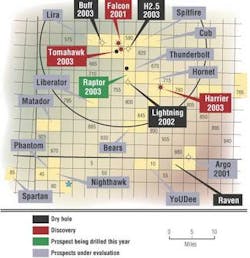

Pioneer flying high in Falcon corridor

With four discoveries – one onstream and three under development – the 32-block Falcon corridor investment in the Gulf of Mexico has paid off for field operator Pioneer Natural Resources Co.

Falcon went onstream in March, and Pioneer hopes to bring Harrier on in December and Raptor and Tomahawk on in mid 2004, said Deep Trend President Matthew Doan, who is consulting for Pioneer in the series of projects. Doan spoke recently at a Marine Technology Society luncheon in Houston. The success in the Falcon corridor brings an unexpected problem to the newcomer in deepwater operations: The four-slot manifold was not quite enough to handle the anticipated flow.

null

"We didn't think we'd have this much success this early," Doan said.

Falcon, a 32-mi subsea tieback to Falcon Nest, produces about 195 MMcf/d. The operator expects to begin compression on the field within the next six months, he said. Pioneer projects a four- to five-year lifespan for the Falcon field, located on East Breaks block 579 in 3,400 ft of water. The El Paso-operated Falcon Nest platform is in 390-ft water depth at Mustang Island block 103.

Pioneer sanctioned the Harrier development earlier this year as a single-well, 47-mi subsea tie back to Falcon Nest. Harrier, on East Breaks block 759 in 3,600 ft of water, holds estimated gas reserves of 55-80 bcf. Pioneer expects gas from Harrier, combined with production from Falcon, to reach 275 MMcf/d.

"It's a very aggressive project," Doan said.

The Harrier completion occurred in late August, Doan said. Umbilicals have been delivered and are set for installation in September. The pipeline should be installed by November to go onstream in December.

Due onstream next year, the Raptor and Tomahawk fields will feature short tie-backs to Falcon Nest, which has a capacity of 400 MMcf/d.

The Harrier and Tomahawk fields have a projected lifespan of up to three years, he said.

"These wells are not going to last very long, so we have to be very aggressive in our exploration program out there," Doan said.

Pioneer, which initially held 45% interest in the Falcon field, purchased additional interests to gain the operatorship of the field before completely buying out former partner Mariner Energy's interests. Falcon, Pioneer's first operated deepwater project, went onstream two years after the first well was spudded. Then-operator Mariner sanctioned the project in October 2001.

Doan said Pioneer attributes the speed with which Falcon was brought onstream to using a building-block approach.

"Using building blocks, standard solutions, we didn't go through elaborate tree studies" to determine what type of tree to use, he said. Pioneer and Mariner opted for the Cameron horizontal trees that Mariner had on hand for the project. "We used what we knew would work."

The standard solutions approach extends to control systems and other areas, as well, Doan said.

"Having a lot of this equipment ordered as early as possible helped us get it online as quickly as possible," he said, adding that Pioneer is also using this approach with the fields now under development.

Gas shortfall continues despite LNG permit activity

Even as state-of-the-art LNG receiving terminals are installed, they'll incorporate new technology at a rapid pace, said Jim O'Sullivan, Technip Offshore's senior vice president for marketing, during the sixth annual Global Forum for Engineering and Construction at Rice University.

The fist LNG receiving terminals in the Gulf of Mexico could come onstream as early as 2005, but O'Sullivan expects 2007 as the more likely arrival time of the first receiving terminal in the Gulf.

Despite the number of terminals under consideration, not one final permit had been issued as of early September. Ten terminal permit requests have been filed for onshore US, in addition to the five offshore GoM permit requests. Of those, three are for onshore California and two offshore California. One is for onshore East Coast. Of the remaining nine, three are for offshore GoM and six are for onshore along the Gulf Coast. O'Sullivan doesn't expect any of the California terminals to be onstream before 2010.

One permit has been filed for the Bahamas, and five have been filed off Mexico, with four of those on the Baja California side.

In the long run, O'Sullivan said, locating the terminals over the border will help but will not be a final solution because of infrastructure. The "not in my backyard" (Nimby) risk is a timing risk, just as technology is a timing risk that can likely be mitigated.

The industry has tended toward manmade islands to serve as the receiving terminals. They provide flexibility because they don't require specialized carriers but do allow mid-ship loading, he said. There is no single point mooring, so the setup will allow alongside berthing. The downside, he said, is that there would be less than 80% accessibility in the Gulf. El Paso's Energy Bridge proposal is a bit different, he said, but it will require specialized vessels.

One technological advance that will "make a huge jump in annual availability" in the Gulf is a floating cryogenic hose, which is under development, O'Sullivan said. These hoses should be available in 2006-2007. The terminals now being designed will not likely include them as an initial feature but rather as an immediate upgrade on installation, he said.

"Supply is the main driver" for the number of receiving terminals under consideration, he said. The concern for supply is tied directly to supply coming from the Gulf of Mexico, he said.

"The shelf peaked in 1997 and has been in decline ever since," O'Sullivan said. "There's no coming back."

Gas is now being found in the deepwater GoM, but lack of infrastructure for transportation could hamper development of those reserves, he said.

Combine a declining shelf with an increasing demand, and LNG receiving terminals make a lot of sense. The problem, he said, is even with a concentration on LNG import, there will still be a shortfall of 1 tcf/year through 2010.