Cost efficiency underpins new Gulf of Mexico platform designs

Operators that are looking to develop new fields in the Gulf of Mexico are increasingly turning to production platforms that are more economical than in years past, and much more efficient in design.

Although the offshore industry has been slowly emerging from the downturn, caution and capital efficiency are still the watchwords of the day. Operators are reluctant to spend the money for the sort of “mega platform” they might have built 10 years ago.

Thus, the types of platforms being examined for the upcoming GoM projects that will have one – King’s Quay, Vito, Mad Dog 2, and Anchor – will almost certainly feature facilities that are smaller, lighter in weight, and with more standardized features than those in the past.

“The new mentality is: ‘Let’s design around what we know we need, and let’s not build in all these what-if’s’,” says Stafford Menard, Vice President of Deepwater Development for Audubon Engineering Solutions. Audubon recently received a contract from Murphy Exploration & Production Co. for engineering, procurement and construction support for the King’s Quay floating production system. Previously, Audubon provided design, procurement, and construction management services for the Delta House FPS, now operated by Murphy. As it did with Delta House, Audubon is using a “one-size-fits-most” standard design approach for the King’s Quay FPS.

“In the past, engineers would design a platform not only around base field requirements of the original reservoir, but they would also design for considerable future capacity,” Menard says. Items like waterflood equipment, additional compressor packages, and future tieback components were included in the design. “All these considerations would add more space on the deck and more payload capacity; this in turn enlarges the size of the hull, and then the anchoring system gets bigger. And it just kind of keeps snowballing.” But because of the downturn and continued caution with capital expenditures, “operators are no longer advancing this philosophy. That’s the big difference between then and now.”

So, designing only for the initial size of the field has become a key imperative. “Shell has done a very good job with keeping Vito lean and efficient, and LLOG did the same with Delta House and then King’s Quay, which Murphy is now in charge of. But in all these cases, the operator is focused primarily on the initial field.”

This new ‘lean and efficient’ philosophy keeps the platform space and payload down, which in turn shrinks the hull, and shrinks the needed anchoring systems. “Design engineers are now asking themselves: ‘What are the truly critical pieces of equipment?’”

Gas turbine power generators are a typical example. “Platform operations require power, so many in the industry will follow an N+1 strategy,” Menard observed. “If a platform needs three turbine generators running, we’ll put four out there. We always have one extra. And in the past, for other equipment, the N+1 philosophy was enacted. Even if it wasn’t truly critical. So operators now are really putting some thought into ‘what are the critical pieces I need sparing on?’ And it comes down to: not a whole lot. Platforms require power, and operations have to have pumps and prime movers, but aside from that, there are not that many pieces for which it’s absolutely necessary to have a spare piece,” he added. “In many cases, if a system goes down, you can work around it until you fix it.”

Operators are even beginning to take a hard look at equipment that was previously considered “critical,” such as crane equipment. “They’re not putting as many cranes on platforms as they used to,” Menard noted. “And the same rationale applies: ‘It’s nice to have three cranes but can I live with two?’ And the answer is: ‘Yes, I can live with two.’” And then anything else that operations wanted, they had to prove to the project team that it was going to pay for itself. If there was no payout, they didn’t get it.’”

In addition, the industry now has analytical modeling solutions that enable designers to explore a greater range of motion characteristics for smaller and less expensive hulls, and the smaller topsides that would be placed on the hulls. Then, informed with these analytical results, smaller and leaner platforms can be designed with the confidence that they will have the same capability to withstand various sea states as larger platforms. “We now have computing capabilities where we can model the floater in the ocean and subject it to different wave environments,” Menard says. “We can model the waves, the currents, and the wind, and the computer now does the model test in reality.” In turn, these analytical tools give the hull designers the flexibility to try different hull shapes, and modifications to shapes, and review the results before committing to any particular platform concept – all at very little expense.

Over the past several years, many of these design philosophies have been incorporated into upcoming field development projects in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico.

King’s Quay

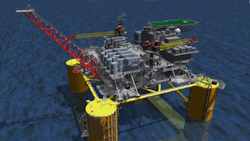

The King’s Quay project, which recently received FID, will be using a platform that closely replicates the Delta House semisubmersible platform, which began service back in April 2015. Construction of the King’s Quay semisubmersible is under way in South Korea by fabricator Hyundai Heavy Industries.

The FPS will feature a two-level topsides deck with a 10,000-ton payload, and is being designed to withstand wind and waves from a 1,000-year storm. The King’s Quay FPS facility will receive and process up to 80,000 b/d of oil production anchored by the Khaleesi/Mormont and Samurai developments in the Green Canyon area. It is expected to be in service in mid-2022.

“Delta House has been producing successfully for nearly five years,” Menard observed. “And its uptime is greater than 98%, which is excellent.” Nor is the Delta House design the largest production facility in the industry. “At about 80,000 b/d, it’s what I would call ‘midsize’,” he added. “They didn’t spend a lot of money. They just cut back on things that weren’t critical and decided that, ‘Hey, we’ll go with what we know we need, and if we need something else later, we’ll figure out how to do it.’”

Vito

Located over four blocks in the Mississippi Canyon area of the Gulf of Mexico, the Vito development will consist of eight subsea wells with deep (18,000 ft) in-well gas lift. Shell made the final investment decision in April 2018, citing a break-even price estimated to be less than $35/bbl. That decision set in motion the construction and fabrication of a new, simplified host design and subsea infrastructure.

In 2015, Shell began to redesign the Vito project, reducing cost estimates by more than 70% from the original concept. During that effort, a new and simplified design was chosen for the main production unit and related infrastructure. Shell has explained that Vito’s cost savings are due to the simplified design, in addition to working collaboratively with vendors in a variety of areas including well design and completions, subsea, contracting, and topsides design. “Vito is paving the way for other deepwater projects as it takes full advantage of industry-standard designs and lower cost development options,” said Eirik Sorgard, Vito Asset Manager.

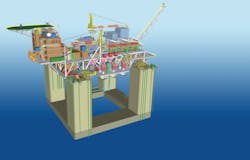

The field will be developed using a four-column semisubmersible floating production unit (FPU) weighing 39,000 tons. The FPU will consist of a single topside module and have a production capacity of 100,000 b/d of oil and 100 Mscf/d of gas. The Vito host will be located at a water depth of 4,000 ft (1,220 m) in the Mississippi Canyon block 984 in the Gulf of Mexico, 150 mi (241 km) south of New Orleans.

Shell contracted Jacobs Engineering Group to carry out the detailed engineering and front-end engineering design (FEED) studies for the topsides of the Vito FPU. Shell executed a contract with Sembcorp Marine subsidiary Sembcorp Marine Rigs & Floaters for the construction of the hull and topsides, as well as the integration of the Vito FPU.

The Vito development is owned by Shell Offshore (63.11% operator) and Equinor USA E&P Inc. (36.89%). Vito will be Shell’s 11th deepwater host in the Gulf of Mexico and is currently scheduled to begin producing oil in 2021.

Mad Dog 2

Meanwhile, work is under way on the design and engineering of Argos, the production platform for BP’s revamped Mad Dog 2 project. Argos will be a semisubmersible platform with the capacity to produce up to 140,000 gross b/d of crude oil through a subsea production system from up to 14 production wells and eight water injection wells.

After the cost estimate of an initial design reached more than $20 billion, BP, BHP Billiton, and Chevron embarked on a recycle of the Mad Dog Phase 2 project in 2013. Three years later, the co-owners and contractors produced a simplified and standardized platform design that reduced the overall project cost by about 60%.

In December 2016, operator BP sanctioned the leaner $9-billion project. At that time Bob Dudley, BP Group CEO, said: “This announcement shows that big deepwater projects can still be economic in a low-price environment in the US if they are designed in a smart and cost-effective way.”

Bill Steel, project general manager, Mad Dog Phase 2, BP, said that the initial second phase called “Big Dog” was an all-in strategy that aimed to develop all the resources. He said the reevaluation delivered a competitive solution by incorporating value over volume, industry learned solutions, and collaboration.

According to Steel, two-thirds of the cost savings came from re-engineering the floating production system to a simplified and optimized semisubmersible production platform and using all subsea wells; and one-third came from industry collaboration and standardization.

The hull and topsides of the Argos platform are currently under construction in South Korea. Samsung Heavy Industries (SHI) won a $1.27-billion contract to build the floating production unit. SHI awarded Wood plc (then Wood Group) an $80-million contract to provide detailed engineering and procurement services for the topsides.

First oil is expected in late 2021.

The second Mad Dog platform will be moored in the Green Canyon area about 6 mi (10 km) southwest of the existing Mad Dog platform, which is in 4,500 ft (1,372 m) of water about 190 mi (306 km) south of New Orleans.

The platform will be the first new BP-operated production facility in the Gulf of Mexico since 2008, when Thunder Horse came online. It will be the company’s fifth operated platform in the Gulf of Mexico, and the company says that it will help extend the life of the super-giant Mad Dog oil field beyond 2050.

Automating deepwater operations

Another key component in reducing platform construction costs is reducing the number of persons onboard (POB). “Both Vito and Delta House have reduced the POB number,” Menard notes. “And a number of operators are now taking a step back and saying: ‘Do we really need all these people offshore?’ Just like equipment. They’re looking for what is the absolute number of people they need to operate, and thinking ‘Let’s not have non-essential people out there.’” In addition, Menard notes that with people onboard, platforms need quarters, and that drives up costs on several fronts – not only the additional structure, but also the need for life support equipment, such as, firefighting, water, sewer systems and other utilities. “It’s still incremental in the Gulf,” Menard notes, “but operators are beginning to ask: ‘Do we really need a 120-man quarters? Can we get by with 80, or 50?’ Operators are becoming much more innovative and developing systems to operate with fewer.”

This line of reasoning then begs the question – do the production facilities need to have anybody permanently stationed onboard? “So now the operators are asking themselves: ‘Are we not technologically advanced enough to operate these systems from our office/onshore control facilities? Can we not remotely control these platforms?’ And the answer is yes, we have unmanned platforms on the shelf. And they’ve been out there for many years.”

The big question, Menard observes, will be on floating facilities in deepwater. Currently, the US Coast Guard regulates manning requirements on floating hulls. “In the past, they have always insisted that producers have someone on a hull. But that is changing. In the future, both operators and regulators may be more accepting of normally unmanned installations, or NUIs.” If this technology gains broader acceptance in the future, it will have a further cost reduction effect, making deepwater platforms in the Gulf of Mexico safer and more cost effective, and therefore more competitive with lower cost onshore energy production. •

About the Author

Bruce Beaubouef

Managing Editor

Bruce Beaubouef is Managing Editor for Offshore magazine. In that capacity, he plans and oversees content for the magazine; writes features on technologies and trends for the magazine; writes news updates for the website; creates and moderates topical webinars; and creates videos that focus on offshore oil and gas and renewable energies. Beaubouef has been in the oil and gas trade media for 25 years, starting out as Editor of Hart’s Pipeline Digest in 1998. From there, he went on to serve as Associate Editor for Pipe Line and Gas Industry for Gulf Publishing for four years before rejoining Hart Publications as Editor of PipeLine and Gas Technology in 2003. He joined Offshore magazine as Managing Editor in 2010, at that time owned by PennWell Corp. Beaubouef earned his Ph.D. at the University of Houston in 1997, and his dissertation was published in book form by Texas A&M University Press in September 2007 as The Strategic Petroleum Reserve: U.S. Energy Security and Oil Politics, 1975-2005.