Global deepwater developments: real supply additions or just fighting decline?

Jon Fredrik Müller

Rystad Energy

Deepwater developments have long been touted as one of the most important sources of new oil and gas production. However, production levels have been relatively flat over the last four years, and the historic high is still the 7.2 MMboe/d set back in 2010. So what is going on? Where are these deepwater projects being developed? Is the activity going forward enough to produce results beyond that of just battling decline, or is it time to revise the former positive outlook for the deepwater giants?

Deepwater markets

When the worddeepwater is mentioned in an oil and gas setting, three regions immediately come to mind; Brazil, the US Gulf of Mexico, and West Africa (mainly Angola and Nigeria). Historically, these three regions have dominated the deepwater scene and accounted for approximately 82% of the world's deepwater production in 2013 (deepwater > 1,500 ft). Not surprisingly, the largest deepwater producers are also the largest markets going forward.

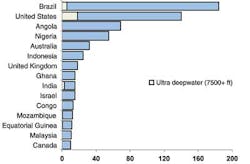

The largest deepwater markets toward 2020 are Brazil, United States, Angola, and Nigeria, accounting for $185, $140, $70 and $55 billion in capex, respectively, over the 2014-2020 period. In fact, the four largest markets are in total 2.5 times larger than the combined contributions from the remaining 11 countries on the list. The majority of the capex is forecasted to be in the deepwater segment from 1,500-7,500 ft. Of the top 15 countries, it is only Brazil, US, and India that have any sizable spend in the ultra-deepwater segment over the forecast period.

Brazil leading the pack

Brazil has been one of the markets that the world's oil and gas industry have rushed toward over the last decade for its massive presalt discoveries. The country now has discovered offshore resources of close to 53 Bboe, only surpassed by Qatar, Iran, and Saudi Arabia with 106, 80, and 64 Bboe of offshore resources, respectively. However, while the Qatar and Iranian resources are close to 70% gas, the Brazilian resources are more than 80% oil (as with Saudi Arabia). With approximately 75% of these resources located in deepwater, it should come as no surprise that Brazil is the biggest deepwater market globally.

The biggest ongoing Brazilian deepwater developments are in the Santos basin. The second, third, and fourth phases of the Lula development will require a total of five large FPSOs. In addition, there will be a need for two FPSOs for the adjacent Iracema structure. Together these phases are estimated to account for $28 billion in capex over the 2014-2020 period. The developments of the giant Buzios field (x-Franco), Sapinhoa North (x-Guara) and Lapa Southwest (x-Carioca) are also under way in the Santos basin. While Buzios will require five FPSOs in a three-phased development, Sapinhoa North will "only" be one FPSO. Lapa will be developed with one leased unit initially, but several units will be needed in subsequent phases. Of fields yet to be sanctioned, Iara, Iara NW, Iara Surround and additional phases of Lula and Lapa (all Petrobras) and Atlanta (Queiroz Galvao E&P) are among the most interesting projects in the Santos basin toward 2020.

It is not only in the Santos basin where field development is going on. Between 2014 and 2020, the Campos basin has several upcoming projects with Petrobras' Tartaruga Verde et Mestica and Parque das Baleias South as the two most interesting, both developed with one FPSO each. In the Espirito Santo basin it is the Parque dos Doces development that is likely to spark most contractor interest. The field is a joint development of three discoveries where Petrobras plans to use a leased FPSO; the tender is reported to come into the market in late 2014/2015.

Although the main presalt discoveries are in the Santos basin, there are other presalt areas along the Brazilian coastline. Both the Espirito Santo basin and the Campos basin have presalt areas. In terms of exploration activity, the Campos basin presalt reservoirs have also received increasing interest recently since the salt layer in the Campos basin is believed to be significantly slimmer than in the Santos basin, and exploitation of these reservoirs is therefore thought to be more straightforward.

Although blessed with tremendous offshore and deepwater resources, the development of the offshore fields and Brazil's oil and gas industry has seen its share of issues. The strict local content requirements have led to a significant cost increase in Brazil and the local supply chain is constrained. This has led several oil field service companies to take large losses on contracts with Petrobras, and project delays seem to be the rule rather than the exception. The cost increase is also affecting the oil companies as the large Brazilian discoveries now are becoming increasingly costly to develop. Although strict local content requirements are in place, several projects have been allowed to move parts of the construction outside of Brazil to reduce delays.

The much touted auction for the Libra field in October 2013 received limited industry interest, mainly due to the operators viewing the requirements for the license as too strict. The oil field, which was originally drilled by Petrobras on contract from ANP on unlicensed acreage, only received 11 bids as opposed to the government's expectations of 40 bids. An increasing realization among Brazilian politicians that strict oil policies might have become a constraint in the development of the country's rich resources sets the scene for the upcoming elections in October 2014. Moderation of some policies might be an outcome even if current president Dilma Rousseff is re-elected.

US deepwater developments

Currently, all deepwater activity in the US is located in the Gulf of Mexico. Development of these resources took a hit with the Macondo blowout in 2010, and drilling deeper than 500 m (1,640 ft) was temporarily banned. However, by 2012 drilling activity was back at regular levels, normalizing that part of the market. In contrast to Brazil, where the capital investments in deepwater resources are dominated by Petrobras (90% 2014-2020), the US market has a broad operator landscape working toward first oil for these discoveries.

Based on their deepwater development agendas, the operators with the forecasted largest spend over the period 2014-2020 are Shell, followed by Chevron and Anadarko. Shell, with a total estimated spend of $19 billion, is currently undertaking the Cardamom Deep, South Deimos, and Stones developments. Going forward, the operator is expected to put the wheels in motion on a semi on Appomattox, with Vicksburg A and B as tiebacks. The operator is also understood to be reviewing the possible use of a TLP or a spar on the Vito discovery.

Chevron is wrapping up theJack/St. Malo development with planned startup later this year. In 2015 production is also planned to start up on the ongoing Big Foot development. Toward 2020, there are possibilities for a second phase on Jack/St. Malo and Tahiti, in addition to the possible development of Buckskin and Moccasin, bringing total forecasted expenditure to $14 billion. Anadarko has both the Lucius and the Heidelberg spar under development, with estimated startup in 2014 and 2017 respectively. In addition, the development of the emerging Shenandoah mini basin is expected to be put into motion by 2020. In total, Anadarko's capex for its deepwater projects in the GoM is forecasted to be $10 billion from 2014 to 2020.

In addition to all the field developments under construction, BP has an interesting initiative running called the 20K project. Currently 15,000 psi sets the limit for what pressure the offshore drilling rigs can safely handle. The 20K project goal is to develop drilling and subsea production equipment that can handle reservoirs with pressures up to 20,000 psi. So far several industry participants have been included in the project, and/or awarded contracts, including Maersk Drilling, KBR, and FMC Technologies. BP is pushing for this technology development, among others, to unlock the potential in the high-pressure discoveries Kaskida and Tiber in the GoM. BP states the goal is to have the solutions ready within the next decade; and, that by pushing the operational envelope, new opportunities will emerge also in the other deepwater markets.

West Africa markets

West Africa as a deepwater region is primarily driven by Angola and Nigeria. Significant development activity is expected in the deepwaters of Angola in the years to come led by the ongoing development of Total's Kaombo project, Eni's Western and Eastern hub, and ExxonMobil's Kizomba Satellites Phase 2. One of the most exciting to-be sanctioned fields is Cobalt Energy's Cameia project, where the plan for development and operation was submitted in May 2014. Other interesting projects include Maersk's Chissonga, Chevron's Lucapa, and BP's West PCC project, where the operator is reported to be leaning toward a small leased FPSO.

In Nigeria, the potential new Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) will continue to delay deepwater investments in the country until it is passed, if it is passed at all. It is viewed as unlikely to be passed before the Presidential and National Assembly elections scheduled for the Feb. 14, 2015. Although there are significant uncertainties regarding the PIB, project sanctioning has not stopped completely. Total sanctioned the giant Egina development in the summer of 2013, and one of the next projects that may come to the market next year is Shell's Bonga Southwest. However, until the PIB is passed, or shelved, the market developments in Nigeria will continue to move at a modest phase.

There is also some activity in the other West African countries, although relatively small compared to Angola and Nigeria. In Ghana, Tullow's sanctioned TEN development, Eni's possible Sankofa project, and Kosmos' to be sanctioned MTAB project will make up a larger share of the market, while in Congo it is the Moho Marine Nord that is the major development.

Rest of world

Brazil, the US GoM, and West Africa are in a league of their own when it comes to deepwater developments this decade. However, there are interesting developments going on in other corners of the world as well.

The fifth largest market by capex investments isAustralia. Here most of the investments are related to additional phases of producing or under development North West Shelf projects like Gorgon and Pluto. There are also some possible stand-alone developments like Scarborough and Greater Laverda. However, developments are likely to move slower going forward given that several of the larger operators have said that they may postpone sanctioning on some projects, due to the lack of capacity and cost inflation in the industry.

Indonesia is potentially the most interesting deepwater market in Asia toward 2020. Projects like Chevron's Indonesia Deepwater Development Project (consisting of, among other, the Gendalo and Gehem discoveries) and INPEX's Abadi FLNG development may give the market a real boost. However, regulatory obstacles pose difficulties in the Indonesian market and progress moves slowly. The industry hopes that the newly elected president Joko "Jokowi" Widodo will deliver on his promises and boost the oil and gas sector by providing enhanced fiscal terms for mature fields and exploration, and removing red-tape.

Several of the other countries have potential projects but there are two countries/regions that merit special attention. Firstly, by the end of this decade there might be burgeoning expenditure in East Africa toward developing deepwater gas discoveries off the coast of Mozambique and Tanzania. Secondly, the Bay du Nord discovery in Canada has contributed to establish Flemish Pass as a new oil play which might result in more discoveries in the years to come, both in Canada and in the similar geology on the northeastern African coast of Morocco and Western Sahara.

Future production trends

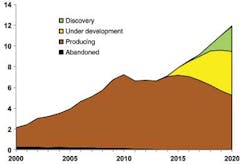

Obviously there are a lot of developments going on around the globe. Most of the large deepwater markets face challenges in some form whether it is local content requirements, constrained supplier chains, bureaucracy and red tape, or uncertain political and regulatory environments. However, challenges aside, when all the projects are summarized, the production outlook is very promising. The "global deepwater oil and gas production by life cycle" figure shows the production profile for all deepwater developments (deeper than 1,500 ft) by the fields' life cycle. By 2015, the production level is forecasted to surpass the old high of 7.2 MMboe/d and reach 7.9 MMboe/d. Even if no new deepwater fields are sanctioned (disregarding the green area), the production is still forecasted to increase toward 2019 and reach a level of 9.6 MMboe/d. By including likely sanctioned discoveries over the period, the production potential reaches 11.9 MMboe/d in 2020.

Overall, deepwater production has the potential to grow production by close to 80% by 2020, compared to the 2013 level. This is truly an achievement, and it is an increase few other sources of supply can expect to match. The development of deepwater resources will continue into the 2020s and as production and drilling technologies continue to improve, the recovery factors will increase, even as the waters become deeper and the distances from shore longer.

The author

Jon Fredrik Müller is a Senior Project Manager within the consulting department of Rystad Energy. His main area of expertise lies in the oil field service segments and particularly within offshore related services. He holds an MSc in Industrial Economics from NTNU, Norway, with specialization in mechanical engineering and finance, including a graduate exchange program at University of Calgary. He works in Rystad Energy's Oslo office.