New twist on an old phrase

Back in the day, the ultimate over-simplification of the force motivating oil producers was the phrase, "Drilling for Dollars." It was a neat way to display the inbred optimism of the wildcatter's spirit. Back then, with dry hole ratios hovering around 90%, the industry needed all the optimism it could muster. Luck played a major role in deciding whether a wildcatter would strike it rich or drill a duster.

In the early part of the 20th century, slick-tongued promoters scoured the country looking for investors so they could keep drilling. Many were delighted with a dry hole because that meant they did not have to pay off the people who held fractions of the lease totaling 200% or 300%. In many cases, the science used in determining where to drill was loosely termed "closeology" – drill as close as possible to a producer and you were likely to bring in a well.

Since subsurface geology was more art than science, drillers employed "scouts" who frequented the saloons around the oil patch trying to find out who was drilling and how deep they were. Scouts were even seen to sneak up to a competitor's rig that was making a trip to try to count the number of stands in the derrick so they could estimate the well's depth.

The industry has come a long, long way since those days of wooden rigs and iron men. Science and technology has enabled us to continue drilling, and even to reduce the dry hole ratios to 60% or less. At the forefront of this applied science is the ubiquitous drill bit.

In this issue ofOffshore, there is a story about bit innovations that, in their effect, truly pay off the phrase "Drilling for Dollars." However, since the bit has nothing to do with whether the well penetrates productive strata, the dollars we are writing about do not come from production, they come from cost reduction.

Traditionally, the highest cost item on an AFE is rig cost. The Independent Petroleum Association of America (IPAA) used to do an annual survey of the cost of drilling and equipping an oil well. Rig costs always led, averaging 35% of the total. Naturally, people reasoned, "If we can reduce drilling time, we can reduce our biggest cost item." And the race was on.

The conventional wisdom gravitated toward increasing rate of penetration (ROP) to save time, and many of the innovations developed by bit providers were aimed at designs that could boost ROP. If you look through oil magazine archives, you will find that almost all bit advertisements focus on ROP. It is logical. Wells were vertical, for the most part. Most geocolumns were conventional and fairly easy to drill. Few wells were deeper than 15,000 ft (4,572 m), and bits just had to make it to the next casing point, so ROP was the only parameter that played a major role in cost reduction. Offshore was no exception.

As oil and gas became harder to find, drilling became tougher. Well depths increased both offshore and on land. Offshore drillers moved to increasingly deeper waters, where individual wells could not be produced economically from single jacket platforms. It became more economical to drill multiple wells from a single platform, and this called for directional wells to reach the far limits of the reservoirs. Finally, water depth exceeded the economic limit of fixed platforms and floating production facilities were needed. On land, there was a similar revolution, as plays like the Austin Chalk required long lateral wells.

The upshot of these changes altered bit economics. In many cases, it was not possible to drill to the next casing point with a single bit. Intermediate formations became tougher to drill, with hard streaks and highly abrasive sections. Bits became worn before they could complete drilling a section. Suddenly ROP stopped being the key parameter in rig cost reduction. It became more important to extend bit life so it could drill a section in one trip, rather than to drill fast.

Deepwater offshore rig rates were steadily climbing, and tripping pipe could consume 12 to 24 hours. If one pipe trip could be eliminated by extending bit life, it would save far more rig hours than increasing penetration rate.

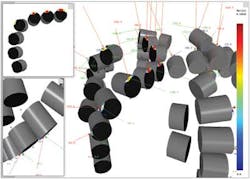

As you read the story on bit technology advances, see how many of the latest innovations are directed at extending bit life. ROP is still important, but increasing ROP has fallen behind as the number one design goal. For the past couple of years, the bit manufacturers' advertisements now talk about their products' ability to "Drill the build section and the lateral in a single trip." Most recently, they are starting to say, "Drill the vertical, build, and lateral sections in one trip!"

Offshore, dual-gradient technology has been introduced to allow safe margin drilling so many casing points can be eliminated. This will save considerable money in casing and cementing costs as well as logging costs. However, to take advantage of this benefit, the drill bits must be able to drill the resulting longer sections without wearing out. Again, the aim is reduction of pipe trips, not increasing ROP. When dual-gradient drilling takes off, the bit providers will be ready.

Rigs are truly drilling for dollars these days. Oh sure, they are using every skill they have to steer wells through reservoir "sweet spots" and land long laterals in prolific pay zones to maximize reservoir contact and productivity. But they are also drilling to save dollars by maximizing bit life to minimize the number of necessary bit trips. And if their subsequent designs have to give up a bit of ROP to achieve longer bit life, they are willing to make that sacrifice.

Editor's note: Dick Ghiselin's article, "Bit technology continues to advance," can be found on page 86.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com