Modern offshore fleet comprised of same rig types as in the 1950s

Jackups the most numerous, but besides deepwater floaters like drillships and semis, the global rig inventory embraces submersibles, inland barges, even tender-assisted rigs

Some might observe that the drilling rig fleet in today’s global offshore oil and gas industry is a far cry from that of the 1950s, when the industry really got up and running. In one sense, they’d be correct. But according to information in the Offshore Energy Center (OEC)’s new book,Pioneering Offshore: The Early Years, in another sense they’d be wrong.

In the early years, existing rig types, along with their water-depth capabilities, included inland barges (to 10 ft), drilling tenders (to 40 ft), submersibles (80 to 100 ft), drill barges (to 120 ft) and self-elevating, or “jackup” units (to 150 ft). All were supported on the bottom when drilling. The opening chapters of the new OEC book detail the evolution of mobile offshore drilling and the rig types that sprang from it.

This rig fleet makeup remained about the same through the 1950s. But in the early 1960s, the book points out, ship-shaped drill barges; self-propelled drillships and semisubmersibles arrived on the scene. Most of these new floating rigs were designed for drilling off the U.S. West Coast, where water depths plummet past bottom-supported rig limits only a short distance offshore.

But even today, perhaps surprisingly after 60 years, the offshore rig fleet continues to consist of all the abovementioned rig types, either working, stacked or under construction. In most cases, however, the drilling water depth capabilities of the rigs have been much increased.

By rig type, the most numerous rigs today are jackups (478), followed by semisubmersibles (210), drillships (56), drill barges (48), tenders (29), and submersibles (7). What’s more, there are 88 inland barge rigs and a total of 255 self-contained platform rigs, which, while not considered “mobile” units, nonetheless drill development wells from fixed and floating offshore structures.

In the early days, everything offshore seemed new and unspoiled, the book points out. What’s more, creative oilmen were responsible for the rig designs.

Escaping from the tender ‘trap’

Following Kerr-McGee’s success with their naval-surplus YF barge cum tender-assisted platform unit,Rig 16, other producers entered the offshore arena and enthusiastically hopped aboard the mobile drilling rig bandwagon. By 1954, the book notes, some 22 tender-supported rigs - most of them newly built, rather than surplus craft with modifications - already were in service, and an additional six were under construction.

But while somewhat mobile, the tender-type rigs were still slow to move, the book notes.

“As more producing companies entered the Gulf offshore picture, they recognized that using even tender-assisted fixed platforms for exploratory drilling remained time-consuming and expensive. Most agreed that to drill exploration wells more cost-effectively, they needed rigs that could move much more quickly from well to well, preferably without need for a fixed platform - at least not until they made a discovery. In short, the industry needed a more mobile mobile unit.

“They found the beginnings of such a rig back in the transition zone.”

The Hayward touch

In 1947 John T. Hayward, a marine engineer working for a Tulsa, Oklahoma based producing company, Barnsdall Oil & Gas, was asked to bring Barnsdall, which held some leases with others in Breton Sound off the Mississippi coast, into the offshore industry. They needed a technology advancement to do so, financial advisors said.

Giving the idea long thought, Hayward in time came to believe the company should build its own mobile offshore drilling unit - a revolutionary one. To produce such a rig, the book notes, Hayward envisioned combining the best features of inland barges with those of piled platforms to create a single, portable, and stable unit, which eventually was dubbed the “submersible” rig.

“Hayward’s design was, in fact, a barge hull connected to a separate drilling deck by a series of supporting columns (referred to in offshore jargon as ‘posts’). Even when submerged, the height provided by the posts left the drilling deck high and dry. This eliminated the rocking effect caused by storm-amplified waves, since much of their force passed harmlessly through the space between the barge and the drilling deck.

“However, this submersible barge rig design also provided some significant lagniappe (Creole French for ‘a little something extra’). Workers could empty the buoyancy tanks and re-float the barge hull, making it a truly mobile drilling unit.”

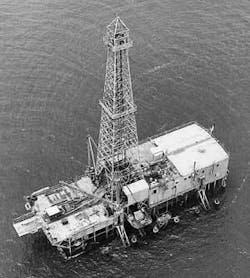

The rig, christenedBreton Rig 20, went to work on the Breton Sound prospects immediately after construction at a coastal shipyard. Its successful drilling in up to 20 ft of water put the rig in high demand by other operators (Figure 1). However, the rig’s official name didn’t stick, and it came to be referred to as the “Hayward-Barnsdall Rig,” even after Kerr-McGee bought it in 1951 and named it Transworld Rig 40. In any case, the book points out, the rig worked steadily until it was retired from the fleet in 1968.

Three-year breather spawns Mr. Charlie

Meanwhile, a three-year delay of new lease sales in the Gulf had begun in 1950, stemming chiefly from the unanswered question of whether the federal or state governments controlled submerged lands off coastal states. This brouhaha, known as “the Tidelands Controversy,” described in great detail in the book, was settled in 1953 when the U.S. Congress passed laws granting coastal states jurisdiction over the first three miles off their low-tide shorelines. Texas and the west coast of Florida received a larger jurisdiction - 3 leagues (10.35 miles) - granted them by the federal government in the 19th century when they became states.

“So, coastal states had gained a victory of sorts. They received stewardship over sizeable chunks of marine acreage, although most coastal states elsewhere on the continent had little apparent offshore oil potential. In the end, the federal government benefited most by dint of the industry’s incessant hankering to push into deeper water farther offshore, beyond even state limits.”

Resumption of lease sales resulted in operators’ interest in offshore acreage moving farther out to sea and thus, into gradually deeper water. To seize the advantage presented by this, says the book, a Kerr-McGee employee, Alden J. “Doc” Laborde, left the company in 1953 in an attempt to raise the money necessary to build a new submersible rig type with deeper water depth capabilities. Laborde, a Naval Academy graduate and U.S. Navy veteran, pictured a larger and better version of the Hayward-Barnsdall rig that could handle year-round weather conditions in the open Gulf.

After failing to gain the interest of traditional offshore producers in helping to finance the rig, Laborde shifted emphasis to a proposal for an oil company to finance formation of a contract drilling company that would operate the rig for them as well as for other operators. The idea worked, and a mid-sized independent operator, Murphy Oil Co. of El Dorado, Ark., agreed to finance the brunt of the estimated construction cost of $2 million.

“’Only when I went inland (to Arkansas) to people totally unfamiliar with the ocean environment was I able to convince anyone of the technical and commercial possibilities of my proposed gamble,’ Laborde later said.”

He managed to find investors to fill out the rest of the required capital and formed a new company, Ocean Drilling & Exploration Co. (Odeco). The rig, when completed in a New Orleans shipyard, was christenedMr. Charlie after Charles Murphy, board chairman of Murphy Oil (Figure 2).

“Laborde contracted to drill several wells for Shell and quickly mobilized the rig to its first drill site in the South Pass Area near the Mississippi River’s finger-like routes into the open Gulf. At the first location, the water depth reached 40 ft - the rig’s full capacity.

“There, even though storm-generated wave action jostled the submerged rig away from the well center several times, Mr. Charlie performed to Shell’s apparent satisfaction. Laborde didn’t know it at the time, but when Shell ran electric logs of the first well - whose resulting data was so secret that even he was asked to leave the rig while they were collected - they confirmed the presence of a significant oil reservoir.”

Bottle rigs presage floaters

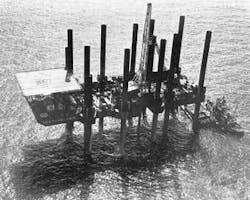

Meanwhile, the generally rectangular-shaped submersible rigs continued to catch on. But they were soon replaced by the ultimate submersible - a column-stabilized, or “bottle”-type rig, which abandoned the rectangular design for a more squared-off, or in some cases even triangular, shape (Figure 3).

In 1956, the book notes, Kerr-McGee built itsRig 46, the first of the bottle-type rigs.

“At the rig’s bottom, a grid pattern of horizontal, cylindrical members connected four large, widely spaced, cross-braced vertical columns, each of which narrowed at the top, much like the neck of a bottle. The columns supported the main deck, on which rested the drilling rig, machinery spaces, and crew quarters.

A number of contractors subsequently designed and built their own versions of the bottle-type submersible, some of which are detailed in the book. Ultimately, however, they extended the bottle rig’s water-depth capability to between 125 ft and 175 ft. The concept was so successful for such water depths that many continued to work as development drilling, well completion, and workover rigs until the 1990s.

“The bottle rig story all but ended in 1963 with Kerr-McGee’s Transworld Rig 54, the largest and one of the last of its type ever built. Eventually, even Rig 54’s capabilities became limited as water beneath new leases deepened - and perhaps more notably, as a number of new rig designs overtook the industry…Once resting on bottom, Rig 54 could drill in up to 175 ft of water, yet still provide a minimum main deck clearance of 25 ft.”

While submersibles affordedoperators with the abilityto develop acreage off Louisiana and Texas, the high success rate of offshore drilling compelled producers to seek equipment rated for even greater water depths, says the book. They also sought rock-solid rig stability for drilling in deeper water, where even routine waves and currents were strong enough to jostle most submersible barge hulls off station. The submersible had a definite water depth limit.

Faster mobility jacks up rig fleet

Several companies investigated the concept of installing “legs” on rigs, which could be lowered to the bottom and then “jacked” downward even more to elevate the entire barge and drilling deck above the water’s surface. This jackup idea was a rather old one, the book points out, having been used since the 1930sto provide stable yet mobile offshore docks for various marine construction projects. Allied forces off Normandy had used variations of such docks during the D-Day invasion of Europe in 1944, for example.

But the mobility factor was what exploration and field development drilling specialists liked most about the jackup dock, says the book, and in 1950, Col. Leon B. Delong - credited with coming up with the most workable jacking design to that time - built several self-elevating platforms for radar towers in about 60 ft of water off the U.S. East Coast.

DeLong devised a powerful pneumatic “airbag gripper” jacking system that could lower “legs” made from tubular piles, to the sea bottom, and then further hoist the unit’s barge-type hull above the surface. According to the book’s author, the idea was that once they had served their purpose, such self-elevating platforms could be jacked down and redeployed. Although the towers were built for national defense, the mobility of such structures was music to the ears of offshore operators.

“In fact, Magnolia gave the jack-up barge its first petroleum industry dimension by redesigning a six-legged DeLong-type dock into a temporary offshore production platform. In 1953, the company installed it in the Gulf in 30 feet of water, but apparently disregarded the mobility factor, locking the platform permanently in the raised position.

By 1954, several new marine drilling contractors incorporated the DeLong concept into jackup barges equipped specifically for drilling. These included The Offshore Company’sRig No. 51 (Figure 4) and Glasscock Drilling’s Mr. Gus, both of which were used successfully to drill wells in up to 100 ft of water. Jackup rigs had an almost immediate appeal to offshore contractors.

Shipyard designs satisfy jackup buyers

Meanwhile, says the book, the Gulf Coast shipbuilding fraternity reacted positively to offshore rig construction. The shipbuilding division of Bethlehem Steel Corp., for example, with a large shipyard at Beaumont, Texas, and the R.G. LeTourneau Co., an earthmover manufacturer based in Vicksburg, Miss., among others, both patented jackup rig designs, which they marketed to the fast-growing new breed of offshore drillers.

In 1956, the LeTourneau company delivered its first jackup - theScorpion - to a start-up contractor, Zapata Off-Shore Co., founded by George H.W. Bush, who later entered politics and went on to become President of the United States. Subsequently, Zapata and others ordered more LeTourneau rigs, each with new design elements that increased the rigs’ water depth rate. Bethlehem’s mat-supported jackup design also became popular, and a number of their units - each designed for increased water depths - were ordered by new contractors.

In the ensuing years, other shipyards and naval architects designed new self-elevating rig types. By the 1980s, jackups were being fabricated all around the world, with water-depth capabilities increased in increments, as required. Some jackup rigs now working or under construction can drill in up to 400 ft of water.