Offshore industry focuses on crane safety

Jennifer Pallanich Hull

Gulf of Mexico Editor

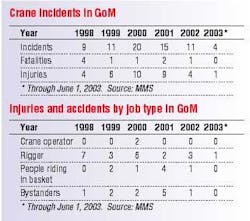

An integral part of day-to-day work offshore, crane operations are a risky business, a fact that industry groups are striving to change. As of mid-year, the US Minerals Management Service showed four crane safety incidents with one injury.

"Cranes came to the forefront in late '90s when we started to recognize some trends," said Joe Gordon, chief of the MMS's office of safety management.

Fatalities and serious injuries awakened both the industry and the MMS to dangers associated with crane operations. The agency began organizing workshops to focus on crane operations and emerging trends. The American Petroleum Institute, which has specifications relating to crane safety, has a 2C specification, recently revised, that ensures a purchased crane is safe, and a 2D specification that ensures it remains safe. Gordon said the realization that riggers were most often injured or killed led to the addition of rigger training to API specification 2D.

"What we've seen the past 18 months, two years, the incidents have gone down, but we're still seeing a problem," he said.

Most incidents are a near miss, he said, but the difference between a near miss and a fatality is often a foot to the left or right. The problems "in the Gulf of Mexico are problems they're seeing in other areas of the world," Gordon said.

The two most obvious trends are rigger training and rental cranes, he said, and other problems include operator error, overloaded cranes, and lifting in poor weather conditions. The MMS has posted several actions to prevent crane accidents:

- Follow an effective preventive maintenance and inspection program

- Value communication, planning, and supervisory controls when moving or disassembling cranes

- Properly rig loads

- Properly train operators and riggers

- Ensure cranes are adequate to lift loads.

Overloading cranes is an obstacle to safe crane operation, and Energy Cranes has worked hard to keep its employees alert to crane load capacities, said Dale Angelo, director of safety, health, and environment for Energy Cranes.

"Those habits are changing. People are becoming more aware of the serious consequences," he said.

At another company, Superior Energy's 44 marine vessels use a variety of cranes, ranging from a 65-ft-leg liftboat with a small utility crane to a 250-ft crane with dual-leg-mounted cranes. In Superior Energy's efforts to make crane operations incident free, the company has taken a three-tiered approach involving inspections, maintenance, and employee behavior.

"A few years ago, the management identified that they were ready to do something about eliminating these problems from their business," said Bill Folse, the health, safety, and environment (HSE) manager for the marine division at Superior Energy Services.

The company set up a maintenance department for the cranes and instituted training sessions, he said. Additionally, Superior Energy gave its employees the authority to halt work that could be hazardous or an abuse of equipment, or work that looks as if it might lead to mechanical failure or injury.

"There's a no-prisoners approach here," Folse said. "We go in and take care of the problem, and that way we know it's done right."

null

While there are root causes in most incidents, he said, behavioral causes often could have prevented the incident. "We're trying to develop the human element as the ultimate barrier to stop those cycles," Folse said.

Operating a seemingly sound crane with a disabled safety system can cause thousands of dollars in damage to the crane, Folse said, so Superior Energy requires preventive inspections. He said the complete program has halved maintenance and repair costs.

For people to prevent accidents, they must be properly trained. Louisiana-based Moxie Media Inc. has designed materials for crane rigger and operator training.

"A number of schools and companies use our programs as the basis of their training," said Martin Glenday, president of Moxie Media Inc.

The modules, geared to the different types of cranes in use in the offshore sector, include changes from the latest API 2D in that anyone who is involved with handling the crane or load must be rigger trained, Glenday said. The training sets, available in multiple languages, are popular for two reasons.

"First, there's a regulatory need for it. Second, crane accidents are probably the most deadly incident out there," he said.

Energy Cranes, formed by Sparrows Offshore, American Aero Cranes, and Titan Industries, retrains its mechanics and riggers every two years, more frequently than every four years called for by the API. The company hopes for an authentication of training programs, such as the training system certification program the API is working to create, Angelo said.

API specifications have also addressed inspection and maintenance. The MMS inspects pedestal-mounted cranes on fixed platforms, and the US Coast Guard inspects cranes on floating installations like TLPs, spars, and MODUs. The USCG allows classification societies like the American Bureau of Shipping and qualified third parties to inspect cranes annually. The USCG plans to update its regulations for crane inspections and safety soon, said Lieutenant Commander John Cushing, USCG chief of the compliance branch for the 8th Coast Guard District.

"There have been some pretty tragic accidents involving cranes," Cushing said. "We're pleased that there are so many organizations taking a look at crane safety."

ABS's Guide for Certification of Cranes outlines the requirements for cranes on vessels that are classed with the ABS.

"Maintenance is the key to keeping it operating safely," said Dave Forsyth, manager for offshore technology and business development for ABS Americas.

Every five years, cranes undergo a proof load test to show the crane can operate within designated limits, he said. The review focuses on the crane's location on the vessel and supporting structures to ensure it can withstand forces on it.

"Each design requires a specific examination," Forsyth said. "Loads will be presented to the structure in different ways."

But inspections by regulatory agencies aren't sufficient. Crane operators themselves conduct pre-use inspections, in which they look at the crane and the task ahead before beginning the activity, somewhat like a pilot's pre-flight check.

Safely engineered

A safety guidelines committee studied existing API 2C specifications for cranes and put forward some significant changes in the sixth revision, said API 2C Task Group Chairman Randy Long. The API committee formed about a year ago to work up the new version, expected to be published in early 2004.

"The biggest change was to provide more guidance on the design of cranes for floating platforms," he said.

Long said the guidelines needed to address motions associated with floating platforms and supply boats plus the movements of the cranes themselves. The new guidelines incorporate platform motion by studying the motion characteristics of the floating platform on which the crane is mounted and designing the crane to work with those motions, Long said.

The specifications make allowances for unknowns. In the early stage of design, the motion characteristics of the platform may not be known. Generic guidelines will allow engineers to use generic motion models until the actual characteristics of the platform are known, Long said.

Houston-based crane manufacturer Seatrax, which was involved in the API 2C rewrite, said its cranes come equipped with safety features beyond those required by API 2C.

"We try to design and build the safest product with regard to the robust design of the structure, the robust design of the hoisting equipment, and a machine that is simple enough to the operator that the operator can operate the crane safely," said Seatrax Vice President of Sales and Marketing John Hale.

One safety feature Seatrax incorporates into its cranes, which range from 20 tons to 1,200 tons, is the patented Anti-Two-Block system that prevents contact between the hook block or ball and the boom point, which has historically been a factor in crane accidents. The system solves the problem through geometry by locating the hoists in the base section of the boom rather than on the revolving structure. The hook block cannot be drawn into the boom point as the boom lowers because the hoist and boom both move concurrently.

"You cannot two-block our cranes," Hale said.

Energy Cranes manufactures API-monogrammed cranes ranging from 3 to 175 tons. The company also services and manages cranes worldwide, which can be a big business in an area where much of the fleet was built long ago.

The aging crane fleet, with many units built before 1983, is one of the bigger safety issues in the Gulf, Angelo said.

"There's a lot of old steel in the Gulf. They're worn out. They've had a lot of stress put on them, which is a concern for safety," he said.

Most cranes are engineered to last 25 years with proper maintenance, he said, and many of the older cranes are now being replaced. Additionally, he said, the industry is working to replace and phase out the older friction-type cranes, which were land-based cranes taken off tracks and mounted to a platform although not designed to be mounted on a platform.

Some safety features can be added to the cranes post-manufacture. Crane monitors give the operator in the cab better visibility of the hook-up process.

"What drove some of those boom cameras was with big platforms and big cranes, that was a very convenient and very viable way for them to monitor the operations," Gordon said.

Oceanor's crane boom camera systems can record or display live, high-resolution footage so the operator can watch the hook-up process, said Rob Smith, sales and marketing manager and oceanographer at Fugro GEOS. Fugro purchased Oceanor earlier this year. The most straightforward systems feature the camera on the boom crane with a screen in the cab. An additional camera can be placed on the winch.

"It reduces risk during a blind lift," he said.

Smith said companies, in their commitment to safety, have begun adding crane monitors in offshore applications even in places without requirements dictating their use. Drilling contractor Transocean recommended Oceanor's deck crane boom cameras as standard equipment on their fleet in late 2000.

Renting lifting ability

Rental cranes, on site for a short time to perform a specific task, can pose increased risks and become a focus in the crane safety spotlight. Sometimes the platform layout will not allow rig-up as planned, so the crew might adjust the configuration, the MMS's Gordon said. "Those are the types of situations that get them into trouble."

In most rental cases, he said, the rental crane crew rigs the crane up and down, but company personnel and rental crew use the crane.

"What we've asked the operators to do is make sure there's a (job safety analysis) JSA done on the rig-up operation, and make sure that the prognosis with rigging out the crane is appropriate for the site where it's going to be rigged up," Gordon said. The JSA looks at hazards, walks through the operation's steps, anticipates problems, and notes contingency plans.

Energy Cranes works to ensure safe rental crane operation by having the company's trained employees operate the rented cranes, Angelo said. "We like to operate our own equipment," he said.