FPSO overruns present opportunity for change

Peter Lovie

Peter M. Lovie PE, LLC

For as long as I can remember, FPSOs have been stuck with a bad reputation for running over on budget and often on schedule, even though billions of dollars continue to be invested each year in these facilities, while very talented people manage the FPSO building and operating companies.

And, each year, FPSOs become more complex and vastly more expensive for many projects. This is a story of how these overruns can be hazardous to corporate well-being, and how these dangers have not gone away.

People often don't like to openly discuss this topic and name names - it can get embarrassing to corporate reputations. Accordingly, names are generally not mentioned here, although those that have been in the business for a while will recognize the players in what is intended as a professional addressing of the real situation, based on observations over the years.

But, the growing maturity and sophistication of end users and leading FPSO contractors may now combine to cause steps to mitigate and even cure the malady.

Not a new phenomenon

Fifteen years ago, five years into a commercial and engineering career with a leading FPSO contractor, I was asked to diagnose what was going on with cost overruns for three successive FPSOs that had been designed, built, and operated by my employer. The overruns were successively larger, the opposite of what one would normally expect. In general, three similar projects in a row would enable learnings from one to the next. I went through the entire business process, from business development and contracting on through all the engineering and construction processes and histories, on into installation and operation. I interviewed scores of people and conducted workshops to uncover what could be done to fix the situation the next time around. It soon became clear there was a need for rigorous consistent management control. There was nothing exotic about it; a lot of good people gave the projects their best shots. But someone in management needed to examine progress at major steps in the construction process and steer a different course, and/or take corrective action as needed. Achieving that was not at all easy. The principles of "gates" are widely recognized today but not so much 15 years ago.

Back in 2000, presentations from Independent Project Analysis Inc. (IPA) had highlighted how the performance of FPSO projects was often worse than other construction projects in terms of overruns on cost and schedule. We thought our company was better than that, but it was not really that way: better than some, but we did not avoid the problem. I doubt our competitors were immune from it either.

Nowadays at the Offshore Technology Conference in Houston and at more focused conferences aimed at the FPSO community, the discussion continues on project performance on FPSOs, and the story is much the same: the pattern of overruns continues, and still the FPSO contractors do not seem to fare much better in the industry perception.

Hazards to corporate survival

The pattern of FPSO overruns affects corporate growth. If not corrected, it can even undermine the viability of FPSO contractors. In some instances, it has led to mergers and change in corporate control.

The frantic growth of 2007-2008 led to published overrun problems for Prosafe and BW Offshore, contributing to their corporate merger. It was not as if all the managers at FPSO contractors were incompetent. They were highly skilled in what they did, but the limited number of projects they had to deal with simply had not been enough to foster building a team well able to manage and control projects, and that also was endowed with a will to do it right or not at all. Easy to say and very difficult to do: These project management disciplines have been underestimated in criticality in the past. Today, they are increasingly recognized as important within the big three FPSO contractors that have emerged (BW Offshore, Modec, and SBM Offshore).

In 2011, another FPSO contractor with a quite remarkable record of pioneering and fast growth got trapped in a major overrun in an FPSO redeployment. It led to a controlling interest being negotiated with another FPSO contractor with strong shipping ties (see industry news stories about Sevan and Teekay). Project overruns were not the only reason for these events but were a significant contributing cause.

Then there is the long-term insidious effect on financial strength: a cost overrun on a leased FPSO means the owner has to accept that return on capital employed (ROCE) for that asset may not be 11.5-12.0% over several years, but may become half of that. Assumptions used on residual value can similarly become dangerous.

Human nature

If you have done your time in business development as a contractor, you know how the pressure is there to nail down a contract and do it ahead of the competition. It is all too easy (up and down the management tree) to turn a blind eye to modest compromises in terms and scopes to make the deal. Staying strong to make the deal fundamentally sound long term is not at all easy.

On the operators' side, we have the management pressures to compress the cycle time to project completion and production, with the project NPV figures deteriorating if delivery stretches. Again, it is not always easy to hold one's ground. Tinges of mistrust surface in the heat of it all. Competitive, strong personalities are there on both sides of the table, coupled with ambitious statements made to boards of directors about achieving goals.

It is to the credit of operators and the major contractors that discussions in front of the FPSO community are now happening on these behaviors that so many of us have seen. This is a sign of a growing maturity to tackle difficult interests.

Business risks

The business risks are not getting any easier. The FPSO business is an inherently risky game, like many in the oil patch. Here are just a few of the challenges:

• Larger and more complex projects coupled with higher standards on safety and operability

• Difficulties in operating in remote areas, e.g. getting people into West Africa in the face of the Ebola epidemic, piracy, and so on

• Contract requirements for local content, local currencies for projects, use of multiple contracts for the project, all the while steering clear of FCPA exposures

• Vagaries in commodity prices (steel in particular) and in equipment suppliers worldwide for multi-year contract terms

• Lender demands for full payout contracts and risk mitigation for the hazards above.

Financial returns

Financial returns from owning and operating FPSOs historically have been dismal. Compared to other publically owned offshore and petroleum service businesses, FPSO names have been far behind in profits with zero or slightly negative percentages of revenues in recent years. There is no doubt that FPSO fleet trends are generally upward in demand, consuming a huge amount of capital. It is a competitive business, but compared to the offshore drillers that also are highly capital intensive, decent margins have not been there for years.

The oil company end users of FPSOs and the shipyards building them often do better in their financial performance.

FPSOs are not as repeatable as drillships. This fact underpins the unpredictability of FPSO business. Suffice it to say that it is difficult to build these huge vessels in one part of the world, with equipment from vendors all over, and still expect that the all the pieces will be delivered on time for operation in some remote part of the world to produce for years, sometimes from different oilfields. The risk of overruns becomes part of that low financial performance.

The risks in lending on FPSO projects has reached the stage that some lenders are now requiring vetting of the project management planned for the projects they lend on, an indication of the fragility of budgets and delivery schedules in the face of FPSO project overruns.

FPSO project performance

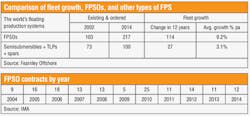

A more subtle hazard in the FPSO business is how it has grown. Some have even called it a "boom industry." Over the last 12 years, the world's fleet of FPSOs has more than doubled, showing an average growth rate three times that of the world's fleet of other floating production systems, including semisubmersibles, spars, and TLPs.

This growth has happened in fits and starts, with contracts for FPSOs varying substantially from one year to the next.

Securing these contracts and executing them during a boom and bust volatile environment such as that in 2008-2010 is certainly challenging in the face of shortages of experienced people and resources to get contracts done. No wonder things get off the rails sometimes.

Signs of hope

At an FPSO conference last September, a leading independent oil and gas company showed how its active intervention in the project management in two of its field developments in remote areas had resulted in bringing its FPSO projects in under budget, and early on schedule. Quite a contrast to these years of IPA statistics.

A panel discussion on project management at that FPSO conference heard from a veteran project director with a supermajor about its work in assessing its own actions and working toward improving the combined operator-contractor working relationship and processes. It was yet another sign of the FPSO industry attempting to get things better than they have been.

I happened to sit in on the preparatory meetings for that discussion panel: They were revealing, with a representative of one of the big three FPSO contractors talking about how they were striving to improve their project performance, being committed to performing in a professional manner whether he was in his employer's shoes or in the shoes of the operator.

At another FPSO conference last November, an official with a leading supermajor passionately stressed the values of insisting on installing extensive safety practices at the shipyard, and how that contributed to project performance.

These operator and contractor statements reveal a real willingness to be proactive in securing good project performance - a shift from years of the industry tacitly saddling the FPSO contractor with all responsibilities on project performance.

In a closely related industry, the shuttle tanker business faced challenges back in 2000, stemming from growth in fleet and growth in oil spills during North Sea operations that included serving many FPSOs. To counter this situation, a Norwegian-led initiative was created - DP 2000 - with operators, suppliers, and the largest shuttle tanker operator and pioneer Navion (now Teekay). Together, they addressed human factors, maritime operations and technology, and worked steadily on them over a three-year period. Incidents went down from 17 in 2000 to four in 2002: a truly remarkable management achievement. With that kind of combined industry success, perhaps there is hope for trimming back on the spills of money and time in constructing FPSOs.

When overruns happen

There are some basic reasons that some FPSO projects are going to overrun. A certain FPSO project in Angola over ran 12 months on schedule, all for very good reasons as the field development plan matured and changed with local requirements. Without knowing the real circumstances, it might sound as if that contractor's project team really blew it. But it was the right thing to do by both operator and contractor, and both were pleased with the outcome: an example ofdeliberate overruns.

Petroleum reservoirs are not the magical tanks of dollars the public might imagine. They are often very complicated assets that are difficult to understand, and that understanding improves as more wells are drilled and interpreted. So whether it was Angola or somewhere else, it is to be expected that changes may sometimes have to be made in an FPSO. That does not mean lousy project performance. One could wait until everything is exhaustively de-risked. But would that policy actually be workable with all the stakeholders (e.g. with a host country) desperate for revenues?

Hence, there needs to be a balance. An operator can wait until everything is as reliable and de-risked as far as it can reasonably achieve, or it can choose to proceed on the understanding the requirements for the field development may need adjustment as the project progresses. That may imply an overrun against initial budget, but adeliberate decision based on better information than at contract signing may well be worth it. That situation should hardly be "tarred" with the overrun brush.

An openness to change

If the real reasons why projects changed (and overran on cost and schedule) were known and properly attributed, then: (1) learnings may improve for future projects; and (2) the industry perception of poor FPSO project performance would recede. That is to say, poor perceptions of FPSO construction or project performance would diminish as it became recognized that there are sometimes good reasons for overruns, that are not due to lack of responsible management by contractor or owner.

A month before this article was completed, a vice president at one of the big three FPSO contractors confided that he was tired of his company being tarnished with the industry reputation of lousy project performance. It was an understandable reaction, bearing in mind the trouble his company takes to get it right, after years of hard experience and knowing it is their neck on the line if they get it wrong. It also was symptomatic of a pervasive lack of confidence in FPSO project management. Wider understanding of the risks faced and how they can be managed by responsible players may improve their dealings with financial institutions.

The time therefore does seem to be ripe for joint action to improve the perception of project performance. A simple learning would be the re-examination of what went on in a library of recently completed projects and acknowledging how much of the overruns were really contractor and really operator and why -deliberateandunintended, if you care to use that split.

Closing thoughts

In summary, here are a few closing thoughts on FPSO project performance. One can imagine the routine of a post-game show being applied at the end of each FPSO project, where project performance is discussed behind closed doors by operator and contractor, leading to sanitized numbers for public viewing that can be used to show real performance, often where shifts in scope and schedule are made for sound business reasons. This would introduce the concept ofdeliberate and unintended overruns. This may not represent the ultimate codification of what goes on, but it would be a start.

The goal is to build industry confidence that FPSO projects can become fairly predictable with careful management. It may lead to an upfront recognition that the budget is indeed subject to ±X and even a range of ±Y months on delivery. This would offer another side to the years of IPA statistics that have led to simplistic often negative signals on project performance with FPSOs.

We may now encourage financial institutions to see and work with the risks that do exist. Practically, lenders and the industry may become more conscious that there are managed processes in place within the FPSO contractors for what can be a fundamentally difficult risky business.

Twenty years ago, drillship construction often ran over like FPSOs do today, sometimes leading to mergers and acquisitions. But that is no longer the case. Their project performance has become quite predictable. However, drillships are not field specific like FPSOs, meaning that the scope and project definitions can be more readily settled in advance and they become a more fungible investment. We may never reach that standard of predictability and uniformity for FPSOs, since they tend to be more different, one to the next. So why not recognize this, rather than continue the impression that these associated with FPSO projects allow them to get out of control all too easily?

It is in the best interests of contractors and operators to improve project performance. The timing is good now for such a dialogue, as recent comments from both operators and the big three FPSO contractors have indicated.

Is it conceivable that the FPSO industry might one day follow the drillers and have its own trade association, the International Association of FPSO Contractors (IAFC), its equivalent of the IADC? That organization has provided decades of thought and advice that has been vital in developing standard contracts and daily reports. The MODU owners have been at it longer with roughly three times as many units as the FPSO owners. Maybe we in the FPSO world can learn a thing or two from them. •

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to thank the big three FPSO contractors (BW Offshore, Modec and SBM) for their comments, reality checks, and encouragement from their review of this article.

The author

Peter Lovie's 48 years of experience in engineering and management in the offshore industry have all been in Houston, initially on offshore drilling-related business. Over the last 20 years, Lovie has become known as something of an industry authority on FPSOs, from his unusual combination of working on both the contractor and operator sides of the FPSO business as well as the necessary shuttle tanker side of it (Bluewater, American Shuttle Tankers, Devon Energy). He is known for his contributions leading to the first FPSO and shuttle tankers to enter service in the Gulf of Mexico. He has been a frequent speaker and moderator at FPSO conferences worldwide, and during 2012-2014 served as Program Chair for the FPSO conferences in September cited above.

Lovie started in the oilfield with Cameron and The Offshore Company (now Transocean), then founded an engineering company (ETA) with its introduction of a new generation of jackup drilling rigs in the 1970s, built in France, Singapore, and Japan. That was followed by marketing and contracting MODU construction, then a stint in subsea processing.

Lovie is author of five US patents, numerous technical papers, and conference presentations. His credentials include: Professional Engineer in Texas (PE), Project Management Professional (PMP), and Fellow of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects (FRINA). He earned his Master of Applied Mechanics degree at the University of Virginia where he was a Fulbright Scholar, and his B.Sc. in Civil Engineering from University of Glasgow in Scotland.