Editor's note: This story first appeared in the September-October 2022 issue of Offshore magazine's first annual Offshore Wind Special Report. Click here to view the full Offshore issue or click here to view the special report.

By Cinnamon Edralin, Esgian

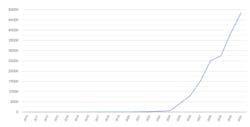

The US offshore wind industry is facing some challenges and opportunities unlike those seen in other parts of the world. Currently, Asia-Pacific has the most operational wind farms at 146, followed by Europe with 114. The US has only two—the 30-MW Block Island project off Rhode Island and the 12-MW Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind pilot project. However, in terms of installed generation capacity, Europe takes the lead with 27 GW versus nearly 25.7 GW for Asia-Pacific. The US comes in at only 0.042 GW.

In March 2021, US President Joe Biden established a national target for offshore wind of 30 GW by 2030. To meet this goal, rapid expansion is needed. However, the Jones Act, which is intended to protect US jobs, has led to some unintended consequences that will put added pressure on the burgeoning offshore wind industry to achieve the president’s goal. The Jones Act deals with coastal trade and requires that all goods transported via water between US ports must be done on ships that are US-built, US-flagged, US-owned and crewed either by US citizens or permanent residents.

Because of the complexity and tonnage being transported and installed, offshore wind requires specialized vessels. Most of the existing fleet of wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs) and other heavy-lift vessels are busy working off Asia-Pacific or Europe, where most of the offshore wind projects are currently being installed. These vessels are not Jones Act-compliant and would require a waiver, which are generally difficult to obtain, to work off the US coast. Notably, cable installation vessels are not subject to Jones Act restrictions, so vessels from elsewhere would be able to work in US waters.

If project operators are unable to bring existing vessels into the US, an option would be to construct Jones Act-compliant vessels in the country. However, few US shipyards are equipped to build the specialized vessels needed for offshore wind farm installation. At present, the only WTIV being built in the US is the Dominion Energy-owned Charybdis, which is under construction at Keppel AmFELS in Brownsville, Texas, at an approximate cost of $500 million. The unit will also be capable of installing foundations. It is scheduled for delivery by year-end 2023 and will be operated by Seajacks.

To give some context to the cost to build a Jones Act-compliant vessel, newbuild costs for WTIVs in other locations, such as China, run about $350 million. This difference significantly raises the cost of US projects. When added to the high costs for being paid for acreage, this potentially places pressure on developer margins and puts a squeeze on other suppliers to try to keep overall rates of return up.

Further complicating the situation is the pending merger between Singapore-based companies Keppel Corp. and Sembcorp Marine. If finalized, it is not yet clear what the forward plan is for the Keppel AmFELS division. A new name and brand identity for the combined company will be adopted post-merger.

Meeting installation targets

Given the current state of the global economy, costs are on the rise, and lead times for parts and equipment are growing. This means any new vessel orders are likely to come at a higher price tag and will take longer to deliver. With Esgian’s Wind Analytics database reporting 34 US offshore wind projects in the planning stage, project operators will need innovative solutions to meet their installation targets.

One out-of-the-box option for navigating Jones Act compliance comes from Maersk Supply Service, which now has two turbine installation contracts for the Equinor and bp joint venture (JV) projects, Empire Wind and Beacon Wind, both located on the East Coast. This vessel is designed to work using a feeder method in which this vessel will remain on location while support vessels transit between it and the shore. Delivery is expected in 2025. In conjunction, Kirby Offshore Wind will build and operate the associated tugs and barges in the US, thus ensuring Jones Act compliance.

Meanwhile, new areas for offshore wind continue to open and many more projects are expected to be announced. The US East Coast, with more than 10 GW of projects on the books, is further along in terms of planning and development than the West Coast, for which the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) is progressing a Call for Information and Nominations for two areas off Oregon, and the public comment period for the California Proposed Sale Notice closed on Aug. 1. Meanwhile, BOEM only began accepting comments on two draft Wind Energy Areas in the Gulf of Mexico in the latter half of July. However, given the local shorebase experience and port infrastructure related to offshore oil and gas, this region of the US is probably best prepared to begin work related to offshore wind.

California floating wind tech

California, which does not have any operational offshore wind farms yet, has set an aggressive target. In August, new goals of up to 5 GW by 2030 and 25 GW by 2045 were set by the California Energy Commission. The Humboldt and Morro Bay Wind Energy Areas are the state’s first federal water areas to begin the BOEM’s leasing process.

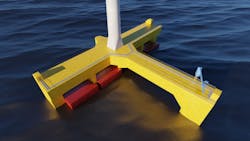

Because of the state’s steep descent into deep waters, floating technologies will need to be adopted earlier on than other locations that have more shelf area to pursue the more-tested fixed technologies. Globally, there is not yet a consensus as to the most preferred floating technologies, and most are still in the test, or pilot, phase. The number of floating projects needed to meet the state’s goal could provide an opportunity for California to help narrow the list of preferred floating technologies that end up being adopted on a global scale.

One floating project under consideration is the 150-MW Redwood Coast Offshore Wind project. The proposal anticipates five to 15 turbines that would be anchored to the seafloor by synthetic mooring lines in water depths ranging from 2,000 ft to 3,600 ft. An extra challenge for floating projects off California is that the ports are not configured to handle the size and weight and would need to be reconfigured.

Equipment lead times

Besides growing lead times for installation vessels and operation, maintenance and service vessels, manufacture of the associated foundations, turbines and cables also will be a challenge due to lack of sufficient US factories to meet the growing demand. Having to import these items will add to the project time and cost, as US projects would be competing with European projects also working toward ambitious targets. Plus, there would be an associated increase in emissions related to the transport of the equipment from further away. Meanwhile, converting existing US facilities or building new ones would mean a waiting period before production could start. Also complicating equipment matters is the ongoing legal dispute between US-based GE and Denmark’s Siemens Gamesa related to turbine patent infringement. At the time of writing, it appears an agreement may be reached that will allow the order for the Vineyard Wind project on the East Coast to move forward, but the fate of other projects with GE Haliade-X turbine orders are still in question.

Addressing the worker shortage

To address the issue of not enough experienced personnel in the US, a number of joint industry and local government initiatives have recently been announced. In early August, Rhode Island Governor Dan McKee and officials from Ørsted and Eversource announced a training program in partnership with the Community College of Rhode Island, the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, Rhode Island Commerce, the Rhode Island Building and Construction Trades Council, and Building Futures. Trainees will earn a Global Wind Organization certificate upon successful completion of the program.

In Maryland, the Department of Labor was one of the winners of the US Department of Commerce’s Good Jobs Challenge with a plan to implement an apprenticeship model for the offshore wind industry in partnership with multiple employers and unions. The focus will be on training underserved populations, such as formerly incarcerated individuals, veterans and disconnected youth.

US versus Europe

In Europe there continues to be a push toward using floating wind power in the decarbonization of oil and gas projects. This is driven primarily by government targets to significantly reduce carbon emissions (by 50% by 2030) and finding a balance between that reduction and increasing demand for hydrocarbons in the region due to the ever-deepening threat to energy security following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Equinor led the way with the development of the 88-MW Hywind Tampen floating project, which is expected to provide about 35% of the annual electricity power demand for the five platforms located on the Norwegian Snorre and Gullfaks fields. Installation of the first turbines has already begun with the process expected to be completed next spring.

The same operator is continuing to push ahead with a similar project by beginning a study into building a floating wind farm, Trollvind, to power the Norwegian Troll and Oseberg fields. Partners in the project hope that power from Trollvind could make a solid contribution toward electrification of oil and gas installations, accelerate offshore wind development in Norway and deliver extra power to the Bergen region.

Over in the UK, Orcadian Energy announced earlier this yearits intention to utilize a floating wind turbine in its development of the Pilot Field. The concept proposes the use of Floating Power Plant’s FPP Platform, which will hold a 12-MW turbine and a 2-MW integrated wave power generator. The scope of the project includes 34 wells to be drilled by a jackup through a pair of wellhead platforms and provision of power from a floating wind turbine. It is anticipated that this development plan will mean that Pilot emissions will be at the low end of the lowest 5% of global oil production emissions.

Ping Petroleum also outlined a floating wind project to reduce emissions at its Avalon development. In partnership with Cerulean Winds, the JV will operate one floating wind turbine to power the Sevan Hummingbird FPSO to reduce diesel and fuel usage. This will be one of the first projects to meet the UK government’s emission reduction targets.

Decarbonization projects

With that in mind, the UK expects to see more projects in the near-to-medium term, especially in light of the upcoming Innovation and Targeted Oil and Gas (INTOG) decarbonization process. INTOG could add a further 4 GW of new offshore wind capacity just in Scotland, and it is likely most projects will be situated west of Shetland where, incidentally, some of the most controversial oil and gas developments are expected to kick off in the next few years. It is hoped, should the INTOG process prove successful, other jurisdictions will follow similar processes. Indeed, Ping Petroleum will be applying for an innovation license under INTOG to allow for the operation of the planned floating wind turbine.

Despite the positivity and upcoming innovations in the floating wind market, however, the supply issues that plague the rest of the offshore energy industry are also affecting such projects. The aforementioned Hywind Tampen also has been affected. Equinor specified that supply bottlenecks, most notably in the steel market, will cause a delay in the final four turbines to be installed on site. It was found that the steel quality in the final four tower sections showed deviations and so, with corrections underway, delivery will now be too late to meet the Norwegian installation weather window for this year.

Overall, and aside from ongoing supply issues, it is likely the market will continue to see such decarbonization projects both within the North Sea and globally as operators seek to fine tune the balance between hydrocarbons and renewable energy in difficult economic conditions.