F. Jay Schempf

Contributing Editor

It comes as no big surprise that there are slightly more mobile offshore drilling units currently in the Gulf of Mexico than there were a year or so ago, just before the fatal Macondo explosion and oil spill caused an almost complete shutdown of GoM drilling.

Currently, the total Gulf rig fleet numbers 125 units of all types, according to figures supplied by ODS-Petrodata. This compares with 123 such units a year ago. This minor increase exists despite seven deepwater and five shallow-water rigs having left the area during the federal government-ordered drilling moratorium of May-October 2010.

Pride International’s new deepwater drillshipDeep Ocean Mendocino will be ready to drill Petrobras America’s second well at the Cascade field when the drilling permit is handed down by BOEMRE.

Much of the fleet increase, however, consists of newly built rigs, some of them of the deepwater variety, which sailed from overseas shipyards into the Gulf to begin drilling for the first time under pre-Macondo contracts. Existing units transferred to the Gulf make up the rest. These also came in to fulfill contracts in both deep and shallow water signed prior to the disaster.

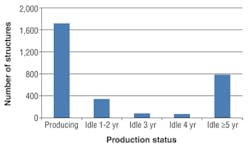

The trouble is, only a few of the deepwater rigs in the Gulf are actually working. Most are on standby, awaiting federal government approval of drilling permits for the various offshore operating companies. Shallow-water units fare a bit better.

Despite low pre-Macondo rig utilization rates in the Gulf (63.4% in the first week of May 2010), utilization is even lower at the same time this year (56%). Chalk most of that up to the six-month official federal drilling moratorium, and an additional four months during which, while an increasing number of shallow-water permits were granted, still no deepwater contracts had been approved by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement (BOEMRE), the U.S. Interior Dept.’s regulator of drilling and production in federal waters.

Late this past February, however, Gulf operators breathed a somewhat bated sigh of relief when BOEMRE began awarding permits for deepwater wells. But by mid-May, only 12 such permits had been approved, and it was evident that obtaining drilling permits from BOEMRE – particularly for really new deepwater wells – continues to be constrained by an arduous regulatory review process.

The fact is that the majority of the 12 BOEMRE-approved deepwater permits were resumptions of projects already approved by the Minerals Management Service – predecessor to BOEMRE – prior to Macondo. So far, only a couple have covered actual new deepwater exploration.

According to Michael R. Bromwich, BOEMRE director, the permits were granted because the operators involved complied fully with the bureau’s rigorous safety and environmental requirements, and each had demonstrated the ability to contain a subsea oil spill by contracting with either the Marine Well Containment Co. (MWCC) or Helix Well Containment Group. Both are consortia of deepwater operators who have gathered technical expertise and resources to develop deepwater well containment response systems capable of being deployed immediately to any location in the Gulf.

Speaking at the recent Offshore Technology Conference in Houston, Bromwich said the deepwater permitting process has moved forward with “appropriate” speed while still meeting the bureau’s new, more rigorous standards.

Whatever the velocity, the pace of deepwater permitting approvals is considerably below average. According to the most recent edition of the Gulf Permit Index, published by Greater New Orleans, Inc., since February, the average number of deepwater Gulf permits issued to date was 1.3 permits per month, compared to the historical average of 5.8 per month – a 78% reduction.

Switching to all drilling in the Gulf, Bromwich added that to date, BOEMRE had approved 51 shallow-water (less than 500 ft water depth) permits since last summer, the pace of which he said is “somewhat below” the historical average (According to U.S. Congressional sources, the pre-Macondo issuance of shallow-water permits averaged 7.1 per month, but the current average is 3.5 per month).

The hard line bites back

The BOEMRE, backed by Bromwich, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar and President Barack Obama, has taken a strict stand on deepwater permitting, insisting from the day BOEMRE was created that only deepwater permits that meet the bureau’s stricter safety and environmental standards, and demonstrate the necessary containment capabilities will be approved; and that those that do not will be rejected (i.e. sent back for revisions).

While the majority of offshore operators have heeded BOEMRE’s call for higher levels of safety and readiness for drilling in deep and ultra-deep waters, the slow pace at which such approvals are being handed down has become a sticking point that’s reverberating across the country. The effects are being felt throughout the Gulf Coast regional economies, and concern is growing about the recent sharp increases in the price of crude oil on international markets.

For sure, recent unrest in the Middle East and in North Africa has influenced prices in world crude markets. In the USA, however, a significant dichotomy exists within BOEMRE itself, one that has raised frustration levels all across the offshore industry and in the Gulf Coast region in particular. The problem is that while the bureau has created the lofty new rules and regulations with which to more thoroughly govern the industry’s actions, it has lacked the resources with which to do it. What’s more, offshore operators claim the agency continues to issue addendums to new regulations on an almost weekly basis, forcing them to modify drilling permit request documents they have just submitted. This can only mean even longer delays.

Additionally, Bromwich and Salazar recently noted they are considering rules that would affect subcontractors such as drilling companies and other drilling service providers, a broad step beyond the agency’s original role as regulatory overseer of offshore operators and one that probably would require congressional approval. The potential result: more pesky delays.

These and other sources of uncertainty have created an attitude of mistrust between the industry and BOEMRE, which in some cases has resulted in federal lawsuits filed to force the agency to grant drilling permits that complainants say have met all requirements.

Finding the folks

The truth is that BOEMRE does lack the resources it says it needs to do its job – in terms of both personnel hiring and funding of new, high-tech equipment necessary for its permit application reviews. In a March interview, Bromwich said one of the principal problems faced by the MMS (and later, BOEMRE) has been a fiscal “starvation diet” which has existed for decades. After Macondo, the bureau was criticized for having only 60 inspectors to monitor some 4,000 offshore facilities in the Gulf.

To solve the problem, President Obama called for an additional $100 million to go with his earlier fiscal 2011 Interior Dept. budget request of $364.8 billion. The extra expropriation, said Interior officials, would enable BOEMRE to hire an extra 41 people to the roughly 50 in the permit division and help add 116 more inspectors to supplement the 50 or so already employed.

But only a part of that request was honored in April via a continuing resolution in Congress to provide the Interior Dept. with $68 million more to its fiscal budget, for both BOEMRE and the Office of Natural Resources Revenue. The lion’s share – $47 million – will go to BOEMRE. But with less than half of what was asked for, that agency’s personnel additions, at least for this year, probably will cover only about 24 new hires, quite a bit short of expectations.

To underscore the agency’s personnel needs, Bromwich said at his OTC press conference that BOEMRE “desperately” needs more engineers, inspectors and other safety personnel, environmental scientists and employees to do environmental analysis, as well as more people to help with the permitting process.

However, the BOEMRE director, anxious to demonstrate the agency’s zeal to man its staff, also detailed his visits to petroleum engineering and environmental science schools around the country. So far, he said, the visits generated more than 1,000 job applications. To make the jobs more attractive, he has asked the U.S. Office of Personnel Management to allow BOEMRE to pay more than the normal GS-7 salary for federal employees with university undergraduate degrees.

What’s more, Bromwich earlier announced that BOEMRE has asked major U.S. producers to provide the names of recently retired petroleum engineers who might be persuaded to provide temporary service to the agency to bridge the gap as future new hires come aboard. While none of these actions has yet resulted in actual new hires, Bromwich and BOEMRE are betting on the come. Meanwhile, the quest for drilling permits for deepwater exploration remains taxing, at least, to operators and subcontractors, alike.

Existing projects

Post-Macondo, new Gulf of Mexico output has taken a heavy hit as not only deepwater exploration but also production from existing deepwater projects was shut down while BOEMRE strove to get its ducks in a row.

The result, say experts, will be a significant shortfall in annual Gulf production of both oil and gas during the next couple of years. The Energy Information Administration expects 2011 Gulf output to average 1.55 MM b/d, down 13% from last year.

Another expert energy industry observer, Wood Mackenzie, predicts the Gulf production total for this year will be down by 375,000 b/d. But by judging the glass to be half-full, optimists in the industry believe that the drilling permits granted so far will do much to help Gulf production eventually reach pre-Macondo levels.

At first, after the moratorium was announced in May 2010, some industry observers warned that offshore operators, particularly major companies, would pull up stakes in the Gulf and move their operations to other parts of the world, where fewer such hindrances existed.

The real result, however, was just the opposite – at least up to now. Most operators arranged standby deals with drilling contractors for deepwater equipment while the new rules were being drafted by BOEMRE, basing their wait-a-bit tactic on the declaration made by Interior that the moratorium would last for six months or less. However, a few operators did quit major participation in some Gulf projects, ridding themselves of rig contracts by citingforce majeure conditions.

But while deepwater permitting was resumed in February, the process was slower than expected, and some companies, mostly independents, are wondering how much longer they will have to wait to get back to work. Nevertheless, some have gone back to work, renewing development plans and standing in line for BOEMRE reviews and ultimately, permit approvals.

Deepwater development in the Gulf currently is being resumed or is set to start in a number of discovered fields. For more information on these projects, seeOffshore, May 2011, “Operators Gear Up for Gulf Operations,” p. 36.

More Offshore Issue Articles

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com