New benchmarking analysis may provide needed recalibration for project cycle times

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the July-August 2023 issue of Offshore magazine. Click here to view the full issue.

By Richard B. D’Souza, Richard B Offshore LLC; and Shiladitya Basu, KBR

The success of a major deepwater capital project is significantly influenced by how well capital and schedule commitments made at the time of final investment decision (FID) are met. Front end loading (FEL) activities are the operators’ work processes leading up to FID. FEL includes reservoir characterization and appraisal, definition of the well construction program, and the facilities (production platform, subsea, umbilicals, risers, flowlines, and export systems) that process and transport reservoir fluids.

Most deepwater developments can be categorized as major capital or megaprojects, with capital costs ranging from $3 billion to $10 billion. The offshore industry’s track record for delivering megaprojects within sanctioned budget and schedule is not stellar. Project economics are seriously eroded if budgeted cost and schedule slip by more than 10%. There are many reasons for slippage, but a root cause is the inadequate allocation of contingency and availability of accurate, current benchmarking data. Operators require independent cost and schedule benchmarking of risked capital costs and sanction-to-first production (STFP) schedules, established at the end of FEL, to validate contingencies before green lighting a project.

Schedule benchmarking compares risked STFP schedule at FID to actual STFP of an analogous project in production. The fabrication, integration, transport, installation, hook up and commissioning of the floating production unit (FPU) is typically on the critical path to first production. Since the FPU topside operating weight is a key schedule driver, schedule benchmarking can be used to compare the planned STFP of the project to the actual STFP of a producing analogous FPU project, with a topside of similar operating weight and complexity.

Cost reduction imperative

After the collapse of oil prices in 2014, operators responded by focusing on cost reduction, with an emphasis on greater predictability in project outcomes. Many projects were delayed or cancelled, leading to a significant consolidation of the supply chain in response to the reduced demand for their services. An unfortunate outcome was the considerable loss of skilled labor and deepwater expertise, and a contraction of tier one contractors available to bid for major deepwater projects. In the period from mid-2014 to the start of the COVID pandemic, just five deepwater FPU projects were sanctioned at breakeven costs reportedly under $40/boe.

Beginning in 2020, two global black swan events occurred in rapid succession. The first was the COVID pandemic in early 2020, and the second was the Russian-Ukraine war in early 2022. In the ensuing turmoil, oil price volatility returned, inflation of goods and services surged, and supply chains were disrupted. Four FPU projects were sanctioned post-pandemic. Two projects scheduled for sanction in this period were deferred because of the uncertainty in predicting reasonable project outcomes.

All nine FPU projects sanctioned globally since 2014 have been, or will be, impacted to varying degrees by these events. For this analysis, STFP cycle time versus topside operating weight benchmark curves for post-2014 sanctioned deepwater FPU projects were examined and compared with the pre-2014 STFP benchmarks. We found that post-2014 STFP cycle times were considerably longer across the range of topside operating weights. It is hoped that the post-2014 STFP benchmark curves presented here will provide the industry with a more robust basis for validating risked STFP schedules, and greater schedule predictability at project sanction.

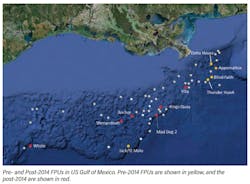

Newbuild FPUs in the Gulf

The focus here will be on six newbuild FPUs sanctioned in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico after 2014: Argos (Mad Dog 2), Vito, Whale, Anchor, Kings Quay, and Shenandoah. Only the Mad Dog 2 FPU (Argos) is a box deck configuration, the others are integrated truss decks. The Shell-designed and operated Vito and Whale FPUs are integrated truss decks with a Module Support Frame (MSF). The MSF is built with the hull and facilitates a more efficient topside load transfer to the hull. It also simplifies lifting and integration of multiple deck modules. It does require careful design of the MSF bracing to hull column connections.

There are two significant differences between pre- and post-2014 sanctioned FPUs. In the aftermath of the 2014 oil price collapse, operators were confronted with a stark choice: to sanction future deepwater developments, breakeven costs had to be reduced to $35-$40 per boe versus the $70-$80 per boe prior to the collapse. Significant cost compression was achieved by the natural deflation in the supply chain and by simplifying and standardizing designs and specifications of everything from drilling and completing wells, to subsea systems and the FPUs.

Operators focused on designing leaner and more efficient FPU topsides and hulls. The average topside operating weight of post-2014 sanctioned FPUs in the Gulf is about 15,250 mt compared with an average topside operating weight of 25,000 mt of pre-2014 sanctioned FPUs. Average FPU displacements fell from 90,000 mt to 60,650 mt.

The other major change was in contracting strategy. Seven of the eight post-2014 FPUs sanctioned globally were awarded lump sum turnkey (LSTK) EPC contracts, facilitated by the availability of larger heavy lift dry transport vessels. Only Chevron elected to stay with the traditional segmented contracting strategy employed for pre-2014 GoM FPUs for the Anchor FPU. The reasons for this shift were twofold. One was the aggressive competition by tier one Korean, Singaporean and Chinese contractors (that had made large investments to provide “one stop shop” delivery of floating platforms) for backlog as the demand for new production platforms fell off a cliff. The other was intense pressure on operators for significant capital cost reductions to meet tough economic sanction hurdles in what was expected to be a “lower for longer” oil price environment.

A brief description of each development is provided below, along with the relevant contracting strategies and impacts of the confluence of the post-2014 oil price collapse, COVID pandemic, and Ukraine war on their STFP schedules.

Mad Dog 2

BP rebooted development planning of Mad Dog 2 in 2013 when the capital cost exceeded $20 billion. The drive to reduce capital cost of the development took on greater urgency when oil prices collapsed in mid-2014 to meet a $40/boe sanction hurdle. This was achieved by reducing well count, improving well productivity, changing the FPU concept from a spar to a semisubmersible FPU (analogous to the Atlantis FPU with a box deck hull deployed earlier in the GoM), and leveraging the highly competitive drilling, construction and installation contractor market.

The project team focused on simplifying process trains and maximizing use of industry standards, without compromising safety. Employing cutting edge seismic, riser and enhanced recovery technologies enabled additional cost reduction. BP had intended to tender to the three main Korean yards only, but in early 2016 expanded the FPU fabrication bid list to include several Chinese and Singaporean yards capable of a one stop shop delivery of the fully integrated FPU and to Kiewit Offshore Services (KOS) for a conventional segmented building approach. In January 2017, after an exhaustive bid evaluation and negotiation period, Samsung Heavy Industries (SHI) was awarded a turnkey EPC contract to deliver the Argos FPU. The contract pricing structure was a hybrid of lump sum, unit rates and reimbursable elements. This was a marked change from BP’s pre-2014 GoM FPU segmented contracting strategy. SHI was completing the turnkey delivery of the giant Ichthys FPU at that time. BP sanctioned the Mad Dog 2 project in December 2016 with target first oil date in 2Q 2021, for an STFP cycle time of 52-54 months.

Hull first steel cut was in April 2018 on plan and topside steel cut was in August 2018 one month later than planned. Planned delivery of the 67,000 mt lightship weight FPU for August 2020 was delayed by five months mostly due to supply chain delays. The Argos FPU was loaded on the Boka Vanguard and dry transported to KOS on Feb. 3, 2021. The FPU arrived at the KOS on April 13, 2021, for final preparatory work and commissioning.

Subsea 7 was awarded an EPC contract to tow the FPU to the Mad Dog 2 site, install the subsea systems, umbilicals, risers and flowlines and hook them up to the FPU. Argos was wet towed to the site in September 2021 and hooked up to the twelve pre-set moorings in January 2022, and placed in service in April 2023. The Ready For Sail Away (RFSA) to first production timeframe was about 22-24 months. The JSM and Appomattox projects’ wet tow, installation, commissioning, and startup cycle times (similar in order of magnitude and complexity) were about 12 to 13 months. It is reported that issues with two production riser flexible joints during testing and availability of critical spare parts needed for topside commissioning caused the delay. The actual versus planned STFP cycle time of Mad Dog 2 is 72-74 months versus 52-54 months, with much of the delay attributable to pre sailaway commissioning at KOS and installation-related weather and equipment integrity issues during field hook up and commissioning.

Vito development

Vito is the second post-2014 deepwater development with a FPU host platform to be sanctioned in the GoM. The Vito FPU was initially planned as a replica of Appomattox, but the project was delayed by roughly three-years to reframe the development in the aftermath of the 2014 oil price collapse and attain a forward-looking breakeven price of $35/boe. The Shell team accomplished this by phasing the development, reducing well count, improving drilling efficiency, and designing a leaner FPU. Vito was sanctioned in April 2018, with first oil planned for late 2021. A turnkey contract for delivery of the integrated 22,000 mt FPU (versus 66,000 mt for Appomattox) was awarded to Sembcorp Marine. This was a radical departure from Shell’s established segmented contracting approach for a majority of their pre-2014 GoM deepwater developments. First steel was cut in mid-June and sail away from Sembcorp to the GoM planned for mid-2020.

In April 2020 Sembcorp was hit with a COVID cluster at its offshore marine and fabrication yards. Measures to contain the spread of the virus saw their operating yard workforce reduce from 20,000 to just 850, to comply with Singapore’s Ministry requirements to confine migrant workers (the bulk of the workforce) to their dormitories, severely constraining yard activities for several months. As a result, the Vito FPU was delivered to Shell in December 2021, sixteen months later than planned. The platform was dry transported and delivered to the KOS facility in late March 2022 in preparation for RFSA.

The platform was wet-towed to site by Jumbo Offshore in early summer and hooked up to its moorings. Subsea 7, the SURF EPC installation contractor, then hooked up the risers and umbilical’s leading to final commissioning. Vito came online in February 2023, which gives an STFP cycle time for Vito between 58 and 60 months, versus a planned duration of 40 months. The post-2014 sanctioned, pre-pandemic executed Appomattox STFP was 47 months, despite having a topside operating weight two and a half times greater than Vito. The 18-20 month delay is mostly attributable to pandemic-related disruptions during FPU fabrication, and partially because the Vito FPU was Sembcorp’s first turnkey EPC execution of an FPU.

Kings Quay development

In June 2018, Murphy acquired several of LLOG’s GoM assets in production and in development, including Kings Quay. At the time LLOG had already firmed up the development plan, a Delta House look-like FPU with subsea tiebacks from the Khaleesi and Mormont fields. They also had an EPC contract with Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI) for turnkey delivery of the FPU. Murphy assumed the HHI contract with minimum change orders and sanctioned the Kings Quay development in August 2019, targeting first production for the second quarter of 2022. The addition of the Samurai field reserves to the development facilitated project sanction. Fabrication of the FPU had begun in July 2019. Murphy awarded an LSTK EPCIC contract to Subsea 7 for installation and hookup of the SURF and moorings shortly after sanction.

The COVID pandemic struck five months later, and the Korean government’s enforced lockdown was swift and extreme. Murphy, in keeping with their philosophy of having a small site team, repatriated their expats, but a very good local site team was able to keep the project on track through the pandemic. The bulk of the topside integrated deck was lifted onto the hull in a single lift by a floating shear leg crane. Twenty-four months after sanction the 97% commissioned FPU was dry transported to the KOS marshalling yard, arriving in September 2021. The FPU was wet towed to the site in December 2021, hooked up to its moorings and risers, and commissioned. First production was in April 2022, 32 months after sanction, a world class performance matching that of Delta House, despite a change of operator and pandemic related disruptions. Cycle time from start of FPU construction to first production was about 34 months, an amazing feat. The FPU is currently producing in excess of its nameplate capacity.

Murphy attributed the successful execution of the Kings Quay project to a lean, experienced operator team, a good local site team, use of a standardized Exmar Opti-11,000TM FPU, HHI and operator teams’ familiarity with fabrication of the Delta House hull and associated learnings (design one build two) and awarding EPC and EPCIC contracts for the FPU fabrication and SURF/mooring installation and commissioning to tier one contractors respectively.

Anchor development

Chevron discovered the Anchor field in late 2014 in the GoM, at about the time oil prices collapsed. The reservoir is in the Wilcox formation characterized by ultra-high pressures (HP) and high temperatures (HT) that required qualification of drilling, completion, and subsea equipment. It took five years to sanction the project in December 2019, just months before the pandemic struck. To meet the tough break-even hurdle (under $30/ boe), the Anchor team opted for a staged development with an initial seven subsea wells producing to an FPU.

With a topside operating weight of 17,000 mt and throughput of about 80,000 boe, it is half the size and capacity of the JSM FPU sanctioned in 2010 but designed to accommodate future tiebacks from subsequent stages. By staging the development Chevron was able to sanction the project at $5.7 billion and de-risk it. Drilling and completion durations, and delivery of the subsea kit for the ultra-HP and HT reservoir are on near critical path to first production. Anchor is the first sanctioned deepwater ultra-HP field development. First production guidance is 2Q 2024.

The Anchor FPU is a lean-design semisubmersible that utilized expertise of the JSM design team (KBR for hull and Wood for topside), but with a truss rather than box deck, to simplify and accelerate topside integration and commissioning. Chevron bucked the post-2014 EPC trend by awarding the hull fabrication contract to Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), its first in five years, and topside fabrication, integration, and pre-commissioning contract to KOS. DSME delivered the 22,000 mt lightship Anchor hull to KOS for topside integration in the first week of October 2022. If delivered per guidance at sanction, the STFP cycle time range will be 50 to 52 months. The success of Anchor is important for the industry as it will facilitate the Sparta and Shenandoah projects and future HP/HT developments in the GoM.

Whale development

Shell announced the Whale discovery in the Alaminos Canyon, within 16 km of the Perdido development. After drilling several appraisal wells, Shell confirmed that the prospect was one of its largest discoveries made in the GoM in over a decade. It was large enough to host a stand-alone facility, despite its proximity to the Perdido Spar platform anchored in 2,600 m of water. In June 2019, Shell announced that the development would closely resemble the Vito development and would be fast-tracked.

The Whale FPU is a facsimile of the Vito hull and an 80% replica of the Vito topside (similar operating weight and nameplate capacity), using the cost reduction (simplification, standardization, repeatability) levers employed for Vito. It included retaining the same hull and topside designers and awarding an EPC contract to Sembcorp (who were fabricating the Vito FPU) in November 2019, subject to project sanction early the following year. In April 2020 Shell delayed FID to 2021. Pandemic-induced supply chain constraints and uncertain economic conditions led to the pause. Whale was sanctioned in July 2021 with planned first production in 3Q 2024 (an STFP cycle time between 37 months to 39 months). The Ukraine war that began in February 2022 added commercial and supply chain uncertainties that were not factored at sanction.

Shenandoah development

The Shenandoah discovery well was announced by Anadarko in February 2009. The reservoirs are in the Wilcox sands with shut-in pressures requiring 20 ksi equipment. Anadarko relinquished the field in 2017 after spending $1 billion to drill multiple appraisal wells due to a substantial downgrade of the initial recoverable reserve estimates, the 2014 oil price plunge, and the high cost of drilling and producing ultra-HP reservoirs.

LLOG assumed operatorship in 2018 and was granted a Suspension of Production by the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement on a commitment of a reasonable schedule leading to commencement of production. The LLOG development plan was a multi-stage development with eight subsea wells producing to a newbuild FPU, that would mimic their successful Delta House FPU, with a nameplate production capacity of 100,000 boe/d. With an eye on sanctioning the development in the first half of 2020, LLOG placed an order for two ultra-high pressure subsea trees in October 2019.

LLOG relinquished its stake in the field to Beacon offshore in July 2020. The pandemic-induced economic uncertainty was a factor in LLOG’s decision. Beacon sanctioned the development as envisioned by LLOG a year later, on Aug. 27, 2021. After a tender process, Beacon awarded HHI (the fabricators of the Kings Quay FPU delivered in July 2021), an EPC contract for delivery of the Shenandoah FPU. Beacon guidance for first production at project sanction was for 1Q 2025 (a STFP cycle time between 41 and 44 months), about 12 months longer than the Kings Quay development. The duration was largely driven by the long lead times for supply of the Transocean Hercules drillship and the 20 ksi blowout preventor capable of drilling and completing the ultra-HP wells. The added uncertainty precipitated by the Ukraine war was not anticipated when Shenandoah was sanctioned.

Benchmark STFP cycle times

A timeline for all eight (globally) FPUs sanctioned after 2014 is shown in the STFP cycle time chronology chart presented with this article. The start of pandemic-related lockdowns (March 2020) and the Russia-Ukraine war (February 2022) are also shown. Neither event was anticipated when the projects were sanctioned, and their impact on planned first production guidance was not accounted for.

The Kings Quay project was delivered as planned, despite being executed during the pandemic. The project was not materially impacted by the Ukraine war, which began after the FPUs was delivered. The Kings Quay STFP cycle time is somewhat misleading as FPU fabrication began a couple of months before sanction. It is estimated that Mad Dog 2 will have begun producing about 20 months later than originally planned and Vito will start production 18 to 20 months later than the planned date. Key success factors for the on-time startup of the Kings Quay development were the effective COVID management during fabrication and an efficient offshore installation and commissioning campaign. A majority of the Mad Dog 2 delay was the result of the installation-related weather and equipment integrity issues during field hookup and commissioning. The Vito delay was caused by the strict COVID protocols instituted in Singapore which began to ease in mid-2021. The Anchor project was sanctioned in December 2019, just a few months before the onset of the pandemic. The 50-52 month planned STFP cycle time for the 17,000 mt topside FPU project is reasonable considering technical challenges of the high-pressure, higfh-temperature Wilcox reservoirs, and the long lead delivery of critical SURF equipment. With the hull delivered as planned at KOS in October 2022, there is a good probability that actual first production will be on plan, but potential impacts of Ukraine war supply chain disruptions on the remaining sixteen months of execution to first production remain unclear.

The Whale and Shenandoah projects were sanctioned well after the start of the pandemic, but before the Ukraine war began. The 37-39 month planned STFP for the Whale development, largely a replica of Vito, and EPC delivery contracted to Sembcorp, that also delivered the Vito FPU, should bracket the range of actual first production. COVID-related delays in Singapore have eased significantly. The Ukraine war has caused supply chain delays, but suppliers are adjusting. Shenandoah, likewise, is a replica of Kings Quay using the same FPU design and EPC contractor.

Conclusions

Before a deepwater major capital project is sanctioned, an operator requires that the risked STFP schedule established at sanction be independently benchmarked. If the project has an FPU host platform, its topside operating weight is used as the benchmarking variable. From 2000 to 2014 over twenty deepwater projects with a newbuild FPU host platform were sanctioned. This period saw a steady rise in oil and gas prices and a relatively stable supply chain.

This period of stability was severely disrupted by three global events starting in mid-2014. The first was the steep decline in oil prices in mid-2014, followed by the outbreak of the covid pandemic in early 2020 and the Russia-Ukraine war in early 2022. The fallout resulted in a significant consolidation of tier one fabricators and fundamentally transformed the way deepwater projects are designed and executed. Growing competition for capital allocation from renewable energy and decarbonization projects is an added stressor to the availability of tier one fabricators for executing deepwater oil and gas projects. The consequence of these events on the post-2014 sanctioned STFP cycle times, to the authors’ knowledge, has not been adequately accounted for. The objective here is to derive a more appropriate STFP benchmark curve for post-2014 sanctioned deepwater FPU projects.

In summary, we find that the post-2014 cycle times are considerably longer than pre-2014 benchmark STFP cycle times, with the divergence increasing with increasing topside weight. It should be noted that the post-2014 sanctioned STFP cycle times are derived from a small sample of projects that are in production and will be updated as additional projects begin producing. As the offshore market for oil, gas and renewable energy projects picks up, the limited pool of tier one contractors will be further stretched resulting in longer and less predictable schedule outcomes.

Nevertheless, we believe that the post-2014 sanction benchmark STFP cycle time curves shown here will provide the industry with a more realistic schedule calibration for current and future deepwater FPU projects awaiting sanction, thereby reducing the risk of excessive value destructive schedule slippage.

AcknowledgementBased on the paper “Benchmarking Deepwater Semisubmersible Floating Production Unit Developments Sanction to First Production Cycle Times in a Post Pandemic Era” (OTC-32542), presented at the Offshore Technology Conference held in Houston, Texas, on May 1-4, 2023.

About the Author

Richard D'Souza

Vice President

Richard has an undergraduate degree in Naval Architecture from the Indian Institute of Technology and graduate degrees in Naval Architecture and Civil/Structural Engineering from the University of Michigan and Tulane University. He started his career in the oil patch in 1976 with Friede and Goldman in New Orleans, a consulting firm that pioneered semisubmersible, drillship and jack-up mobile offshore drilling units. He moved to Houston in 1978 with Pace Marine Engineering Systems a marine consulting firm and was Director of Arctic Technology. He co-founded Omega Marine Engineering in 1985 which engineered the first floating production system in the Gulf of Mexico. Aker Engineering acquired Omega in 1991 and he was Vice President of the Marine group. Under his direction Aker became the predominant deepwater engineering group in the industry and executed most of global deepwater field development and front end floating production projects involving semi, spar, TLP and FPSO platforms. He joined KBR in 1999 as Vice President of Deepwater Technology and organically built a deepwater engineering group to support execution of EPC projects worldwide. He became Director of Granherne Americas in 2004 and Vice President Granherne Global operations in 2009. Granherne is the global consulting arm of KBR and the premier provider of field development planning, process, safety, marine, subsea flow assurance and integrity management services, with 200 technical professionals in four regions. Richard has authored over 70 technical papers in field development planning, deepwater technology and floating production systems in major offshore conferences and publications. He has actively participated in numerous industry committees, panels and forums including SNAME, SPE, DOT, API, ISO, OMAE, ASME, OTC and DeepStar to promote deepwater technology and development. He has dedicated his career to training the next generation of deepwater technical professionals.