Growth in gas projects to dominate upstream development

There is little doubt that the global natural gas industry is poised to dominate the world’s upstream development stage during the next decade. Major gas discoveries made during the last several decades that were once considered “stranded” are now at the forefront of development strategies as operators look to monetize gas in an increasingly attractive global market. As the momentum builds on the development of major gas projects, the industry will face the familiar challenges of replacing produced reserves and developing infrastructure to move an increasingly valuable product to market.

In 2003, natural gas production exceeded the 100 tcf threshold for the first time, increasing 3.4% over global gas production in 2002, and will continue to rise as new projects are brought to their full forecast potential.

The greatest regional increase (23%) came from Sub-Saharan Africa, where Nigerian production was boosted by full-year production from Nigeria LNG train 3, which had come online in November 2002. Similarly, in Latin America, the 6% increase in production was largely attributable to the first full year of production from Trinidad’s Atlantic LNG train 2 and the startup of train 3 in April 2003. Also, increased production from Qatar and Saudi Arabia contributed significantly to a 13.8% increase in natural gas production from the Middle East.

Looking out over the longer term, production from the Former Soviet Union will expand to serve European and Far East markets, while Europe will be relatively stable. In the CIS, the major limitation imposed by export pipelines is now in the process of being overcome, and production will rise as new pipelines are constructed and the Sakhalin, and possibly Arctic, LNG schemes are developed. In Europe, the UK, the world’s fourth-largest gas producer, may have entered gas-production decline in 2003, but this will likely be offset in the near future by increased production from Norway’s Ormen Lange super-giant gas field and the Snøhvit LNG development.

North America saw a minor gas production decline of less than 0.2%, since a slight increase in US production was insufficient to offset the decline in production from Canada. Meanwhile, developments in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico have been steadily building momentum. Since 2000, almost two-dozen deepwater projects have come onstream, with about half starting production in 2002. Frontier areas such as Alaska and the Mackenzie Delta hold promise for future gas developments in a region where demand will far exceed indigenoussupply during the com- ing decade.

Based on IHS Energy’s analysis of likely future developments around the world, excluding the onshore and US Gulf of Mexico shelf, there are more than 250 primarily gas-focused greenfield developments or major expansion projects expected to contribute production within the next 10 years.

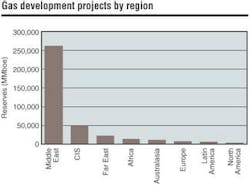

We expect nearly 100 super-giant or giant (> 500 MMboe) projects to contribute to global production during the next decade. The continuing development of the North Field/South Pars complex and the future development of several other major gas projects in Iran drive the gas development scene in the Middle East. While the field sizes of the Middle East dominate the reserve picture, the CIS has the largest number of potential gas developments in our analysis, including the Phase III of Karachaganak in Kazakhstan, Shtokmanovskoye in the deepwater offshore Russia, and the continued development of the Sakhalin Island projects.

Major offshore developments in Indonesia, including Natuna in the longer term and Tangguh in the more near term, should attract significant investment from current operators during the next several years. Development of several giant projects onshore China (Kela 2 and Tazhong 1) and the development of major deepwater gas developments in Australia (Sunrise and Gorgon) will contribute significantly to global production in the next three to five years.

This geographic profile clearly shows that the importance of gas around the world is no longer confined to the regional suppliers that have traditionally fed the major markets in North America, Europe, and Japan.

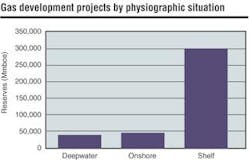

The vast majority of reserves associated with near-term development projects is found in the shallow-shelf waters around the globe, primarily due to the massive resource of the North Field/South Pars complex.

Based on our analysis, there are 123 onshore gas development projects with average gas reserves of 324 MMboe per project, while 126 projects located in shallow waters have a similar average-reserve base of 344 MMboe of gas reserves, when the North Field/South Pars is excluded. In contrast, the deepwater has far fewer projects (only 37), but the average gas reserves-per-project is more than 850 MMboe (500 MMboe if we exclude the huge Shtokmanovskoye deepwater project in Russia).

Looking forward, the volume of projects and the total reserves found onshore and in shallow waters around the world will ensure continued development, but super-sized developments in the deepwater will attract significant, long-term attention.

Development timing

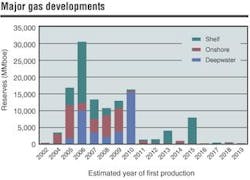

Our analysis indicates that the industry is on the verge of a significant growth in the development of upstream gas projects. Our method of forecasting the timing of gas projects worldwide is based upon a combination of historical data, available industry announcements, engineering design estimates of production levels, and timing using known gas reserve sizes.

We expect first production from many major gas projects, accounting for more than 60 Bboe in reserves, to occur within the next three years and then be sustained at relatively high levels throughout the forecast period. Although we forecast the year of first production, we have not attempted to forecast annual production volumes, but clearly, the development of many of the super-giant and giant projects will take many years and significant, sustained investment to reach their full potential.

Although excluded from our analysis, drilling in the GoM should continue well into the next decade, based on an analysis of existing field-size distributions for known discoveries across North America. The remaining and yet-to-find (YTF) resources for the offshore GoM shelf stand at approximately 35 tcf, and are concentrated into a fairly narrow size range that is highly sensitive to exploration, development, and operating costs. With another 30 tcf in deepwater gas resources remaining or YTF, the GoM region comprises about one-third of the estimated total undiscovered gas potential in North America.

Given the amount of natural gas development that has occurred around the world during the last decade and the significant amount of development that is expected during the next several years, pressure to sustain exploration activity to replace produced reserves will begin to build late in the forecast as the known resource-base is produced.

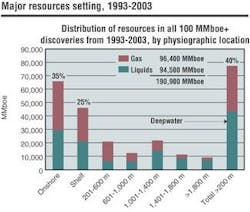

In 2003, global energy exploration rebounded only slightly after two years of declines in discoveries of 100 MMboe or more. Perhaps the most notable feature of the major 2003 discoveries was the dominance of deepwater success, with a record 70% of all major discoveries being made in water depths below 200 m and 65% in water depths greater than 1,000 m.

IHS Energy’s estimate of resource additions from new natural gas discoveries in 2003 is 67.9 tcf, about 2% more than the 66.6 tcf estimate for 2002 (re-estimated from 57.3 tcf a year ago). These estimated natural gas resource additions in 2003, however, replaced only 66.7% of 2003 production - continuing a three-year trend in which discovered gas resources have failed to replace production.

The global gas market is poised to grow and to dominate the focus of the global energy industry in the years to come. Major development projects from super-giant fields in the Middle East, CIS, and indeed, around the world, will lead the globalization of natural gas. Along with this growth, specific challenges will arise that are not new to the industry and certainly not without attention from the major stakeholders.

Reserve additions to replace production will be increasingly important and more difficult to find. If the trends continue, the deepwater will be the source of many major-reserve additions, while the shelf and onshore, with historically shorter cycle times from discovery to development, will be critical sources for the industry to keep pace with rapidly growing demand in the near-term.

Development of infrastructure required to move gas from supply centers to growing demand markets will also continue to be a primary challenge faced by operators and governments seeking to monetize gas assets and meet demand growth. Inter-regional pipeline infrastructure will continue to be critical to the development of the global gas market. Some examples include proposed infrastructure that would connect Eastern Siberia with China and infrastructure that would link the frontier areas of Alaska and the Mackenzie Delta with the rest of North America.

Of course, the role of LNG will continue to push the boundaries of regional markets as the known resource base is significantly more dispersed relative to demand than at any time in history. In a world where energy is the lifeblood of the global economy, the economics of supply and demand will most likely ensure that natural gas will find its way to markets around the world.