jansz, Pluto, and Scarborough, will account for in the region of $5 to $6 billion of investment over future years. The 100% Woodside-owned and operated Pluto, based in deepwater, 190 km (118 mi) offshore Karratha, Western Australia, has an interesting development concept, and is on track to record one of the fastest discovery-to-production times for a gas field. One key problem bringing this field onstream is its distance from shore. Using subsea wells, then piping the untreated gas over 200 km (124 mi) would have placed the export lines in jeopardy of corrosion, or overt hydrate formation. To overcome this, glycol would need to be mixed with the gas; this is intended to be done on shallower water production platforms in 80-120 m (262-394 ft) of water, before the mixture is taken to shore via a 36-in. (91-cm) carbon steel export line. Once ashore, the glycol will be separated from the gas then pumped back to the production platform, while the gas is liquefied and subsequently exported, predominantly to the established Japanese market.

However, acting as a potential handbrake to the growth of the deepwater market, and potentially threatening the completion of projects such as Pluto, is the relatively inelastic supply of skilled offshore labor, and deepwater capable equipment required to undertake the number of projects. In this regard Australia faces its own set of circumstances. Firstly, being geographically adjacent to Southeast Asia, good, skilled, cost-effective labor for large scale construction and fabrication is on the doorstep. However, given the relative age of the offshore industry in Australia, a lack of experienced (20 years +) personnel, may constraint activity, and contribute to some projects coming in over schedule. This set of circumstances is different from those in more mature hydrocarbon production basins, where average employee experience is higher, and local labor is typically much more expensive, with large scale fabrication and construction usually sourced from much further afield, incurring additional post-build transportation costs.

A further problem area we are seeing developing is that of operational safety. Australian legislation and associated operating standards are comparable to other more developed areas such as the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico; as such, experience, and skills relating to safety are particularly valuable in order to meet the high standards set here.

Equally important in putting a potential limitation on project go-ahead is the availability of mobile offshore drilling units (MODUs). Infield currently records some 19 MODUs operating in Australian waters; eight capable to operate in up to 500 m (1,640 ft) of water, with only one capable of going to 1,500 m (4,921 ft) water depth. Total current contract value is in the region of $2.7 billion, with average contract length being 15 months, and average contract value being $145 million. We anticipate new MODUs to enter the Australian market in the near future, driven by the lack of deepwater capable vessels, and also by the large demand caused by subsea developments such as Gorgon and Pluto, which will need to be installed, inspected, and maintained with semisubmersible rigs.

Outside of these constraints there is little reason why the offshore industry of Australia, which historically ebbs and flows as projects, government, industry, and environmental protestors have aligned or misaligned, should not continue to advance and grow over the coming years. Understanding and quantifying energy demand from the Asia-Pacific region may be an emerging art, yet recent economic structural change and sustained population growth alone puts pressure on many of the countries in Australia’s sphere of influence to look to secure energy sources well into the future. Subsequently, a large proportion of Australia’s prospective onstream gas resources already are committed in long-term contracts with countries all the way around the Pacific Rim.

Infield Systems’ associate analyst, Julian Callanan, and data manager, Dr. Roger Knight, look at the growing offshore industry of Australia, discuss what drives key developments in the area, and what may limit this market’s future growth.

Developed from the “Infield Systems Ltd. Asia Pacific Report 2008/12” which covers the offshore industry in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole, this article profiles the amount and orientation of offshore capital investment forecast for Australia over the next five years. Mentioned are the key projects and potential problems which may hinder their progress, and the progress of the wider push to increase production in the country. Although Australia produces both oil and gas, development of the large gas reserves found right across the North West Shelf, offshore Western Australia, is driving much of the increased capital expenditure here.