Industry experts weigh in on risk management

Industry experts weigh in on risk management

Value of collaborative solutions emphasized

A Staff Report

Unavoidably, process safety risks are often managed in different parts of an organization. Bringing them all together in a consolidated way, to view their impact on the operational reality of hydrocarbon asset or plant is a real challenge.

What the industry needs is to make sure everyone assesses risk using the same criteria – and has a practical understanding of how their decisions directly or indirectly influence the risk picture, and ultimately, process safety performance. By making process safety more “operational,” that is ensuring front line personnel are aware of their roles and responsibilities, and are effectively and consistently implementing processes and procedures, we can reduce incidents and improve sustainable production.

So what is today’s reality of risk in the hydrocarbon sector? Recently, Petrotechnics hosted a roundtable discussion in which senior industry executives discussed what happens when process safety intent meets the reality of operations. This includes how the industry thinks it manages risk; how it actually manages it; and how it can improve it practically and tangibly.

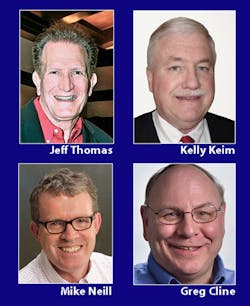

Participants included Mike Neill, President, Petrotechnics USA, Former BP Upstream (MN); Jeff Thomas, Upstream Offshore Sr. Process Safety and Reliability Consultant (JT); Kelly Keim, Chief Process Safety Engineer (retired) (KK); and Greg Cline, Principal Market Analyst, Aberdeen Group (GC).

Question: Industry regulation is at an all-time high. Every operator is committed to safety and risk avoidance. So why do you think incidents and accidents still happen?

JT:There are a number of reasons why accidents still happen. First, not all countries have process safety regulations. Second, even where good, detailed regulations exist, it’s hard to implement all the processes and procedures they require 100% correctly, all the time. There are often conflicting priorities, particularly in the field, between safety, production, and cost. In addition, there are often not thorough operating and maintenance procedures that cover all modes of operations, such as start-up, shutdown and other infrequent tasks. In some cases, companies in countries without regulations have implemented excellent PSM programs - so adding regulations may not always be the answer.

GC:Incidents and accidents depend on many things, including the regulatory environment and the overall level of safety awareness. And often it’s just human nature. People try to prepare and create a culture of safety, but slip-ups happen.

JT: Also, people don’t always understand all the hazards or safeguards. They get used to doing things a certain way, and if nothing has happened, they feel it’s okay to continue, even if it’s not the safest thing to do. In addition, we do not often identify all the hazards, especially those related to infrequent modes of operation, like start-up and shutdown, where a majority of incidents occur. Human factors are not generally evaluated and included in most process safety management systems, so we often “set the operators up to make errors.”

KK:But it’s important to note, accident rates for process safety incidents across the refining and petrochemical industries are actually incredibly low.

MN:I’d say most people in the industry think, ‘I could almost guarantee we will have an accident,’ rather than, ‘I can guarantee that we won’t.’ But they don’t know when, and they don’t know how big. And the chances are if you’re a big organization with a lot of operations, you pretty much know eventually something will happen.

When it comes to offshore facilities, there has never been a more critical need in the industry to address risk management. The design of offshore structures forces a compromise between safety and construction costs. Not controversy, just a fact.

KK:The good news is the American Petroleum Institute (API), American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) and the American Chemistry Council (ACC) collect information on causes and causal factors on a consistent basis. They’re beginning to get a much clearer picture of process safety related issues. Traditionally the industry looked at facility causes – equipment failure, corrosion, etc. And those are still big factors. But the greatest proportion of incidents, based on industry evidence, is related to human performance, which is people failing to execute a procedure properly, or missing an operating step.

MN:Whether this is carried out under the regulation of a safety case regime, such as in the North Sea, or under the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement’s (BSEE) Safety and Environmental Management Systems (SEMS) regulations in the Gulf of Mexico, the results are effectively the same; an extensive array of risk control and barrier systems whose design performance is sufficient to mitigate the residual risk down to a level where it is safe for people to live and work.

There’s a lot of focus on humans as the weak link in the chain. That’s obviously part of it. But as much as we blame individuals when things go wrong, we need to credit them for reacting and recovering from problems. Where poor decisions are seen as the root cause of incidents, we need to examine whether competence was lacking or if people just did not have the correct information from which to make a decision.

KK:We’re only just learning how to classify, let alone improve human performance. There’s still a lot to do. And the industry does seek to get better – by making reference to the nuclear and airline industries as shining examples. Those industries addressed things like equipment design, maintenance, management systems and people simultaneously, without preference. For example, in oil and gas, the Mexico City and Bhopal disasters sparked PSM regulations in the US focusing on systems and then eventually people. I think the nuclear and airline industries have been far more successful versus the oil and gas industry’s phased approach.

Question: Is there a gap between what process safety KPIs and operational management systems are telling us and the feeling on the front line?

MN: I think there are. I’ve heard anecdotally from operators the KPIs say one thing and the reality on the plant is another.

JT: A lot of people are still trying to figure out the process safety indicators they should focus on. We’ve only had API standards in place for less than ten years. There’s also probably a communication gap between field and office personnel, engineers, and management who set up process safety indicators and processes. Generally these indicators are not clearly communicated at an operator level in terms of what they are and their importance. I’m not sure actions are taken as a result of the process safety related data and the KPIs produced. One important KPI mentioned in the CCPS book on incident investigation is near miss data. It is critical to report both incidents and near misses, and periodically analyze them to determine causal factors and root causes, in order to prevent future incidents.

KK:I don’t think we do a great job on KPIs. I know very few sites that make a big deal of reporting their process safety performance to operations. They also don’t publicize their safety-critical equipment performance and inspections. And so, if operations aren’t aware, performance starts to slip.

GC:There’s always a gap, and there shouldn’t be. We need to put capabilities in place to minimize gaps and ensure metrics are available enterprise-wide. Also, it’s important that peoples’ perception of certain metrics match the reality of operations.

MN:Major accidents are by definition low frequency but high consequence. So if something happens, you can’t really make a judgement on whether there is a trend, or whether you’re particularly vulnerable. Some people try and extrapolate near misses and look at other performance indicators, but a lot of KPIs are based on how well an organization implements safety processes.

KK:Evaluating risk is always somewhat subjective. And for the most part, companies have not been terribly transparent in the information they use for monitoring process safety risk. Most people can point to their numbers for personnel injuries and behavioral safety observations – but catastrophic events are rare, so they aren’t front of mind, even if the risk is always there.

Question: Does the reality of risk management measure up to the intent of risk management?

JT: I’d say most companies probably recognize their process safety performance is not where they want it. But on the whole, we’re doing a better job today of understanding risk than we did, when I started, say, 30 to 40 years ago.

MN:People are experienced enough to know that hazardous industries mean risky business. I don’t think people would publicly admit that risk is so unpredictable. But other industries, nuclear and airline, have managed to eliminate some sources of unpredictable risk. These sectors put a lot of emphasis on training, stop work authority and redundancies in design so that if a system fails, there’s another that would take over. In the process industries, we’ve become somewhat normalized to risk, and we don’t come anywhere close to investing the same level of risk management resources. But there is a lot to gain from investing in safety. Typically, with safety comes improved operational performance.

KK:Actually, I do think there’s an undue confidence at both the executive and field levels that “those things just don’t happen to us.” There isn’t that everyday sense of caution that should be present in people who are one procedure away from a major catastrophic event. Most plant workers and managers have never experienced a major process safety event, so they believe it won’t happen to them. We know that’s not true.

GC:Real safety happens on the ground when people internalize it and don’t view it as a burden on everyday business. That means risk exposure must be made visible, prominent and available so everyone can understand its impact on the operational reality.

KK:When I first started in the industry 40 years ago, fires and explosions were relatively common. Most workers had experienced one. There was a belief that these could happen, and people paid attention to avoid them. There was maybe a negative that people felt responsible for putting their own lives at risk to minimize those events. Thankfully, we’ve almost eliminated this ‘cowboy approach.’ But now the industry has the newest and rawest process safety data. We’ve really only been managing it for five years or so. With more time and data, we’ll be able to say whether we’re actually better than we think.

Question: Do you think the relationship between PSM and operational risk management is close enough?

GC:No. I think PSM is always aspirational, and the relationship between process safety and its impact on front-line operations can be better understood.

JT: There are gaps in most cases. There’s been a lot of work focused on developing PSM systems, improving risk related practices, and developing PSM tools. But there is often a “disconnect” between what the practices and processes intend and what actually happens at the grassroots operator level. Lots of companies are working on it – but I don’t know any that have a magic bullet.

MN: The relatively new SEMS regulations in the Gulf of Mexico and the more mature Safety Case Regulations seen in Europe and Australasia have an emphasis on process safety, barrier management, and more importantly, communication to all staff of the hazards and protections. In reality, process safety is in a different part of the organization, so operations personnel struggle to understand some of the language and how to apply it to their reality. But then, process safety people sit in a world of scenarios and models in which it is easy to diverge from reality. It’s a bit like your house being about to fall down because it has wood termites, but I’m spending all my time painting it! I focus all my efforts on a process for painting. It’s a false sense of security. Operators need to know how to practically apply process safety on the plant.

KK:Operators don’t get a good picture of how change affects risk management or the aspects of the job where they are the critical factor in managing risk. Often, when investigating the failure of an asset, the question to operations is typically, “Why weren’t you paying better attention?” And the challenge back, “Pay better attention to what, and how?”

MN:Process safety designs safeguards. It doesn’t really look at how risk is managed in real-time. But then, process safety teams are also not a strong voice in the organization. They don’t have a significant budget and are always vying for priority with plenty of other groups in the organization.

KK:Our risk models rely on the operator for 99% execution. We don’t often explain where operations teams really need to be at the top of their game. And we don’t explain that when facilities change, they are potentially operating in a higher risk environment. The CSB report on the explosion of the electrostatic precipitator in the Torrance refinery pointed out that as Operations became focused on the tasks required to complete the shutdown, they became unaware that the situation continued to change. They didn’t know the importance of the key process safety barriers they controlled.

JT: It takes a lot of hard work and communication between the engineer, management, and the operators on what risk management is all about.

Question: Who is responsible for managing risk?

JT: Everyone, from the CEO, all the way to an operator, mechanic, engineer, supervisor – all levels of management and workers. Everyone has a key and different role to play, but risk management should permeate throughout the organization.

KK:We’re a long way from being able to take the operator out of risk management, particularly in refining and petrochemicals. So management is responsible for having systems in place to make operators aware of changing risk patterns. Ultimately, executives have to recognize this is part of managing process safety risk.

MN: Yes, ultimately it lands at the top of the tree. Executives have to make sure the right people are involved in the right processes and they do the right things. But I would say operations are in control of the plan. They are at the sharp end, so they should be satisfied personally that the risk level is acceptable. That said, where there are multiple levels of decision-making, it can be confusing when it comes to who owns risk.

GC: In our most recent Aberdeen Group environmental, health and safety study, about a third of respondents have a formal risk management organization in place. That’s presumably how they establish a framework for risk management. Does it build a risk awareness culture across the organization? It can. Whether those companies have also got the necessary collaborative approach across business units to make it happen is another question.

Question: What critical process safety information do people who make the daily decisions about operating a plant need?

GC: When we talk about making daily decisions, operational data must correlate with the management of process safety and vis-a-vis. Management needs to analyze the plant and the processes that relate to PSM. And then this needs to be incorporated into operational dashboards – in an actionable way.

MN: Operators need data that clearly shows if something unexpected is happening, what the impact could be, how that affects the program of work, the threats it creates – and of course, the effect of any remedial reaction. Their number one priority is containment, so they need data on the integrity of pipes and vessels, and critically, the condition of the actual detection systems themselves.

JT: There is a lot of information that people need to make decisions. KPIs are needed at the management level to help make decisions about operations, resources, and priorities. At the engineering level, they need inspection and test data to help determine frequencies of maintenance and repairs. And then the operator needs data to understand the current state of a process and what the risk is of the tasks they are completing.

One of the key issues is there is so much data; it’s hard to figure out what is really meaningful. So you need to clearly identify that type of information. And then the importance and the timing of activities are key, so operators can determine what’s urgent and what can wait. You need a whole picture of risk based on data – so decisions aren’t isolated from everything else that’s going on in a facility.

KK: That consolidation of information is certainly vital to more rational decision-making. The trouble is we don’t provide consolidated systems for operations to effectively assess if they can take one more step in their procedure.

With the Macondo blowout, for example, roughly 11 layers of protection needed to be in place to prevent the scenario that happened. One-by-one those layers of protection were whittled away. The response was always, “well that’s okay because we’ve got this other ultimate layer of protection.”

So it shows even a plant with multiple protection layers can experience a major hazard because of an accumulation of relatively harmless decisions. The current process safety barrier status must be visible to operations, the front line but also management so appropriate decisions can be made.

MN:Ultimately, operators need data that shows whether it is safe to operate the plant. Many Gulf of Mexico facilities are reaching maturity. Local operators and those in other basins should take note of what is happening in the North Sea and implement changes to the way operational risk and activities are currently managed.

Question: How well informed are front line leaders and workers about the role of process safety barriers in preventing incidents?

KK:I’d say they’re only barely aware of the layers of protection. In many cases, operations – even first-line engineers – are not aware of the scenarios that could lead to a catastrophic event in their unit. The scenarios have never really been collated in a useful way for them. I think there’s a general failure to really communicate, on a shift-by-shift basis, the status of key barriers on any given day. For example, I spoke to a team recently where there was something wrong with a detective device for a piece of safety-critical equipment. The company said “the operator is going to pay more attention,” but nobody translated that into what that meant for the operator and how they would do it. And that’s the most important thing when operations are making daily decisions.

JT:It varies by facility. To be frank, some don’t have a clue. But some are doing a pretty good job. There is an opportunity for improvement to ensure operators, maintenance technicians, and the front line really understand key hazards, safeguards and the ideal state of the process safety barriers. That’s absolutely critical. I haven’t seen a lot of facilities yet where they really have a good handle on that the barriers and how they inter-relate to prevent an incident.

GC: I think building a culture with the right tools, right attitudes, and right training can enhance the awareness of process safety barriers by making them part of the standard operating procedures of front line leaders and workers.

MN:I think that there is still a lack of information available. And the further down the chain you go, the more abstract some of that information is. I’m not sure people really understand risk and what it means to them. And that can put them in a vulnerable position to be exposed to risk they don’t understand. If they did understand it, I think some of their decisions might be different. I think that’s the industry’s challenge. We need to give the front line the ability to be better informed about the possible consequences of their actions – even when making minor decisions.

Question: What are the current obstacles to access this information in a timely manner and how can they be eliminated?

JT: There are a few. First, we have so much data, particularly with things like digital process control systems (DCS), safety instrumented systems (SIS), maintenance systems, etc. We get information overload, and it’s not always clear what’s most important. Second, there can be a lag in the data. We don’t always get it when we need it – and things can be missed. Third, maintenance management and process control systems don’t always make it easy to extract data. And that’s just the start.

KK: The information is there, but it’s often in lots of different systems – some of which may still be paper-based. Even for a process safety engineer who’s been on the site forever, it will take time to pull all that data together. And if it isn’t consolidated and condensed in useful forms, nobody actually uses it for making critical risk-based decisions.

GC: The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) is enabling a new era where we have the capability to monitor and improve processes to ensure they’re safe. Safety must be implicit. I think, to the extent that operators can connect operations with the information needed, via IIoT or another framework, they can overcome risk and help prevent incidents.

MN: Offshore operators in particular have a wealth of data streams and systems to help manage offshore assets from ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning), EAM (Enterprise Asset Management), maintenance management systems, inspection databases, and planning and scheduling systems. The unfortunate reality is these systems are spread far and wide in silos across the business, making them often inaccessible in a useful manner to the majority. This often results in frontline people needing to make day-to-day activity decisions in the absence of current information. Data is the root of the problem.

We need to connect the data we have. We also need ways of assessing the impact of doing something or – equally important – not doing something. But individuals also need multiple viewpoints – from maintenance and asset integrity to drilling and subsea. That’s the source of informed decision-making, using technology to put everyone in a much better position.

As a passionate offshore VP at a previous Center for Offshore Safety Forum stated, the industry must evolve how it mitigates operational risk. By using collaborative risk management solutions, operators can broaden the planning-to-execution business processes and ensure continuous process learning.

Question: How can operators maintain their safety and risk management standards over time?

KK: Today, for the most part, operators don’t get feedback on their risk levels, let alone their risk management performance. Even companies that are doing a good job of tracking tier-three and four process safety indicators are basing performance on lagging data. And they’re certainly not communicating this to operations. If you don’t get good feedback, you can’t improve. I’m just not aware of anyone using any process safety solution, other than the most basic tools like work permit systems to manage it.

JT:I think there is merit to having a tool that shows an overall picture of hazards, operational risk, barriers and safeguards – updated on a real-time basis. Also, constant communication with operations is key, so they know the impact of any change, for example management of change (MoC), and how best to adjust.

GC: Safety and risk factors change all the time, so best practice must be responsive to changing conditions. Creative solutions can help organizations maintain and actually improve their safety performance over time.

MN:Safety standards define our risk tolerance. And risk tolerance is not an exact science. It’s an interpretation of risk and whether certain outcomes are acceptable. And that’s hard. Of course, managers would love to have a physical device with traffic signals that tell them they need to do something or prioritize differently. We all would. But it’s more about being sure that systems are effective. It’s about an attitude of constant vigilance and questioning – giving people confidence in each other and their data, and empowering them with systems they can rely on. •

The roundtable participants

Jeff Thomas is Sr. Process Safety and Reliability Engineer, Process Improvement Institute.Jeff Thomas has 40+ years of experience in the Upstream oil and gas industry, including positions in process/facilities engineering, production operations, and process safety management (PSM). He has a B.S. in Chemical Engineering from the Ohio State University, and is a registered Professional Engineer in the state of Texas. Jeff spent a number of years in hands-on roles as a process engineer and operations support advisor for gas plants, offshore platforms and other upstream operating facilities. Jeff has significant experience in the area of process safety, where he was the Leading Global Technical Authority for ExxonMobil’s Production Company.

Kelly Keim is Chief Process Safety Engineer (retired).Kelly Keim retired as chief process safety engineer from ExxonMobil Research and Engineering after over 33 years of service. Following 15 years in several levels of management in operations and maintenance, Kelly found his passion in process safety. In his final years, Kelly had the lead role in revamping ExxonMobil’s tools and methods for assessing and managing the risk of operating hazards with the highest potential consequences such as BLEVE, toxic releases and vapor cloud explosions. In October 2016, Kelly was recognized at the Mary Kay O’Connor process safety symposium at Texas A&M University, as part of a team receiving the Harry M. West Service Award for contributions made to the process safety center as well as the Trevor Kletz Merit Award for contributions to the field of process safety.

Mike Neill is President, Petrotechnics USA.With more than 35 years of experience, Mike has helped to improve safety and performance management for companies in hazardous industries around the world. Prior to joining Petrotechnics, Mike held roles in Operations, Drilling and Petroleum Engineering for BP Upstream, in Scotland, Norway, the South of England, and Egypt. Mike holds a BSc in Mechanical Engineering, MSc in Petroleum Engineering from Imperial College of Science and Technology at the University of London, and an MBA in Strategic Management from the Peter F. Ducker Graduate Management Centre, Claremont Graduate School in California. He is an active member of the CCPS, AIChE, ASSE, GPA, and the Mary Kay O’Connor Process Safety Center.

Greg Cline is Principal Market Analyst, Aberdeen Group.Greg Cline is an experienced analyst, consultant and business planner. As the head of research for Aberdeen Group’s Product Innovation and Engineering (PIE) and Manufacturing research practices, he covers topics related to development and manufacturing of products, ranging from new product development to embedded systems. Previously, Greg spent 17 years as a market intelligence manager and strategic product analyst at Intel Corporation, where he provided market insight to senior executives and managers. In addition, he spent a dozen years at globally-respected market research firms, such as Yankee Group, IDC Government, and In-Stat. Cline has an MS degree in Computer and Information Systems from Dartmouth College.