Momentum building for final decommissioning of Greater Dunlin Area

North Sea operator looking to transfer experience to other projects

Jeremy Beckman

Editor, Europe

The Dunlin Alpha platform. (All images courtesy Decom Energy)

One of the UK North Sea’s widest-ranging and most complex decommissioning projects is progressing toward completion. Later this year Fairfield Energy, a subsidiary of Decom Energy, expects to submit its preferred concept for decommissioning of the Dunlin Alpha platform, and to initiate approved work programs for the Greater Dunlin Area subsea infrastructure. At the same time, plugging and abandonment (P&A) of the extensive network of platform and subsea wells will continue.

But the company is already looking beyond completion of this project, some time in the early 2020s, with the goal of applying the experiences and techniques it has developed since Cessation of Production (CoP) at Dunlin to take on other offshore operators’ decommissioning projects.

Dunlin Area history

Shell was the original operator of the Greater Dunlin Area, starting with the Dunlin field in blocks 211/23a and 211/24a, 195 km (121 mi) northeast of the Shetland Islands. In the mid-1970s the company commissioned the platform, which features a 320,000-metric ton (352,739-ton) concrete gravity base structure (CGBS). Four concrete legs extend from the CGBS to around 8 m (26 ft) below sea level, where they are connected to steel transition columns, in turn supporting a module support frame and a 15,886-metric ton (15,635-ton) deck. Production started in August 1978, reaching a peak of 120,000 b/d of oil the following year. Shell drilled the Dunlin and Dunlin South West wells using the platform’s rig, and during the 1990s, developed and tied back the Osprey and Merlin subsea satellites.

In 2008, when the Greater Dunlin Area facilities had already exceeded their design life expectancy, Shell agreed to transfer ownership to the newly formed Fairfield Energy. Over the next few years Fairfield proceeded to extend production further through a program that included improvements to well performance, restoration of the by-then idle platform rig, subsea modifications, infill drilling based on analysis of new 3D seismic, and installation of a fuel gas import pipeline from the Thistle A platform for power generation at Dunlin A. However, the growing costs of maintaining the various production facilities and the need to address integrity issues with the platform conductors – at a time when the oil price was starting to plummet – led management to apply for permission to terminate production. This duly occurred in June 2015 following agreement with regulators that maximum economic recovery had been achieved after 37 years of production.

Wholesale UK North Sea decommissioning of larger fields and platforms was at that point in its infancy, with few contractors offering specialist capabilities aside from topsides removal. In view of the sheer scale of the program ahead at the Greater Dunlin Area, Fairfield’s team realized it would need to develop a new organization with different skills focused largely on decommissioning (as opposed to late-life production). The company then garnered support from the UK’s Oil & Gas Authority for the transition in status from production to decommissioning operator – a move aimed at securing its long-term future as a specialist decommissioning organization under new parent company Decom Energy.

The next priority was to staff the new organization to plan and manage the upcoming program. According to Decom Energy’s Managing Director Graeme Fergusson, the current leadership and senior technical staff are largely unchanged, aside from the subsurface team which had to be released. Some individuals were also recruited with specific expertise more relevant to P&A and subsea decommissioning work. “We had no experience internally in terms of removal engineering,” Fergusson explained, “so we reassigned our experienced management team to focus on the asset’s decommissioning, and supplemented this with external expertise and support where necessary. At the same time, it was important to keep control over the project. We had operational people who knew the asset well, but who also needed to learn about what lay ahead in terms of the full decommissioning scope. To a great extent, our people have educated themselves over the past three years and the results have been impressive.”

The original plan had been to start P&A of the 45 platform wells in early 2016, with work on the first of the 16 Merlin and Osprey subsea wells to follow later that year. However, it soon became apparent that the scale of this program would create capacity risk in terms of the Wells and Subsea Abandonment team and the support organization. Management responded by deferring the start of the subsea campaign until spring 2017.

Project’s current status

The Greater Dunlin Area project has been split into five main components: decommissioning of the Dunlin A platform; removal of the subsea infrastructure; ‘make safe and handover’ of the production facilities; platform-based P&A; and subsea P&A. The current status, according to Fergusson, is as follows:

Dunlin A decommissioning. The four options remaining are removal of all facilities down to the seabed; all facilities above the water line; and two other solutions in-between. “We are looking to submit the proposals for decommissioning of Dunlin A in the next few months. We have held extensive discussions with the regulators and stakeholders on the various options and what may or may not be involved. To an extent, we have been able to draw on the experiences of other operators decommissioning platforms with gravity based structures, and in particular what Shell has done at the nearby Brent field.

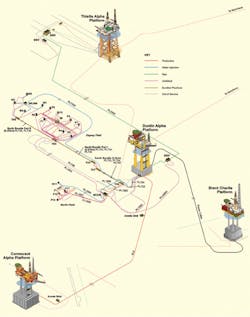

Overview of the Greater Dunlin Area production and export facilities.

Subsea infrastructure. This comprises the drilling templates, manifolds, pipelines and bundles which tieback the Osprey and Merlin developments, respectively 6 km and 7 km (3.7 and 4.3 mi) northwest of Dunlin A; the fuel gas import pipeline from Thistle Alpha; and a power import cable between the Brent C platform and Dunlin A. Three associated decommissioning programs were all approved late last year following agreement with the regulators on what seabed structures could be decommissioned in-situ. Following imminent contract awards, this work should be executed between mid-2018 and mid-2019.

Make safe and handover. “Under a long-standing service agreement, live hydrocarbons are still flowing across the asset from Thistle Alpha,” Fergusson said, “and we are keen to keep this arrangement going as long as possible, while doing the minimum amount of work necessary in the run-up to decommissioning of the platform. But we have had to make changes to commercial arrangements drawn up in the 1970s, which did not consider the ramifications of the asset ‘expiring.’ Preparing the facility for decommissioning is the other main task: Dunlin A is not suited to a single-lift removal of the deck, and will therefore require a combination of reverse installation and other piece small lifts.

“One special area of focus is the conductors beneath the module support frame: these have become damaged over time and have had to be bolted, braced and clamped in various places, so recovering to the deck may not always be feasible. We initially found that there was not a great deal of expertise out there to address this problem, so we engaged with the UK’s offshore supply chain at various decommissioning ‘share fairs’ and with engineering specialists outside the offshore oil and gas domain in an attempt to find a solution. The technical challenge has been embraced and a number of techniques will be applied to safely remove the conductors, integrating with the platform P&A campaign and reducing the overall duration that Dunlin A will be manned.”

Platform P&A. The phase 1 program started in early 2016 with slickline work while the platform rig was reactivated. “The Dunlin platform wells present a complex challenge due to their age and the poor condition of the annular cement,” Fergusson explained. “We conducted extensive studies and trials early in the program on the use of novel methods to address these issues, but none were found to be suitable for the wells’ specific architecture. As the well abandonment progressed, however, and the team increased its knowledge of the status of the wells, we were able to undertake subsurface analysis and flow modeling to evaluate the tolerance of individual plug failures. This reduced the work scope and the cost of each well abandonment. There has also been a focus on ‘evolution rather than revolution’, making use of the latest advances in established technology and driving efficiency in each part of the operation.” An Archer crew is operating the platform rig, with Exceed providing engineering support, although Fairfield remains the technical authority for the campaign while ensuring integration of the work with the wider project.

3D model of the Dunlin A platform, conductors and concrete gravity base.

Subsea P&A. The semisub Transocean 712 mobilized to the Greater Dunlin Area last April to start P&A on Osprey’s 12 subsea wells, and the program should finish this summer. The rig will then start on Merlin’s four wells, with the work likely to be completed by early 2019. “In order to access the subsea wells, the original intervention equipment - stored from the time the well completions had been installed – required extensive refurbishment and testing,” Fergusson said. “At this time the equipment was also modified to allow the rig to move between wells without the requirement to recover the equipment to surface. This modification facilitated a batching approach to the subsea wells, resulting in increased efficiency through minimizing weather-sensitive operations. The age of the Osprey subsea trees meant they were designed for diver-based intervention. Working with our suppliers, however, we have been able to design and deploy ROV tooling to interface with the subsea trees, eliminating the majority of the diving work scope and reducing cost.”

Late-life model

“We believe we are the only operator focused entirely on decommissioning, with no pressure of production,” Fergusson said. “If we’d continued to produce from the Greater Dunlin Area it would have been sub-economic, but being able to focus entirely on decommissioning has got us so much further down the line.”

The company is already looking beyond completion of this project, he added, and has held talks on applying its experience to other UK offshore late-life fields. “We are offering a comprehensive service: we believe we can take over an asset, run it to the end of production, and then decommission it. Within the next 12-18 months we hope to win our first project: for some companies, the idea of handing over full responsibility for an asset is a big step, almost like a merger and acquisition process, and it will require additional resources. But we are confident we can apply our experiences from the programs at Dunlin, Merlin and Osprey – which are about as complex as it gets - while at the same time building our knowledge of the acquired asset to determine what needs to be done for decommissioning.

“Our offering covers the whole process and could entail taking over at CoP when the asset has stopped producing, or optimizing the ultra-late life phase when there are no more wells to drill and the asset is in perpetual decline – perhaps spending the final years maximizing the remaining production, while starting to P&A the platform wells so that the decommissioning process is as efficient as possible when the taps are finally turned off.”

According to Fergusson, UK North Sea operators of all sizes have shown interest in this approach. “We hear regularly from companies that they do not want to take on decommissioning themselves. A lot of the ‘big boys’ have already been heavily outsourcing this process, although there are exceptions such as at the Brent field where Shell has been heavily involved. But I do think the market is ready for innovation, and the Oil & Gas Authority has been highly supportive of what we’ve been doing and keen for our model to succeed. They see our experience as a learning curve that may inform the rest of the North Sea.”

Some of the lessons learned from the program on the Dunlin A platform in particular could be applied to minimize costs in other projects. “We have always looked to challenge the conventional way of doing things,” Fergusson said. “Initially during the P&A process, we were installing three 200-ft [61-m] barriers per well, but it was taking a long time. So we reviewed the regulations and wondered, do we really need to do this from a risk point of view? The answer was ‘no’, so we switched to a single 200-ft barrier and two 100-ft [30-m] barriers: the resultant gains have saved us upward of £25 million [$36 million].

“We have also looked to implement SIMOPs where possible. During the project’s early phase in 2015-16, we identified a need for an integrated approach. There were 140 beds on the platform and a big drilling crew: by prioritizing the safety-critical processes, we determined we could bring the crew compliment down to 50, focusing on what really needed to be done – not what used to be done – and this too has led to substantial efficiencies.”

Taking on other North Sea projects would necessitate recruitment of extra staff, Fergusson said. “We don’t see ourselves owning specialist equipment such as heavy-lift vessels or drilling rigs, but we are open to alliances with other contractors, depending on whether the operators we engage with want a ‘packaged’ solution. We have built relationships with Archer and Transocean on Dunlin, and WorleyParsons engineers have provided expertise on the topsides work. Could we take these relationships forward to other projects? It is possible.

“Our next project has to be in the UK North Sea, and probably involving one of the larger installations in the central or northern sectors. Beyond that, there is no reason why we could not transfer this service to other types of assets on the UKCS and also farther afield. We have had enquiries from Brazil and Australia, where there are several offshore concrete gravity based structures.”

There remains the question of finance, but Decom Energy is flexible as to how this might be structured, recognizing that each deal is likely to be different. “We are looking at a variety of commercial models to ensure alignment with existing owners, aimed at reducing overall cost and providing certainty. The UK government’s recent decision to transfer tax history for fields approaching decommissioning also opens the way to new potential models,” Fergusson concluded.