Offshore at 60: Remembering the Blue Water project

Jason Theriot, Ph.D.

Jason P. Theriot Consulting, LLC

After more than three decades of toiling through the marshlands of coastal Louisiana, by the 1950s and 1960s the oil and gas industry moved its operations out into the open waters of theGulf of Mexico.

While the offshore industry dealt with new technological challenges and the increasing demand for oil and gas, it also had to contend with the new environmental regulations promulgated in the early 1970s. This shift in values and policies influenced changes to governmental oversight of development activities and to the industry's environmental planning.

The pace of offshore development accelerated throughout the late 1950s and into the 1970s, when new technologies and vast acreages of offshore leases became available. But a series of environmental disasters and pollution concerns encouraged new regulations, forcing industry and government to implement new policies on offshore safety, spill prevention, and environmental protection. The new environmental standards impacted the way industry conducted its activities both offshore and in the coastal wetlands. Managing risk now included managing environmental impact.

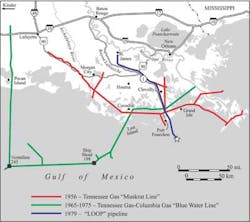

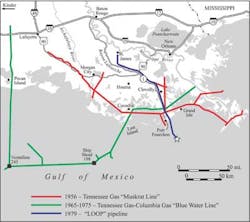

Dozens of major new offshore pipeline systems emerged during this era of expansion and environmental regulation. The Tennessee Gas-Columbia Gulf Blue Water project was built between the 1960s and the 1970s and became one of the GoM's largest natural gas-gathering systems. Its history offers clues about the challenges industry faced in the new offshore realm, and how companies and government agencies responded to new pressures and mandates to balance energy development with environmental protection.

The race for offshore gas

The 1960s proved to be an important decade for advances in offshore technology. Historic lease sales in the Gulf answered the call of growing petroleum demand, and especially for natural gas. Federal regulators pushed the industry to rapidly develop these new resources offshore. The OCS lease sales in the early 1960s opened up new tracts in undeveloped federal offshore lands. Pipeline companies then rushed to extend their pipeline systems farther offshore than ever before and also expanded the onshore pipeline network and facilities to support the development of offshore natural gas.

In the early 1960s, Tennessee Gas, one of the nation's leading natural gas companies, delivered nearly a trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas a year to its customers, most of whom resided in the northeastern United States, through its Gulf Coast pipeline system. Growing demand for natural gas from that region necessitated the search for new reserves offshore. By the mid-1960s, Tennessee Gas, which became a division under the parent corporation Tenneco Inc., had acquired additional reserves offshore through federal lease sales and outright purchases of gas-in-place. These reserves, roughly 1 tcf, were located in the prolific OCS Zone 4, a federally designated boundary that extends out to 600-ft (183-m) water depth, where the OCS ends and the seafloor drops sharply into a great abyss several thousand feet deep (the modern-day deepwater). To reach these reserves, Tennessee Gas had to build a pipeline system into areas offshore where no pipeline had yet been installed. Other competing companies also had similar ambitions and imperatives to find more gas offshore to supply America's growing demand.

The reserves in this prolific offshore zone lay just beyond the limits of existing pipeline facilities. Extending these offshore pipelines and necessary gathering platforms involved innovative equipment, high costs, big risk, intensive planning, and government approval. Companies often joined forces to spread the risk and cost.

In 1965, a group of 17 oil and gas companies led by Shell Oil created the Red Snapper Pipeline Co. That year the group applied to the Federal Power Commission (FPC), the leading regulatory agency overseeing interstate gas transportation, to build a massive pipeline superhighway that stretched across Zone 4 to gather gas from nearly a hundred new fields. The proposed $127-million "Red Snapper Line" consisted of 285 mi (459 km) of 30-in. main line that ran parallel along the shelf, 50 mi (80 km) offshore in 150 ft (46 m) of water.

Tennessee Gas, which owned reserves in various sectors throughout Zone 4, sought to build its version of a main pipeline extension to its offshore properties ahead of the Red Snapper Line. The $31.8-million project consisted of a 26-in. mainline system that stretched 80 mi (129 km) out into the Gulf, "like a finger," farther than any other pipeline at the time. For two years, Tennessee Gas and the Red Snapper group battled for the right to build this first major offshore pipeline system to reach the edge of the OCS. Meanwhile, the emergence of an environmental consciousness throughout parts of the country laid the groundwork for major environmental reform that would ultimately change the rules for new energy projects, particularly those in coastal and offshore waters.

Tennessee Gas capitalized on its leading position in the Gulf and looked beyond the "finger" line to lay the groundwork for a much larger system – the Blue Water project. This major joint venture of Tennessee Gas and Columbia Gulf, which ultimately beat out the Shell Oil-led Red Snapper project, evolved into one of the largest natural gas-gathering systems ever constructed offshore Louisiana, transporting more than 1 bcf/d of gas for American consumers over several decades.

The planning and construction phases of the Blue Water project spanned several years. Tennessee Gas completed the first leg of the system in 1968, and finished the second phase in the early 1970s during the early era of environmental regulation. In those intervening years, a series of environmental events and new laws changed the course of the industry's history and created new challenges for pipeline and E&P companies.

In the post-World War II era, as demand for energy increased, the need to increase domestic petroleum supplies spurred the technological push for expansion offshore. By the late 1960s, the Blue Water project had reached farther out into the Gulf than any other pipeline system. Tennessee Gas and others moved quickly from the coastal marshes to the OCS with few regulatory requirements regarding environmental impacts onshore or offshore. The pace of development did not slow under new environmental reforms of the 1970s; however, the traditional attitudes and "old way" of planning projects and building pipelines in sensitive coastal areas had to change.

Displaying 1/2 Page 1,2, 3Next>

View Article as Single page