Ultra-deepwater elephants: Giving way or marching ahead?

Jon Fredrik Müller

Rystad Energy

The OPEC resistance to reduced production quotas has spurred a continued oil price drop, following the trend from this past June. With Brent oil prices currently at $70/bbl, how robust are deepwater and ultra-deepwater developments? Will ultra-deepwater costs related to water depth, drilling time and other complexities favor the deepwater developments, or will the sheer size of ultra-deepwater elephants wrestle through to development no matter what?

At the time of writing, OPEC had just completed its 166th membership meeting and conveyed to the world that it is not reducing its quotas from the current level of 30 MMb/d of oil. The market responded by sending the oil price further down; currently it is trading around $70/bbl (Brent). The market has dropped close to 40% from June 2014 because of the surging US shale oil supply and weaker global demand prospects, which is causing an over-supplied market. Prices may continue to slide as the market realizes that the price level where US shale production growth stops is lower than $60/bbl (on field level).

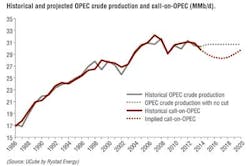

In our baseline scenario, the need for OPEC's crude production declines to a low of 28.3 MMb/d in 2017 compared with an estimated September production rate of 30.7 MMb/d. In a scenario where OPEC crude production is kept at current levels, given our assumptions for global oil demand and production from the rest of the world, the oil market would become increasingly over-supplied in the next few years.

Stock builds/draws are often mentioned in periods with over/under supply, but such a large build of inventories over several consecutive years would not be realized as global oil inventories will not be able to absorb these projected excess volumes. Oil demand would have to rise much faster than expected to prevent either a supply response or lower prices – barring any major unforeseen supply disruptions. So, either the oil prices "collapse" and the imbalances will self-correct over time, or supply growth will pre-emptively have to be meaningfully reduced (by OPEC and/or others).

The forecasted oversupply will have a different effect on different sources of production. To understand the potential impact on deepwater (500-1,500 m/1,640-4,920 ft) and ultra-deepwater developments (1,500+ m) we first need to look at history.

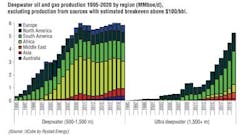

Developments deeper than traditional shelf (125 m/410 ft) began in the mid-1970s with developments off the coast of United Kingdom and Norway, and with other regions following from the early 1980s. However, developments in waters deeper than 500 m did not really commence until the late 1980s. It was in the mid-1990s that production from 500+ m really ramped up, led by developments in the US Gulf of Mexico (GoM) and Brazil. From the middle of the 2000s Africa stepped up to the plate with significant developments like Girassol, Bonga, Kizomba, Dalia, and others.

The production ramp up from deepwater is behind us; however, the ramp up from ultra-deepwater is still to come. Production from these water depths began in the late 1990s in the US GoM and Brazil, and currently stands at the beginning of a production ramp up that is forecasted to go from the current level of 1.5 MMboe/d in 2014 to more than 5 MMboe/d by 2020.

Ultra-deepwater developments are more complex than deepwater developments in many ways. First and foremost is the water depth. The deeper water brings challenges in many ways and one in particular is with the risers. Not only are pressure and structural integrity issues, but also the weight pulling down on the FPSO becomes significant in ultra-deepwater. By the end of the 2000s flexible production risers were approved down to around 2,000 m (6,560 ft); however, there were rigid and hybrid solutions (riser towers/submerged bouys) capable of handling deeper waters. Currently, there are flexible production risers capable of withstanding 2,500-m (8,200-ft) water depths, and the qualification of equipment for deeper waters is likely to continue. Into the 2020s we might see water depths at around 3,000 m (9,842 ft) with the giant Libra development moving forward in Brazil. These depths are at today's limits, but the hope is that emerging composite flexibles (more strength and less weight) will be qualified to handle water depths beyond 3,000 m.

With the push into ultra-deepwaters, the reservoir pressure and temperature generally increase, adding complexities for both the drilling operation and the processing equipment. Of the deepwater resources expected to go into production over the next five years, approximately 50% have a reservoir pressure above 500 bar (7,252 psi). For the deepwater resources, the equivalent ratio is only 15%. The high initial pressure and large pressure drop over the life of the reservoir brings increased need for injection capacity on the topside. In addition, the ultra-deepwater resources are in general further from shore than the deepwater resources, and due to the share volume of discoveries in presalt Brazil, the ultra-deepwater fields take longer to drill due to the salt layers.

On the positive side, due to the more mature nature of deepwater resources, many of the largest and most prospective fields have already been developed. This favors future ultra-deepwater fields in that the discoveries to be developed on average are larger than the deepwater discoveries. Over the next five years (2015-2019) close to 65% of the ultra-deepwater resources to be brought onstream come from fields larger than 1 Bboe. For the deepwater resources, the same ratio is 30%. In addition, early production tests for several of the Brazilian ultra-deepwater developments show significantly higher flow rates than Petrobras expected.

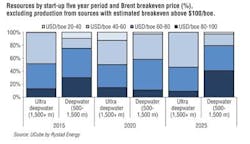

The oil and gas ratio also differs between ultra-deepwater and deepwater resources. Close to 70% of ultra-deepwater resources estimated onstream next five years are oil. For deepwater the oil ratio is only slightly above 40%, reducing the profitability of these compared to the ultra-deepwater developments.

Considering the different aspects of deepwater and ultra-deepwater, one can compare and contrast the robustness of the different resources. There are higher shares of ultra-deepwater resources with break evens below $60/bbl in all three five-year periods, indicating a higher robustness to oil price changes going forward. While approximately 75% of the resources to be put into production 2015-2019 are already sanctioned, most of the resources from 2020 onwards are not. This indicates that the short term effect of a weaker oil price is limited, while a prolonged period with lower oil prices might affect a substantial part of the projects going into the 2020s.

That ultra-deepwater is more robust than deepwater may be contrary to what many believe, but what we see here is that larger fields and higher oil/gas ratios of the ultra-deepwater fields out-weigh many of the increased costs that come with more water depth, higher reservoir pressure, longer drilling times, etc. Another important factor is that the some of the increased costs related to ultra-deepwater developments are coming down. For example, in 2006 the fastest Petrobras was able to drill a presalt well was 134 days. With increased experience, the company set a new record of 60 days in 2013. Not all presalt wells are ultra-deepwater, but the ratio is much higher than for deepwater.

Upcoming ultra-deepwater developments are more robust to changes in oil price than deepwater developments, primarily because of their size. This relates to the ultra-deepwater development boom lagging 15 years behind deepwater developments. Many of these ultra-deepwater developments are in Brazil, which might actually strengthen the robustness further, given that the decision to develop is not only driven by business rationale, but also by political decisions. Of course with everything equal, a deepwater development will be more profitable than an ultra-deepwater one. However, we are now in a situation where, due to size, the ultra-deepwater elephants seem to be cutting in line ahead of the deepwater discoveries and other developments with higher breakeven.