Dispersants could worsen Atlantic Margin spill clean-up, researchers claim

Offshore staff

EDINBURGH, UK – A deepwater oil spill in the northeast Atlantic Ocean would be more difficult to contain than the Deepwater Horizon spill of 2010, according to new research by Heriot-Watt University.

Operators typically apply dispersants to break up the oil in order to encourage it to degrade naturally. In the Faroe-Shetland Channel, however, this could lead to the formation of marine oil snow (MOS).

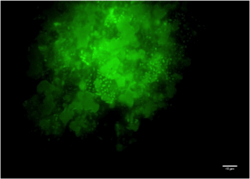

MOS comprises sticky, floating organic particles that contain oil droplets from spills. MOS sinks quickly, causing much of the oil to disappear from the sea surface. Observers may think the spill has been cleaned up, but in fact the oil has been carried to the seabed, with potentially damaging effects on deep sea ecosystems.

The rapid sinking of large volumes of MOS to the seafloor led to the “dirty blizzard” that occurred during theDeepwater Horizon spill, the university’s research team found, and may have also accounted for vast quantities of oil that impacted much of the continental slope in the northern Gulf of Mexico around the Macondo wellhead.

Dr. Tony Gutierrez, associate professor of Microbiology at Heriot-Watt, said: “The Faroe-Shetland Channel is at the frontier of deepwater petroleum exploration, so there is a pressing need for fundamental research in this region. The area is already home to rigs that are extracting oil at depths of down to 500 m [1,640 ft], and the region is being scoped for oil at much greater depths.

“The Faroe-Shetland Channel is the ‘spaghetti junction’ of Icelandic, Norwegian, and Atlantic currents and is much more hydrodynamic than theGulf of Mexico, where the Deepwater Horizon spill occurred.

“The possibility of a deep sea spill in this area in the future cannot be discounted, so it’s vital we know how to respond.

“Our research is a first step to understanding the fate of oil in the event of a major spill in the Faroe-Shetland Channel. We don’t know exactly what happens when the MOS arrives on the seabed, but given the fragility of sponge belts in the Faroe-Shetland Channel and other sensitive benthic communities, it’s not likely to be good.”

Laura Duran Suja, a PhD student at Heriot-Watt who led the study, took surface seawater samples from the Modified North Atlantic Wester water mass near BP’s Schiehallion oil field, and incubated these with the oil under conditions simulating the sea surface.

Over the course of six weeks she studied the microbial response, including of the oil-degrading bacterial communities, and observed build-up of MOS in incubations treated with dispersant and/or nutrients.

Dr. Gutierrez said: “The good news is that the MOS harbors rich communities of oil-degrading bacteria, which have an important role in ‘eating’ up the oil.”

However, he cautioned that more work was needed to understand existing dispersants and to develop safer, more effective oil-spill solutions that minimize the impact on pelagic and benthic ecosystems in the area.

04/12/2017