Caution, capital realities to drive deepwater GoM operations

Bob George

Neil Abdalla

Cecilia Jing Cui

Gaffney, Cline & Associates

Significantly reduced cash flow for companies in 2015 means reprioritized spending is inevitable. In the short term, there is not always the flexibility to make decisions based solely on fundamentals, and so the first impacts may well include projects that in the long run remain viable. As a high cost environment, the deepwater Gulf of Mexico (GoM) would appear to be vulnerable and, indeed, cuts should be expected.

However, economic analysis by Gaffney, Cline & Associates (GCA) suggests that good projects in that environment can still be viable down to $60/bbl oil price. Further, economic rationality would suggest that where the opportunity exists, onshore shale spending would be a better short-term target for capital deferral because operating flexibility allows any adjustments made there to be reversed in equally quick order. That is not the case in the deepwater GoM where it is tomorrow's expected price that is the key driver, and where deferral now may mean missing out on gains later.

With oil now trading well below $70/bbl from a 2014 high of $115 in late June, the price slide has been the longest continual month over month decline and the steepest drop since the recession of 2008 during the financial crisis. Along with the decrease in prices, oil companies have watched 10% or more wiped off their market capitalization. The fall in oil prices is raising questions as to what impact this is going to have on industry activity in 2015. The key take-away from the recent OPEC meeting is that, through its impact on activity and therefore production, price is the weapon of choice to address the changing balance of supply in a demand-constrained world.

Activity is driven by a combination of factors: fundamental economics, cash flow and availability of funding, internal project resourcing (people), and commitments already undertaken. When there is rapid change, it takes a while for the dynamics of this mix to unwind. Looking at the other end of the spectrum, it was four or five years before the oil price rise that started in 1999 was taken to represent a paradigm shift. The initial response was for companies to prosper, pay down debt and buy back shares, "not squander it this time," and be content in the belief that price would revert to the $20/bbl mean that it had over the previous 20-25 years. On the other hand, when the oil priced crashed in 2008, it was only a few months before the response was seen in the rig count; a time lag that is now similar to when prices started falling this time around.

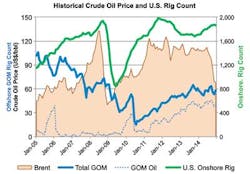

In 2008, the oil price fell below $90/bbl and the US onshore rig count was down by 1,000 within six months, although then rising again almost as rapidly as prices recovered. Thus far, in 2014, the oil price has fallen by a little less than $50/bbl from its June high, with further uncertainty as to exactly where it is headed and for how long. Nonetheless, if 2008 turns out to be a guide then a fall in the order of 500 rigs or more (some 25% to 30% of the rig count) could be the consequence, even though the rig count has only just started to hint at such a fall.

Using 2008 as a guide for 2014 is more complex in the GoM as activity at that time was dominated by gas well drilling, and the price of gas which continued falling after oil prices picked up. Since 2010 (with the hiatus following Macondo) GoM activity has been driven by drilling for oil and deepwater. The problem currently is the uncertainty as to where prices eventually settle, and for how long. There has been some suggestion that support might come in at around $60/bbl, although there has been a jump in options trading for December 2015 at $35-40/bbl. In 2009-2010, the oil price recovery was into the $70-80/bbl range until the Middle East unrest drove it higher, where it has largely remained until the current fall. Regardless, it is clear that nothing is presently certain and in terms of 2015 decisions will still need to be taken whether $70/bbl or less turns out to be a temporary phenomenon or not.

Combining the need to address cash flow but not over-react, the focus is likely to be where the impact is more easily reversible should the current price plunge reverse in whole or part. However, not all decisions will be choices; commitments already entered into will drive actions. Short-term revenue protection from hedging will allow a few months or a year or so for some activity to continue where otherwise cash flow realities might make any decision moot. For some companies, in an otherwise healthy position, the fall in prices might actually represent an opportunity, whether to press ahead with an acquisition or a project that might now cost less as construction and manufacturing constraints disappear and costs adjust accordingly.

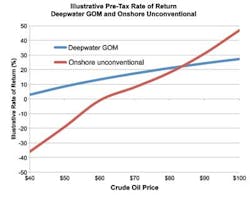

Costs, investment levels, and returns for individual companies in the deepwater GoM can be comparable with the unconventional, even though the life cycle of each of these types of development projects is quite different. The analysis conducted by GCA compared the expected rate of return (ROR) of two investment scenarios – one in the deepwater GoM, and the other in onshore unconventional shale resources. In both scenarios the capex over the lifecycle of the investments amounts to about $1 billion. While the onshore project outperforms the deepwater GoM at higher prices, at less than $80/bbl the deepwater GoM is the more attractive unit. It becomes marginal or uneconomic at less than $60/bbl.

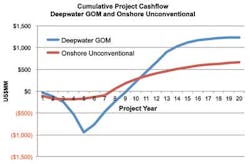

Another difference is the manner in which capital investments are made. In the GoM project, much or all of the $1 billion capital will be committed and spent perhaps five years before any cash starts flowing back. What is critical then is not the price of oil in 2015, but the price of oil in 2020. From a decision-making perspective, that means the expected price of oil in 2020 and the risk that it may be something different when 2020 arrives. Projects under way are unlikely to be stopped. Exploration in 2015 is the 2018-2020 investment project, and halting exploration prematurely may mean not having the next project to take advantage of a stronger price environment at a later time.

In the onshore unconventional shale investment, decisions can be much more short term. Drilling can be cut back, or ramped up, in fairly short order. GCA's analysis found that the $1 billion of capital may in fact be only $100-200 million of exposure, depending on the drilling intensity being undertaken, and this can be adjusted to accelerate or decelerate as market and corporate circumstances dictate.

The data suggest that it is possible for deepwater GoM projects to be viable above $60/bbl, which suggests that for the medium term, even if prices were to stay around mid-December 2014 levels, there is sufficient incentive for ongoing activity without the benefits likely to accrue through cost reduction initiatives. However, the extent of longer-term activity relative to that which has arisen following three to four years of generally $100-plus/bbl is still going to be affected by where future oil prices appear to be settling, and the extent to which the industry is able to address cost inflation that has arisen in that same time window.

The range of companies in the onshore unconventional and deepwater is quite different. Onshore has a huge mix of players from small independents to majors, and the former are going to be driven heavily by having to address their financing needs. On the other hand, deepwater GoM is the preserve of the large independents and majors for whom it is more an issue of capital allocation than financing. Thus to preserve value for the future suggests that companies with both asset types in their portfolio onshore unconventional projects will be preferentially be deferred, where other factors do not prevail.

The start of 2015 is therefore likely to be driven by a combination of caution and capital realities. Both fundamental economics and the flexibility of US unconventional development – relative to offshore operations – suggests that this will be the focus of cost reduction. Activity within the GoM will be more heavily influenced by perceptions of the medium- to long-term oil prices, and any changes in activity levels are expected to lag behind those experienced in the unconventional shale and tight oil plays.

The authors

Bob George is an executive director and senior strategic advisor with more than 40 years of experience in the international oil and gas industry. He participates in and manages GCA's advisory activities relating to financial, strategic assistance, government policy as well as expert opinion and testimony.

Neil Abdalla is a geoscientist with experience evaluating, and modeling conventional and unconventional reservoirs. His recent focus has been on field development strategies, due diligence, asset evaluations/valuations, and reserve evaluations for unconventional reservoirs. He graduated in 2012 from Penn State University with a BS geosciences degree and expects to graduate in 2014 with a MS in geology from the University of Houston.

Cecilia Jing Cui specializes in economic, financial, and fiscal analysis on oil and gas business entities, with recent work focusing on North American unconventional resources. She graduated Magna Cum Laude with a BA in mathematics from Agnes Scott College, Georgia, and obtained a MS in economics from the University of Texas.