Island nations off East Africa hold frontier exploration potential

The Comoros, Seychelles, Mauritius attract international interest

Dr. Luke Havemann

ENSafrica

In light of the recent discoveries that have been made offshore East Africa, the archipelagos of the Indian Ocean have received more attention from the international oil and gas industry. While the industry's interest is still somewhat nascent, there is a long road ahead before the hydrocarbon potential thereof can be wholly assessed. Aside from the geographical proximity to the famous plays of East Africa, the marine territory of each of the relevant archipelagos is truly substantial, a factor that adds to their allure, particularly since access-related issues that are renowned for complicating land-based exploration will not apply. There are many islands within the Indian Ocean but the three that are perhaps the most advanced in terms of the degree to which the governments have begun to focus on capturing the interest of international oil companies (IOCs) are the Comoros, Seychelles, and Mauritius. The following is a synopsis of the oil and gas activity in the waters of each of these island nations.

The Comoros

The Comoros gained independence from France in 1975. Since then the tiny nation of roughly 735,000 people has endured 20 coups and only as recently as 2006 did it experience its first peaceful transfer of political power. The Ibrahim Index for African Governance (IIAG), which provides an annual assessment of governance across the continent, ranked the Comoros 32nd out of Africa's 48 sub-Saharan countries. Additionally, Freedom House, a non-governmental organization involved in the advocacy of democracy and human rights, reported in its Freedom in the World 2014 survey that the Comoros is only "partly free" due to, amongst other things, weak rule of law and restrictions on political rights and civil liberties. In spite of these worrying trends, there has been an increase in the number of IOCs that have shown an interest in acquiring acreage within the Comoros and a concomitant rise in the introduction of industry-specific legislation.

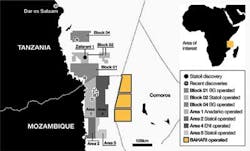

In 2013, the Comorian government implemented a new petroleum code that is on a par with international standards and, soon thereafter, signed an exploration and production-sharing contract (PSC) with Kenyan-based Bahari Resources Ltd. and Discover Exploration Comoros BVC, a unit of London-based Discover Exploration Ltd. The license area, which includes blocks 35, 36, and 37, is on the western boundary of the Comoros and adjacent to Mozambique's Area 1 and Area 4 in the Rovuma Delta where Eni SpA and Anadarko Petroleum Corp. made their gas finds. Proximity to such gas-rich acreage is not the only interesting aspect of the PSC. The terms of the PSC include conducting a regional study of the entire Comorian territory, the results of which will be used to assist with the demarcation of additional blocks and the attraction of additional upstream-related investment.

Bahari and Discover are not the only IOCs that have taken an interest in Comorian acreage. Mauritius-based Safari Petroleum, in partnership with US-based Western Energy Production, has been authorized to explore three of the 40 demarcated blocks. Consequently, although the economist and author, Duncan Clarke, wrote in his book,Crude Continent: The Struggle for Africa's Oil Prize, that the "Comoros…is a lost archipelago in the oil game," it seems that the times are changing and Comoros may have found its way out of the wilderness, so to speak.

Seychelles

The Seychelles consists of 155 islands and possesses the smallest population of any African nation, with roughly 90,000 Seychellois living in the archipelago. The island nation is ranked fifth on the IIAG. With relatively good governance and a small population, the discovery of commercial quantities of hydrocarbons could have a dramatic impact on the lives of the Seychellois. However, it is underexplored and only four exploratory wells have been drilled. The most recent was drilled by Enterprise Oil in 1995, and it was dry. The other three wells were drilled in the early 1980s by Amoco and, although commercial quantities of hydrocarbons were not discovered, there were oil and gas shows, thereby proving that Seychelles possesses a working hydrocarbon system.

Two IOCs hold exploration licenses in the waters of the Seychelles, namely, Afren, a UK-listed company, and WHL Energy, an Australian-listed company. In August 2014, two new applications for exploration blocks were made by means of the Seychelles so-called Open File Licensing Initiative. The Open File award process works as follows: An application for a 10,000-sq km (3,861-sq mi) area can be made at any time, then verification that certain minimum criteria have been met will take place under the auspices of PetroSeychelles, the national oil company of Seychelles. Then there will be a notice of the application's filing and the solicitation of competitive applications (with a 90-day limit). As far as the two new applications are concerned, the 90-day period within which interested companies may submit competing bids for the same areas, commenced on Aug. 18, 2014, and is drawing to a close. Consequently, it may not be long before the number of entities holding exploration licenses in Seychellois waters doubles.

Even though the industry maintains a minor presence in the Seychelles, the country is, from a regulatory perspective, fairly well-placed to accommodate many more IOCs should a discovery trigger a wave of interest. Not only does the country possess industry-specific legislation and an efficient licensing process, but also it has a readily downloadable model petroleum agreement that was developed with Norwegian assistance during 2013. The government has recognized the importance the discovery of petroleum would have and it has put in place a legal framework that facilitates exploration within its marine territory.

Mauritius

Mauritius, which has a population of roughly 1.3 million, obtained its independence from the UK in 1968. Since then it has moved from a predominantly low-income, agrarian-focused economy to a diversified, upper middle-income affair where the economy rests on, amongst other things, tourism, manufacturing, fishing, and financial services. Mauritius ranks first on the IIAG and in 2013, for the fifth consecutive year, was the highest ranking African country in the World Bank's "Ease of Doing Business" report, which is based on a variety of factors including economic openness, regulatory efficiency, and the rule of law. However, the country does not have any proven oil or gas reserves. All of the fossil fuels that are required to maintain the Mauritian economy are imported and Mauritians consume more than 25,000 b/d of petroleum products.

While the presence of commercial quantities of hydrocarbons could dramatically reduce the country's dependency on foreign resources and strengthen its economy, little exploration has occurred. Following an exploration program conducted by Texaco in the 1970s, the results of which were inconclusive, it appears that only India's Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC) has shown an interest in conducting limited exploration within Mauritian waters. As such, the hydrocarbon potential of Mauritius remains an unanswered question and, considering the country has one of the largest exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in the world, it is a question that may take a while to answer.

However, Seychelles and Mauritius jointly have taken steps that may help to shed light on the hydrocarbon potential of the latter. In 2011, following a jointly submitted claim to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf for 396,000 sq km (152,896 sq mi) of the continental shelf beyond the 200-nautical mile EEZs of the two countries, Mauritius and Seychelles were granted joint rights to manage the relevant area, namely, the so-called joint management area (JMA). The two countries are establishing a Joint Commission to manage, among other things, the exploitation of resources of the seabed within the JMA. Also in August 2013, it was announced that an authority would be established to manage oil and gas activities in the JMA. Although the relevant announcements went so far as to state that all revenues would be shared on a 50/50 basis, the two countries are still working on the requisite legal and administrative frameworks. No indication has been given as to when the JMA will be opened for oil and gas-related exploration. Nevertheless, the establishment of the JMA and the creation of frameworks that will allow for the exploration for oil and gas are commendable steps that may well shed some light on the hydrocarbon potential of Mauritius.

A potential hurdle that the country will need to overcome if it wishes to host a prosperous oil and gas industry, is the fact that the law that currently governs upstream activities in Mauritius, the Petroleum Act 6 of 1970, is out of date and out of step with best international practice. The act is three pages and contains 11 sections; it cannot be expected to govern a modern oil and gas industry. The act ought to be revised to attract more IOCs by offering terms that encourage exploration. In view of the establishment of the JMA and the fairly recent upswing in oil and gas activities in Seychelles, the revising of the act should take comparative cognizance of the approach adopted by Seychelles and, of course, international best practice vis-à-vis oil and gas-related legislative frameworks.

Although Mauritius is, from the perspective of general good governance, some distance ahead of Seychelles and the Comoros, it is not the leader of the pack, so to speak, when it comes to industry-specific developments. The oil and gas industry in Mauritian waters is truly embryonic and, without a significant rise in exploration-related activities, proven reserves appear to be a distant prospect.

Conclusion

Although these IOCs have an admirable appetite for exploration in what are still considered to be frontier waters, Comorian, Seychellois, and Mauritian dreams of hydrocarbon-based wealth must remain tempered by the possibility that the impending exploration may reveal a lack of commercially viable reserves. As Duncan Clarke wrote in his previously mentioned book, "New seismic effort could in time put Comoros on the oil map – or take it off it." It will only be as a result of heightened exploration that the question of whether or not archipelagos of the Indian Ocean possess significant oil and gas reserves will be answered.

Oil and gas activity off the islands of the Indian Ocean is unambiguously embryonic. Nevertheless, it is clear that these islands are becoming increasingly attractive and they may well demonstrate that not all the action, so to speak, is to be found on the continent itself. According to Eddie Belle, CEO of PetroSeychelles: "Once we have the first discovery, then there will be a flood of companies."