John Pappas

Chadbourne & Parke LLP

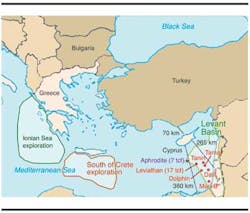

As Greece searches for a solution to its unending debt debacle and Cyprus seeks €5.8 billion ($7.6 billion) for its European bailout, both countries' best hope may lie under their very shores. In the past four years, fortunes in fossil fuels have been unearthed in the eastern Mediterranean. In April 2010, the US Geological Survey estimated 122 tcf of recoverable natural gas in the eastern-most part of the Mediterranean Sea (the Levant or Levantine basin), more than the world consumes in a year. If this and other estimates are correct, these offshore natural gas and oil deposits may play the deus ex machina to the current Greek drama.

Although parts of the Mediterranean Sea have been explored for many years, new technologies that allow highly sensitive underwater surveying and deeper offshore drilling have exhumed previously inaccessible reserves underneath the sea. Cyprus, for example, may hold 7 tcf of natural gas, which according to Cyprus' own commerce minister may be worth €100 billion ($131 billion). These figures have led some to speculate that Cyprus may lease or sell the rights to its newly discovered natural gas and oil to pay off its debts. A recent visit by Cyprus' finance and energy ministers to Russia to discuss debt solutions certainly helps fuel those whispers. Yet Cyprus was not the first place in the Mediterranean to unearth oil and gas.

Israel's initiation

It all started offshore Israel. Noble Energy, a Houston-based oil and gas company with Israeli ties, led the exploration of oil and gas in Israel's waters in the Levant basin. There Noble first discovered the Mari-B field, the first offshore natural gas production facility in Israel, which began production in 2004. Then Noble moved farther offshore discovering the fields Tamar in 2009 (9 tcf); Dalit in 2009 (0.5 tcf); Leviathan in December 2010 (17 tcf – enough to supply Israel's gas needs for 100 years); and Dolphin/Tanin in February 2012 (1.2 tcf). To put these amounts into perspective, in 2011 the three largest natural-gas consuming countries consumed 24.3 tcf (the United States), 17.9 tcf (Russia), and 5.4 tcf (Iran).

The Leviathan gas field is Noble Energy's largest find, and Noble retains a 39.66% working interest, sharing with Avner Oil and Gas (22.67%), Delek Drilling (22.67%), and Ratio Oil Exploration (15%). Leviathan is predicted to start production in 2016, while Tamar, the second-largest find in the Levant basin, began production this past March. Along with natural gas, Noble Energy also estimates that Leviathan could hold up to 4.3 Bbbl of oil. Israel has long depended on foreign sources for its energy needs, making these finds very welcome news. Gideon Tadmor, chairman of Delek Drilling and chief of Avner Oil, both subsidiaries of Delek Energy Systems, said in a New York Times article that these offshore natural gas discoveries have "enabled Israel to enter a new era in which we will become an exporter of energy."

Cypriot second wind

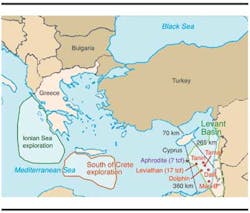

While developing its Israeli finds, Noble Energy also eyed the waters of Cyprus. In October 2008, Noble Energy received the exploration rights off the southern coast of Cyprus to block 12 of Cyprus' maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). After beginning exploratory drilling in September 2011, Noble discovered the Aphrodite gas field. This find is 21 mi (13 km) west of the Leviathan gas field. It is believed to hold 7 tcf of natural gas, more than Cyprus could consume in a century. Noble shares ownership of the well (70%) with Delek Drilling (15%) and Avner Oil Exploration (15%), the same partners in the Leviathan field. The country's Commerce Minister, Praxoulla Antoniadou, estimated that 7 tcf of gas in block 12 is worth around €100 billion. In fact, Solon Kassinis and Charles Ellinas, heads of the Cyprus Natural Hydrocarbons Co. (CNHC), have both said that Cyprus envisages having more than 60 tcf of total gas reserves in its EEZ. This too comes as welcome news to a debt-ridden and cash-strapped Cyprus.

In February 2012, Cyprus announced a second licensing round for the remaining 12 out of 13 blocks of Cyprus' EEZ. On Jan. 24, 2013, Cyprus licensed a consortium including Italy's Eni and South Korea's KoreaGas Corp. (Kogas) to explore blocks 2, 3, and 9 of Cyprus' EEZ. Additionally, on Feb. 6, 2013, France's Total paid Cyprus €24 million ($31.6 billion) for the license to explore blocks 10 and 11. Total announced it would conduct a series of 10 exploratory drillings for gas and oil over the next three years. It is thought that it will focus mainly on oil. It will likely take these companies until 2018 to produce oil and gas for domestic consumption and 2019 for export.

Pipelines versus LNG

The greatest debate surrounding the Leviathan and Aphrodite discoveries is how to transport the oil and gas to market. There seem to be four possibilities on the table: a pipeline to Turkey; a pipeline to Greece; a liquefaction plant in Cyprus; and a floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) vessel.

The first option is politically complicated. Building a pipeline to Turkey that would feed into existing pipeline infrastructure to Europe could be the most cost-efficient choice. However, Turkey has already decried Cyprus' offshore exploration, claiming the waters as its own, threatening to cut participating energy companies from access to Turkey's market, and sending a warship into the area after test drilling started in 2012. Even if Cypriots and Turks could agree on the rights to the Aphrodite oil and gas, Cypriots worry that Turkey will, like Russia, use the gas valves for political ploys.

As for the Israelis, Turkish relations have been similarly strained; at least they were before March 22, 2013. On that day, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu publicly apologized to Turkish Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan for Israel's 2010 raid on the Turkish shipMavi Marmara that resulted in the death of nine Turkish activists seeking to bring aid to Gaza. Israel may have extended this olive branch to facilitate warmer relations between Israel and Turkey on the Syrian issue, and to smooth the possibility of a potential pipeline to bring natural gas from Leviathan to Europe through Turkey. However, while this public statement may ease tensions between the two countries, the threat of Turkey turning off the pipeline in the future remains; and there is also the unending Palestinian impasse (Turkey supports Palestine). Thus although possible, a pipeline through Turkey remains problematic.

The second option would entail constructing a pipeline from Cyprus to Crete and from Crete to Greece, connecting then to existing pipelines throughout Europe. However, this option appears to not be commercially viable. At least that seemed to be the conclusion at the 2nd Cyprus Energy Forum in December 2012. Solon Kassinis, vice president of the CNHC, hinted that this idea has been all but abandoned. The main concerns appear to be the high construction cost, long construction time, falling electricity demand and prices in Europe, and the necessary long-term supply contracts that would be linked to the price of oil.

The third option consists of constructing a liquefaction plant in Cyprus, where the natural gas from both the Leviathan and Aphrodite fields could be liquefied and shipped. The major benefit of this option is that the LNG can then be shipped to a variety of markets (Europe as well as Asia), garnering higher prices on the spot market. The largest drawback however is the price tag – LNG terminals typically cost about $10 billion (as compared to $1 billion for a Cyprus-Turkey pipeline). Kassinis explained at the 2nd Cyprus Energy Forum that Cyprus was contemplating an LNG facility with up to three trains for a total capacity of up to 15 MM tons/yr. An LNG train is a liquefaction and purification facility, which typically has capacity for 5 MM tons of natural gas a year. For those wondering about constructing an LNG plant in Israel instead of Cyprus, this option appears impractical because of limited space, environmental concerns, and security problems in Israel.

The fourth option is mooring a floating LNG vessel at Leviathan and Aphrodite. On one hand, this option has great advantages – exportable LNG and lower cost relative to a pipeline to Greece – but on the other hand the technology is new and untested. There are also fears that the vessel would be vulnerable to terrorism.

While no option has definitively been chosen, recent developments suggest that an LNG plant in Cyprus will win the day. Cyprus has announced plans to build the Vasilikos LNG Terminal at the Vasilikos Energy Centre, which already serves as an energy hub on the island. It seems that the CNHC and Noble Energy are waiting for final confirmation of block 12 reserves before potentially entering into a joint venture to build Train 1 of the LNG terminal. They should have this confirmation by the end of 2013. Subsequent trains will depend on the extent of more natural gas finds. It is not clear whether Israel will choose to connect its Leviathan field to the Vasilikos LNG terminal. While it has achieved some sort of rapprochement with Turkey, suggesting that it is contemplating building a pipeline to Turkey, such a pipeline would also pass through Lebanese and Syrian waters and require those countries' approval. Considering this and the other shortcomings of a Turkish pipeline listed before, it is likely that Israel will connect to the Vasilikos terminal any natural gas that exceeds its domestic needs.

Greek hopes

These oil and gas discoveries in Israel and Cyprus are also providing inspiration to those Greeks who hope to drill themselves out of debt, and lessen Russia's natural gas grip over Europe. "It is important that Greece returns to the energy map again," said Energy Minister Evangelos Livieratos. "Our country can attract new investment, create new jobs, and boost its geo-strategic position and competitiveness to exit the crisis." In 2012, one study by Athens-based Flow Energy estimated €600 billion ($787.9 billion) worth of offshore natural gas in Greece over 25 years. This study discovered geological similarities between the Levantine basin and offshore Crete. In the waters south of Crete, the study estimates 3.5 tcm (123.6 tcf) of natural gas, enough to cover over six years of EU gas demand, and 1.5 Bbbl of oil.

Still others estimate that total offshore oil in Greek waters exceeds 22 Bbbl of oil in the Ionian Sea and some 4 Bbbl in the northern Aegean Sea. Evangelos Kouloumbis, former Greek Industry minister, recently stated that Greece could cover 50% of its needs with the oil to be found in offshore fields in the Aegean Sea. Highlighting how unexplored Greece is regarding hydrocarbon potential, one Greek analyst, Aristotle Vassilakis, cited surveys that estimate $9 trillion worth of natural gas. Tulane University oil expert David Hynes told an audience in Athens recently that Greece could potentially solve its entire public debt crisis through development of its new-found gas and oil, conservatively estimating that reserves already discovered could bring Greece more than €302 billion ($396.5 billion) over 25 years.

Despite the touted potential of oil and gas in Greece, it is important to remember that almost 200 fruitless test wells have been bored in various parts of Greece in the past century. The most recent one was approximately 12 years ago. However, those who are optimistic about Greece's energy potential respond that most of the tests were badly managed or carried out at the wrong locations. Right now, Greece spends €10-12 billion ($13-15.7 billion) a year on oil imports, about 5% of its GDP. This dependence on foreign oil, coupled with its need for financial solutions, might make oil and gas Greece's silver bullet.

On Nov. 11, 2012, the Norwegian Petroleum Geo-Services ASA (PGS) began a three-month long seismic survey of the Ionian Sea and water south of Crete, an area that covers a total 220,000 sq km (84, 942 sq mi), an area 40% larger than mainland Greece. By mid-2013, the survey analysis should be complete, and in the first half of 2014 Greece plans to hold a licensing round for exploration blocks. However, before holding a licensing round, Greece would also need to establish an EEZ, a move it has yet to undertake.

Other Mediterranean hopes

In addition to Israel, Cyprus, and Greece, other Mediterranean countries are interested in exploring for natural gas and oil. Incited by the finds of their eastern neighbors, Spain and Italy are looking into offshore exploration. "There is a lot of potential, we believe, in the Mediterranean region," said Simon Thomson, chief executive of Cairn Energy of Britain, which is exploring off the coast of Spain and bidding for licenses in Cyprus. "A lot of hydrocarbons have already been discovered, but we believe there's a lot more to be discovered."

Expressing the same sentiment, petroleum geologist David Peace told Reuters that "[i]f you look at the offshore license map of Italy, about two-thirds of it is open…Italy is one area that has been overlooked, especially the south." To facilitate these efforts, Italy is relaxing its ban on offshore drilling, placed after the 2010Deepwater Horizon spill.

More specifically, there appears to be interest in the waters around Malta, with geologists believing that the oil-rich geology of nearby Libya extends northward underneath the sea. The prospects are strong enough that Genel Energy (headed by former chief executive of BP Tony Hayward) has partnered with Bill Higgs (chief executive of London-based Mediterranean Oil and Gas). The company hopes to finish drilling its first well in the area by the end of 2013.

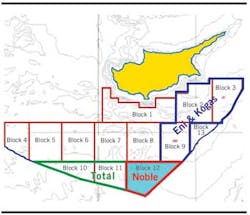

Natural gas in Europe

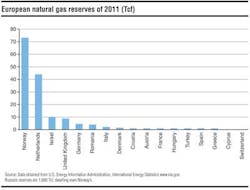

To compare the figures in Israel, Cyprus, and Greece to Europe, one needs to review the natural gas production and consumption among European countries and the reserves of natural gas these countries hold. For this analysis, all figures were taken from the Energy Information Administration's website. Norway clearly leads the continent in natural gas production while also having a very low degree of consumption. The Netherlands and United Kingdom are the only other two significant producers, although production in the UK has declined significantly over the past four years. As a comparison, one could note that in 2011, Russia produced 23,686 bcf, more than six times what Norway produced. The major consumers of natural gas are the UK, Germany, Italy, France, Turkey, the Netherlands, and Spain. In general, consumption seems to have declined in the past four years, especially in Germany, except in Turkey, which shows an upswing in consumption in 2011. Lastly, Norway and the Netherlands lay claim to the largest reserves in Europe by far, although Russia's 1,680 tcf in reserves dwarfs that amount.

The author

John Pappas is a Project Finance Associate in the Washington, D.C., office of the law firm Chadbourne & Parke LLP. He is a member of the New York Bar and the Energy Bar Association, and can be contacted at [email protected].