Risk factors include age, deck height, water depth

Mark J. Kaiser • Siddhartha Narra

Center for Energy Studies, Louisiana State University

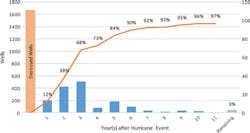

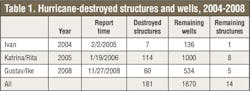

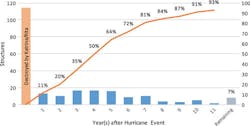

From 2004-2008, five major hurricanes (Ivan, Katrina, Rita, Gustav, and Ike) destroyed 181 structures and 1,670 wells in the Gulf of Mexico. Through 2016, 167 of the destroyed structures have been decommissioned, and almost all of the associated wellbores have been permanently abandoned. The decommissioning sector’s ability and success in dealing with unprecedented levels of destruction is a notable accomplishment for the industry.

With only a few structures remaining to be decommissioned, there are some data peculiarities which leave interpretation ambiguous in some cases. This ambiguity arises from production (apparently) associated with the destroyed structures, probably due to one or more “bad well links” as discussed below.

Decommissioning activity

The number of destroyed structures from the five major hurricanes is from official government press releases based on operator data provided approximately two-to-three months after each hurricane.

Destroyed structures are either toppled to the seafloor, leaning, or physically damaged beyond repair. However, structures that were significantly damaged and where operators later decided to perform early decommissioning are not included in the counts.

All the destroyed wells and structures from Hurricane Ivan have been decommissioned except Taylor Energy’s Mississippi Canyon 20 structure and 19 remaining wells. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita destroyed 114 structures and 1,000 wellbores; five structures remain circa May 2017. Hurricanes Gustav/Ike destroyed 60 structures and 534 wells; six structures remain circa May 2017.

Remaining activity

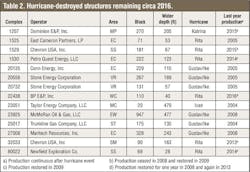

Hurricane-destroyed structures and wells remaining to be decommissioned are shown by operator in Table 2.

Four of the destroyed structures in 2005 exhibit production continuous through the hurricanes, indicating that the well links associated with these structures are probably bad (erroneous), or the platform may have been associated with a complex and not properly identified. These structures include: 1207, 1525, 32033, and 80022. If the well links are not bad, then the destroyed structures were not properly identified.

One structure destroyed by Rita in 2005 (1529) indicated production cessation in 2008, which was subsequently restored in 2009, indicating possible misidentification by event.

One structure (1530) restored production after its destruction but is not currently producing.

One structure (22438) restored production after Rita blew through, but appears to have been damaged by Gustav/Ike since production ceased in 2009, production was restored again in 2012 and is currently producing.

Two structures destroyed in 2005 (1530 and 22438) recovered after the event, meaning that production ceased, clean-up occurred, and a new structure installed or production from the wells was re-routed to another structure, but a new link was not established.

Well link reliability

Producing wells in the GoM are linked to the first platform the well boards for processing, but the question arises, how reliable are the well links? Are producing wells linked to the platform indicated by the link code? This is a difficult question to answer because there is no direct way of identifying potentially mislabeled wells and if they are boarding the “right” platform.

However, hurricane events appear to reveal their presence. A small number of hurricane-destroyed structures show production immediately after being “destroyed” and for months and years thereafter, which is clearly an impossibility for a destroyed structure, indicating that the well was not physically associated with the structure in the first place, or the structure was improperly identified as destroyed. These possible causes seem to be equally likely.

If the well link was “bad,” then when the structure was destroyed and all its “real” wells ceased production, the improperly linked wells continued to produce and report production since they were actually associated with another platform that was not destroyed.

If the well links on hurricane-destroyed platforms are representative of the GoM, the authors guestimate that well links may not be properly classified in at most 1% to 2% of GoM wells, which for all practical purposes is negligible and should not be a cause for concern since it is part of the background noise inherent in all large dynamic databases.

Risk factors

For the past several years, almost a decade now, the GoM has been spared major impact from storms, but the risk of hurricanes is ever-present.

The size of the storm is important, but the track it takes, forward speed, and duration are also key factors in determining its impact. For example, Hurricane Ike was just a Category 2 hurricane, but it caused significant damage because its hurricane force winds extended out 400+ nautical miles and its track took it over a populated area of infrastructure. The distance the wind blows over a body of water and the duration of the high winds, the higher the waves can become.

Age, deck height, and water depth are three primary risk factors for structure damage/destruction in a hurricane. Deck height is probably the most important factor, since if waves hit the deck, there is a strong likelihood it will sustain significant damage and be toppled. Age is important because design requirements have changed over time, resulting in greater air gaps since 1970. Deck height depends on subsidence and platform function and the design standards employed at the time of installation.

Platform orientation relative to the hurricane wave direction can play a role in damage in some cases, and well conductor density, if high, presents a greater surface area exposed to waves which may also play a role in destruction.

Using GoM destroyed structures from 2004-2008, statistical risk factors based on age and water depth were computed by counting the number of destroyed structures in each hurricane relative to the number of surviving exposed structures at the time of the event (based on data from Gary Siems, Decommissioning Manager at Stone Energy).

Structures installed before 1970 were five times more likely to be destroyed than structures installed in the 2000s (10.3% vs. 1.6% destruction rate) and three times as likely as structures installed in the 1990s (10.3% vs. 3.4% destruction rate).

Structures in the water depth range 100-400 ft were two times more likely to be destroyed than structures in deeper water (9.7% vs 4.8% destruction rate), and five times more likely than in shallower water (9.7% vs 2.1% destruction rate).

Future hurricanes will have their own distinct paths, speeds, central pressure and strength, and will enter the GoM with a different density and distribution of structures than last decade, but if “similar” hurricanes were to enter the oil patch, one might expect a “similar” destruction rate among “similar” structures. The age distribution of structures in the GoM is not remarkably different than they were a decade ago, but fewer structures populate the region, about 2,300 structures circa 2016 but the risk factors are likely to be approximately constant.