Early efforts in Cook Inlet foreshadowed later Arctic challenges

Joseph A. Pratt

University of Houston

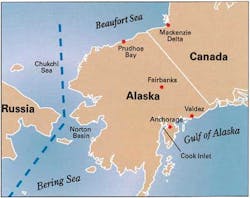

The Cook Inlet is not "offshore" in the open waters of the ocean; nor is it above the Arctic Circle, which is some 500 mi (805 km) to the north. But operations there in the 1960s foreshadowed the difficulties the industry would face in the 1980s as it searched for oil offshore in Arctic waters, where it found lower temperatures, higher winds, and thicker ice than in the Cook Inlet. In the brief boom offshore northern Alaska and Canada in the 1980s, oil companies also found that they could not yet operate profitably in the Arctic. Their experience is of interest today as many of the same companies contemplate offshore work in much wider arctic areas.

Now, as in earlier Arctic ventures, ice remains the key barrier to success. The Cook Inlet was a particularly hard teacher on the subject of ice. Ice floes there move back and forth with tidal variations as high as 30-35 ft (9-10.5 m). Early studies concluded that lateral wind, current, and ice forces on a typical four-legged, self-contained platform in the Cook Inlet were three to four times as great as wind and wave forces on platforms in the Gulf of Mexico.

The new Cook Inlet platforms had to withstand twice the thrust of the Saturn V rocket used in the Apollo moon shots. They cost several times more than traditional Gulf of Mexico platforms, and their weight tested the limits of existing barges used to transport and install jackets. Considering high costs, the challenge of extreme ice movement, the distance from established equipment and supply companies, and the severe cold and harsh winds in the Cook Inlet, it is not surprising that in the 1960s,Offshore concluded that operating conditions there were "worse than any spot on the globe."

Jacket designers attacked the ice floes with two major weapons: very conservative design loading that far exceeded real forces measured on the jackets and new designs to deflect ice. One innovation was the "large-legged" jacket with four legs up to 28 ft (8.5 m) in diameter built from low-temperature steel with no diagonal supports in areas subject to ice forces. These were quite heavy jackets for shallow water, but they stood up to the extreme ice movements in the Cook Inlet.

Another innovate design was the "monopod," a one-of-a-kind 130-ft (39.5-m) tall structure that stood on a single leg about 28.5 ft in diameter. Built for a 60-ft (18-m) water depth with an additional 30 ft to account for tidal variations, the monopod rested on large pontoons that spread the forces exerted by ice. This unique and strange-looking structure sparked great interest in the industry. Although it performed acceptably in depths up to 100 ft (30.5 m) in a harsh, ice-filled environment, it received mixed reviews. Its design lowered costs; one leg used significantly less steel than four smaller legs. But those who worked on the monopod recalled that it was not "real comfortable," and it did not pass the "toilet test." Large chunks of ice that came to rest against the leg and the pontoons jerked the platform as they broke free, giving a "good splash" to those sitting on the toilet. One engineer involved in the project concluded: "It has managed to survive, so I guess it wasn't too bad." In the absence of experience with heavy ice floes and of the powerful computers that came later, that was the best result that could be expected.

Too heavy to be transported on existing barges, these jackets were self-floating structures built in fabrication yards in Washington state and Texas and floated to the Cook Inlet, where the flooding of two of the four large-diameter legs eased them to the bottom. In some cases specially fabricated, detachable flotation devices helped reduce the exposure to ice of the permanent structure during installation. If something went wrong, however, help was far away in repair yards in the lower 48.

This became abundantly clear during the installation of a large Mobil Oil platform by Brown & Root. When the detachable flotation tank released prematurely, the jacket broke loose from cables that held it to the derrick barge and was carried away by strong currents. It moved up and down the inlet for a week as Brown & Root scoured the western US for barges large enough to regain control of the partially flooded structure.

To help corral it, the company placed an employee onboard. As he rode up and down the inlet, he kept an air compressor going and checked the pressure in the legs. "It was a lonely job," he recalled, "because you could have fallen off in that cold, swift water up there." Local newspaper accounts reported the ordeal with cartoons depicting Texas cowboys trying to rope the jacket. Company engineers could only point to an underlying truth: "People tended to underestimate the dangers of these new areas because everything was extrapolated from such a nice calm place as the Gulf of Mexico." Although the industry did find and produce commercial amounts of oil from the Cook Inlet, its early encounter with severe ice foretold difficulties to come.

As development there went forward, several companies studied conditions above the Arctic Circle in the Canadian sector of the Beaufort Sea. Interviews of those involved tell the story of the early struggles to understand the demands of E & P in the Arctic at a time when commercial production from the region remained a distant dream.

Conditions were extraordinarily demanding, even in comparison with those in the Cook Inlet and the North Sea. Knowledge of ice was scarce, and hazards from moving ice remained "the controlling factor in all Beaufort Sea operations." Extreme cold for much of the year meant that Arctic ice posed more complex problems than the ice floes in the Cook Inlet. Researchers classified different types of ice found as operations moved northward and as the weather changed during the year. They made progress in understanding the forces exerted by ice in various situations.

Although many acknowledged the potential of the region, few willing players were ready to accept the risks and costs of exploring for oil in this imposing climate.

Displaying 1/3 Page 1,2, 3Next>

View Article as Single page