Deepwater drilling on the way off South Africa

Large untested prospects up for grabs

J. Roux • D. van der Spuy • V. Singh

Petroleum Agency SA

South Africa's offshore has never seen deepwater exploration, but new seismic data indicates deepwater drilling might be the answer to South Africa's unquenchable thirst for oil. During the past 30 years, exploration of Mesozoic basins was gener-ally restricted landwards of the 200-m isobath. In fact, only a few wells in the Orange basin on the west coast explored water depths to 400 m. Off the country's south coast, the strong Agulhas current and treacherous weather conditions restricted operations to 300 m.

A study of oil discoveries made during the 1990s indicates giant oil discoveries are more frequently found in the deepwater areas of the world compared with the shallower-water regions. It also demonstrates that 87% of deepwater discoveries are made in turbidite sandstones, which are associated with oil-prone source rocks.

Mass-flow sandstones normally consist of young (in geological terms) sediments that ensure good reservoir qualities and favorable oil production rates. Advances in technology have limited exploration risk. Improved seismic imagery and several remote sensing techniques, together with improved understanding of the geological model, have contributed to improving the deepwater drilling success rate.

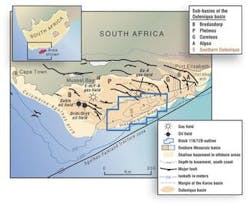

The offshore basins

South Africa's first offshore well in 1968 discovered the Superior gas field in the Pletmos basin. Most offshore exploration, however, focused on the Bredasdorp basin, leading eventually to production of the F-A, E-M, and satellite gas fields in 1992. May 1997 saw first oil production from a deep marine basin floor channel and fan complex (bff). With the addition of the Sable oil, gas, and condensate field in 2003, the offshore output has reached 40,000 b/d.

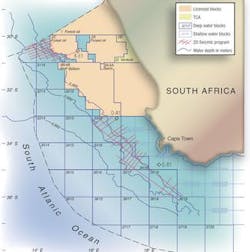

The Orange basin is defined by the extent of a sedimentary wedge that occupies 150,000 sq km off the southwestern coast of Africa and is more than 8 km thick in places. Although the basin has been sparsely drilled, with only 34 wells testing the shallow-water areas, results have been encouraging. Two gas fields (Ibhubesi off South Africa and Kudu off Namibia) with multi-tcf potential were discovered within the younger geology, while the A-J1 well yielded an oil discovery in some of the oldest sedimentary fill.

Forest Oil International has defined the Ibhubesi gas field through appraisal drilling near the original A-K1 discovery well. The tested wells in this field yielded a high combined flow rate of dry gas and condensate. Analysis of 2D and new 3D seismic data has defined many new prospects and justifies the extension of this play for some distance to the north. Eight more appraisal wells will be drilled over the next two years, and a large development of what may prove to be a multi-tcf field is envisioned for the future. This development will be a first for the west coast of South Africa.

The remaining basin, Durban, remains under-explored with only four non-commercial wells testing the near-shore areas.

The west coast

A new non-exclusive 2D survey acquired by PGS has confirmed the viability of speculative plays previously envisioned in deeper water and has revealed exciting new information that positively impacts on the prospectivity of the region.

The syn-rift succession in the area covered by the survey is thicker than expected and less isolated than the grabens inshore, while the younger sediment package is far thicker and more extensive than originally thought. It was possible to map the source rock interval across the entire data set. Laterally continuous high seismic amplitudes occur regionally in this interval, a characteristic of the seismic signature of the early Cretaceous source sequences in both the Orange and the neighboring Bredasdorp basins. This is encouraging evidence for the existence of this source interval on a basin-wide scale.

The overlying sediment wedge thins to the west and south, and models show that in these areas the early Cretaceous source sequences are likely in the oil window. Based on trends observed in boreholes drilled across the shelf and the results of the DSDP 361 scientific borehole, source rocks are postulated to improve in quality and become increasingly oil-prone away from the influence of the continental sediment-bearing river systems. The coincidence of this improvement in quality with a general thinning of the sediment wedge suggests that the deepwater Orange basin could well be oil prone.

Possible traps for oil imaged on the new data include structural, stratigraphic, and combination types. Possible structural traps occur within the large fault blocks of the earliest sedimentary succession.

In shallower water areas of 1-2 km, sediments have collapsed against fault closures, resulting in traps of billion-barrel potential. A toe-thrust province in the north also provides several opportunities for structural traps. A large number of possible traps, in the form of channel deposits and basin floor fans, were identified throughout the survey in both the Cretaceous and Tertiary.

Still in deep water, but slightly to the east in block 2C operated by Forest Oil, a new 3D seismic survey clearly shows a system of gas chimneys and crater development on the sea floor.

A structure map shows two closures west of the main fault in the area and one to the east. Some high amplitudes coinciding with the western crest of the feature suggest the presence of hydrocarbon accumulations. Water depth is 400-900 m. Possible reserves could be greater than many tens of millions of barrels of oil.

BHP Billiton operates block 3B/4B south of block 2C. Its interpretation of a new 2D seismic survey over this block has led to the identification of 10 prospects in fairly deep water. The prospects are within a number of different play types and occur at various stratigraphic levels. A new study demonstrates that the area, where the source rocks can be expected to be at the right level to produce oil, is greater than previously thought, making this area even more prospective.

null

The south coast

The deepwater extension of the Bredasdorp and Pletmos sub-basins, known as the Southern Outeniqua basin, is an untested world-class frontier area with hydrocarbon potential. Canadian Natural Resources Interna-tional acquired a 2D seismic survey of 3,700 km of data over the deepwater blocks 11B/12B in 2001. The survey confirmed the presence of large domal structures within the synrift succession along the periphery of the basin. One of the structures has an upside potential of 3-5 tcf of gas. But the most exciting revelation was a gigantic Albian age deep marine bff complex, called the Paddavissie prospect, which covers more than 2,000 sq km.

Seismic evidence of direct hydrocarbon indicators suggests the possibility of large volumes of trapped hydro- carbons within the large Southern Outeniqua basin 14A bff complex. The presence of mature oil-prone source rocks and the production from similar reservoirs nearby contribute toward making this a challenging and exciting prospect.

This prospect in deep to ultra-deep waters is gigantic with an upside potential of billions of barrels of oil. CNR is evaluating the region's potential. The next steps are to complete the amplitude versus offset studies and identify the sweet spots of lowest exploration risk. The next step is to identify potential areas for 3D seismic surveys, which would lead to the first deepwater well drilled off the southern tip of Africa. CNR plans an additional in-fill 2D survey of 3,000 km for February 2004.

The east coast

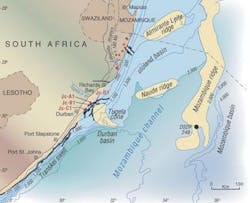

A review of the regional geology and drilling results provides compelling evidence of large untested structural and stratigraphic traps and confirmation of overlooked traces of oil in the areas' most recently drilled well Jc-D1. New studies of Jc-D1, drilled in 2000, reveal:

- Fluid inclusion studies indicate light hydrocarbons are present

- A geochemical extract from shallower sands within the well yielded biodegraded oil

- Bitumen staining and fluorescence in the lower part of the well

- A geochemical extract from the basal section of the well yielded light oil, the source of which is a marine deep-seated source rock.

Possible source rocks within the Durban and Zululand basins are a deep-seated Jurassic source within graben sediments of the basins. The Tugela fan has not been explored for hydrocarbons, but recent seismic mapping reveals extensive systems of bff complexes extending into deepwater. Numerous untested leads and prospects have been identified in synrift and the overlying shallower intervals as well.

null

The west-easterly striking seismic profile A-A across the Durban basin clearly illustrates the proximal position of the wells and the untested sediment wedge, which increases in thickness basin ward. The principal exploration targets are large tilted fault blocks and faulted anticlines, channel sands, and stratigraphic traps within basin floor fans. Several plays are evident on seismic sections. The deeper Upper Cretaceous targets comprise large four-way dip closed anticlines at break-up unconformity level. These structures are expected to contain oil and gas.

The Tiger lead lies above an upthrown basement block. Target intervals range from the Cretaceous to the Tertiary and represent more than 1,000 m of section draped over basement. Closure is demonstrated at many levels. Existing wells and sparse seismic data are inadequate for effective evaluation of the petroleum potential of this large area. There is, however, sufficient encouragement for the presence of reservoirs, traps, source rocks, and active petroleum systems to justify further exploration and the acquisition of modern seismic data.

The Tugela cone is proximal to the industrial hub of South Africa. An existing pipeline network links Durban with the Johannesburg industrial area. The Durban and Zululand basins form the southern extremity of the Mozam-bique basin, which hosts the Pande and Temane gas fields in Mozam-bique. Sasol is developing these fields, and a pipeline is under construction to supply gas to the same area within South Africa. The Tiger lead and many other untested large structures of billion-barrel upside potential could contain commercial discoveries, and these may reap the benefits of a pipeline network and an industry hungry for oil and gas resources.