Market downturn presents opportunity for fundamental change

Industry leaders working toward sustainable solutions

Mike Dyson

Navigant

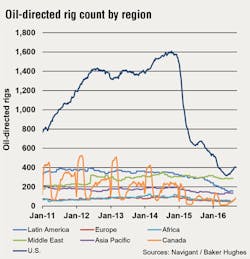

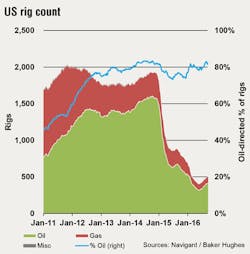

Upstream oil and gas continues to face its biggest challenges in a generation. Oil and gas prices are off the bottom but remain low at approximately $50/bbl and $2.75/MMBtu. The market fundamentals - oversupply, reduced demand growth, and in the case of crude, large inventories - remain resilient. This imbalance will eventually work itself out, but the expectations regarding timing and profile of price recovery vary.

Market trends

Industry veterans recall previous price slumps - notably 1986, 1998, and, to a lesser extent, 2008. There are differences this time, including the effect of supply-side excess and the role of shale oil, which are leading to much slower price recovery. Previous recoveries were V-shaped, but this one is more L-shaped.

Most oil and gas companies are planning on a “lower for longer” price environment, and some are carrying “lower forever” downside scenarios. In the short term, crude inventory will need to be depleted. Once recovery starts, shale oil producers will enter the market again, adding crude and dampening further price recovery. Unless there are major disruptions in supply or a change in the OPEC strategy, price recovery will be extended.

Over the last 18 months, companies in the sector have been under tremendous cash flow pressure. Even when crude was over $100/bbl, returns on development project investment deteriorated from 20% to less than 10% in many cases. The industry passively accepted high costs and deep-rooted inefficiencies. There was an oilfield premium on everything.

In some offshore provinces such as the UK North Sea, the situation is compounded by depleted fields and aging infrastructure. It is possible that less than 50% of such fields are net cash positive at $50/bbl oil. Cessation of production and the likely abandonment of platforms and wells looms large. However, the incentive to remain operational during the downturn is powerful: once closed down, a platform will not restart. How have firms responded to this situation?

First responses

Initially the industry cut approximately half a trillion dollars of investment in new projects. Other actions largely focused on addressing over capacity, reducing the workforce, and cutting general and administrative costs. Lower activity levels have already translated into lower costs. There has also been consolidation in the industry (e.g., Shell acquiring BG Group), though less than in previous downturns. Halliburton’s failure to consolidate its offer for Baker Hughes may be an indication that this can only go so far. Nonetheless, there is capital ready to be placed into upstream merger and acquisition activity at both the company and individual asset level, once values become clearer.

The following sections summarize how the industry moved beyond these initial responses and is now responding to the market’s challenges.

Joint ventures and alliances

Traditionally the oil and gas industry leveraged joint ventures and alliances with operators and government partners to share costs and manage overall venture risks. But, within the supply chain of goods and services - during both the project and operating phases - these alliances have been much less common than in other industries. Take drilling contracts in which the contractor is usually employed with a day rate contract, for example. There is little incentive to invest in efficiency improvements, and short contract durations result in significant change costs for the oil and gas industry. These traditional contractual boundaries, as well as risk allocation and contract arrangements, have enabled inefficiencies that market players can no longer afford. Longer-term agreements and shared risk/reward contracts with key suppliers offer the opportunity to reverse this situation. Operators are reluctant to relinquish control to the extent needed, but they are starting to do so. Acceptance that the industry will either succeed together or fail together is pervasive.

Although operators are competing in some areas (licensing, exploring, understanding the subsurface, and attracting talent), there is little differentiation between players in many areas. Therefore, cooperation is a more effective strategy in a low-price world. This thinking has driven the formation of focused industry task forces across operators, suppliers, and government parties in the last 18 months.

Supply chain and logistics

Industry interface costs used to be significant because of ineffective sharing and ownership of data, poor cost-driver transparency, lack of close collaborative working, and contracts that did not encourage business improvements or use of new technology. Shared logistics, leveraged by optimization and tracking technologies, applied to supplier inventory, storage yards, supply boats, helicopters, and offshore hoteling are areas where collaboration between operators can reduce costs while still maintaining flexibility. In an interesting application, optimizing passenger seat assignment in an aircraft reduced helicopter costs. In particular, cost transparency - both purchase costs and costs arising from customer demand/specification - is proving essential to understanding the opportunities to be challenged in the supply chain.

Standardization

Although industry standards exist, many operators have traditionally defined their own. Even within operators’ activities, there can be a bewildering and costly variety of designs. In recent years, the industry has gold-plated some equipment in an effort to optimize the technical design - often at the expense of greater manufacturing and servicing costs. Although late to this effort, there is now an increased belief that the industry needs to go back to the basics, implementing minimalist - zero-based - and functional design requirements. In areas such as contract, training, personnel qualification, and data standards, benefits can be immediately delivered, and industry bodies are heavily promoting this effort. Process standardization is a key component of performance improvement, and the subject of many Lean and Six Sigma performance improvement programs.

Technology

Upstream oil and gas has historically leveraged technology to find and produce hydrocarbons from deeper, further, and tighter formations downhole. Now there is a focus on using technology to cut costs instead-something much more akin to other industries. A recent article identified that GE and Shell are seeing a shift from operations as an art to operations as a science. Traditionally teams working in production operations or drilling offshore largely worked independently from those providing onshore-based support. Reliable low-cost, high-bandwidth communications now enable much greater transparency of performance data and metrics and the use of collaborative tools, both formal and informal. The industry already collects masses of data, but now big data techniques offer the ability to add value to operational decisions. Wider application of the Internet of Things, even retrofitted to brownfield operations, also offers the opportunity to directly support decision-making with real-time quality information.

Data visualization and transparency is one area that can transform staff awareness and allow chronic problems to be elevated and solved.

Other applications of new technology abound. For example, operators are carrying out routine inspections using robotics and drones to reduce costs and, in many cases, increase safety. Those with experience of downstream oil and gas operations, which has a long history of cost and efficiency focus, are pressing for much wider use of process optimization techniques in the upstream sector to maximize reliability and overall costs.

Workforce efficiency

Oil and gas companies, as well as many of their contractors and suppliers, tend to be organizationally siloed and rarely physically co-located, placing emphasis on asset first or function first. This needs to change, and this change is beginning to take place through greater collaboration within and outside the corporation.

Locating people offshore is expensive, and there is renewed emphasis on spanner time, the proportion of time an offshore technician is actually engaged in the practical aspects of the job. This has increased over the last couple of years, in some cases three-fold. Another drive is toward multi-skilling - providing offshore workers the skills and capability to cover activities done previously by others. Another example involves using tracking technology to benchmark individual drilling operations and drive out inefficiencies.

Turnaround planning

Long a weakness in the offshore sector, turnaround/shutdown planning and execution have had significant negative impacts on overall production efficiency. Overrun schedules and costs have been the norm. More rigor and better planning tools have significantly improved performance in this area: in 2015, UK North Sea oil production increased for the first time since 1999.

Learning from others

Offshore operators can learn significant lessons from the North American onshore shale oil and gas business, including the relentless approach to cost efficiency, flexibility, standardization, collaboration, technology, and the public benchmarking of performance. Above all, the need is to recognize how to learn and implement quickly.

Leadership

How are industry leaders dealing with all this? It varies. A few appear to remain in denial, while others anticipated the low price challenges as early as 2013. Some are demonstrating genuine management courage - stepping up and leading the charge for needed changes and championing solutions outside the boundaries of their own organizations to demonstrate to the broader industry what is possible. The best are making changes beyond just the cosmetic; they have an eye on sustainable solutions rather than short-term fixes, and are driving the associated cultural transformation that needs to accompany and support change. Many organizations understand the value of this approach even if prices recover faster than expected, and all realize that sustaining the gains will be a challenge.

The author

Mike Dyson leads Navigant’s upstream oil and gas consulting business outside North America, an expanding area of business for the company. He brings more than 30 years’ experience in the upstream oil and gas business, having worked in major and large independent exploration and production companies around the world. His core expertise is in well and production operations, capital projects, supply chain strategies and new technology development and implementation. Dyson focuses on advising oil and gas E&P companies that are seeking to improve their business performance. As a leading expert, he delivers the Well Engineering component of the Petroleum Engineering MSc course at Imperial College, London, UK.