Norway in need of larger finds to sustain conveyor belt of projects

Simon Sjøthun

Rystad Energy

High-impact wells may be critical to sector’s future

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) recently summed up its review of activity on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) during the first half of the year by commenting that the 20 development projects in progress represent a record for the region. This underlines the status of the Norwegian sector, where cost improvements and project resource increases have led to these highly competitive developments going forward.

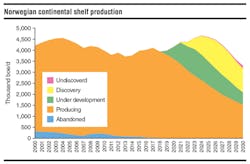

However, Norway’s short-term boom is clouded by a dearth of new projects after 2020 which will likely lead to a sharp decline in production from the mid-2020s onward. The question then is how to meet the strong growth ambitions from a vivid player landscape without the discovered resources needed to enable such growth.

The oil price downturn in 2014 called into question the continued competitiveness of offshore resources generally, and in particular those resources located in harsh weather conditions. The industry responded to the challenge by reducing costs and increasing the resource base for various projects, which resulted in an average reduction in breakeven prices between 20 and 40%, the same as for North American shale resources. Offshore resource therefore maintained their competitiveness in the global oil supply stack. The latest third-party valuation of the Norwegian State’s Direct Financial Interest, released in June, indicated that the portfolio managed by state-owned Petoro increased in value from NOK810 billion ($100 billion) to NOK1,093 billion ($135 billion), driven primarily by increased resources and lower costs.

Thanks to the new era of cost competitiveness, the various licensees were able to sanction the Norwegian projects currently under development. And the resulting project sanctioning activity on the NCS has been the highest in the world, in terms of offshore projects. Johan Castberg, Snorre Expansion, and Trestakk are all examples of projects that were struggling with high-cost, over-scoped concepts, and delays to sanctioning. Equinor, the operator in each case, was nevertheless able to get the projects through to the development stage at breakevens in the low $30/bbl.

Competitive resources also attract new players. The player landscape on the NCS has changed since the oil price drop with majors abandoning their operated positions in favor of dedicated NCS organizations furthering development of fields. At the same time, Equinor has also stopped divesting NCS resources and has instead used the downturn to grow its position via its acquisition of Total’s operated stake in the Martin Linge field and associated development in the North Sea, and through a farm-in with Lundin. Private equity too has extended its reach on the shelf with Neptune Energy and Point Resources making major acquisitions (VNG Norge and Engie and ExxonMobil’s Norwegian North Sea portfolio). Finally, there are also industrial players from the Middle East and Eastern Europe chasing growth on the NCS with Kufpec making acquisitions and Gazprom making a swap with OMV. Common priorities to all these companies are significant cash flow generation following the latest oil price surge and the ambition to grow further with significant investment capital at their disposal.

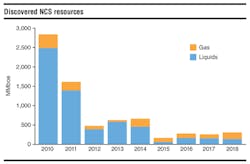

However, with poor exploration results offshore Norway since Lundin’s 2014 Alta discovery, the contingent resource base is diminishing along with the project portfolio. Average discovered resource per year since 2014 has been just 250 MMboe. The high-impact wells drilled in the Barents Sea in 2017 disappointed especially. With the influx of new players, growth ambition and capital, the limited project portfolio will likely force additional investments into existing fields to increase recovery and more extensive exploration. There have been early signs of this in 2018, while the NPD has reported a 1.2 Bboe increase in reserves from existing fields from year-end 2016 to year-end 2017 and booming exploration activity moving back toward the levels seen during the high oil price era, with around 50 wells per year. The latest Statistics Norway projection for 2019 exploration spend also indicated a further activity increase with spend forecast to rise from NOK25 billion ($3.08 billion) to NOK33 billion ($4.076 billion).

The increased activity has helped refill the project portfolio with 2018 exploration prior to this month delivering discovered resources of about 350 MMboe, already higher than all of 2017. These include potentially high-value discoveries at Hades/Iris, Frosk, and Lille Prinsen in the Norwegian Sea and North Sea. Several high-impact wells will also be drilled later in 2018 with the Mandal High area covering the 400-MMboe Oppdal/Driva prospect, Aker BP drilling the 250-MMboe JK prospect north of Johan Sverdrup (both in the North Sea), and Total drilling its 400-MMboe Jasper prospect in the Norwegian Sea. Despite a disappointing 2017 campaign, the Barents Sea will see high activity continuing in 2018 with the billion-barrel potential at the Gjøkåsen prospect as the biggest prize.

A high-impact exploration success with stand-alone development potential would be welcomed by all stakeholders from the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy to the oil service industry looking for its next big project. Back in the early 2000s, the NCS also faced a similar predicted decline, which ultimately did not materialize. It remains to be seen if history will repeat itself, but at least the industry continues to explore for the next high-impact discovery and chase increased recovery from existing fields, which ultimately is what is needed to arrest decline and alleviate worries about the long term.