Kenneth B. Medlock III

Rice University

A number of factors have converged to contribute to the increase in oil prices since 2000. Indeed, strong demand growth in Asia, resource nationalization that limits access of international capital to low cost resources, slow to no growth in non-OPEC supplies, and a dramatic increase in drilling and completion costs have all contributed. According to research at the Baker Institute's Center for Energy Studies, US fiscal and monetary policy have also resulted in substantial devaluation of the US dollar relative to other major currencies since 2000 and contributed to a rise in dollar-denominated price of oil, and other internationally fungible commodities. There is also concern that the increased flow of capital into financially traded commodity markets, evidenced by a substantial increase in open interest for commodity derivatives, has contributed. Regardless, the current price environment facilitates considerable interest in exploring new frontiers in hopes that new production targets can be identified.

In the US, high prices have stimulated a wave of activity that has been nothing short of transformative. Over the last several years, US oil production has surged, reversing decades of decline. This has been driven primarily by the development of light tight oil (LTO) resources in shale plays. LTO resources are distributed widely across the US, with development already occurring in North Dakota (Bakken) and South Texas (Eagle Ford), and beginning to emerge in places such as West Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Kansas. There is even oil and liquids production potential in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Colorado, and California. Activity in the Bakken and Eagle Ford shales currently account for most US LTO production. While not all shales are created equal, if production growth occurs in the emerging plays in any semblance of what we have seen in the Bakken and Eagle Ford, the US could be awash in oil in the coming decade. Indeed, the International Energy Agency recently projected that the US would rival Saudi Arabia as the world's largest oil producer by 2020.

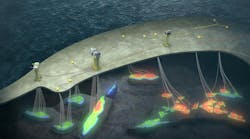

While onshore production from shale formations has dominated recent growth, it is not the only area under active development. There is considerable interest in expanding production in theUS Gulf of Mexico (GoM), and although GoM production has flattened recently, growth prospects remain strong over the next several years. Shallow-water GoM is a mature province, but will remain a viable target of opportunity for firms seeking to enhance recovery from older fields. Deepwater GoM, on the other hand, is among the most attractive offshore opportunities for large upstream capital investments in the world. Despite strong interest in Brazil and West Africa, the US is seeing higher levels of investment by a more diverse group of developers. Indeed, deepwater is poised to drive an overall increase in offshore US production, after years of steady decline.

Overall production growth since 2008 is accelerating a downward trend in imports in the US, but demand is also playing a key role. Recent demand trends are reflective of the impacts of higher oil prices and a weak economy, but these trends may also signal longer-term demand destruction. If US demand growth remains soft due to improved end-use efficiency and consumer conservation, then continued growth in US production will stress the existing paradigm. In fact, the debate in Washington regarding LNG exports over the last 18 months has been a prelude to a much larger debate regarding crude oil exports. "Energy security" is usually at the center of these discussions, but such concerns are not beyond reproach. For instance, it can be argued that not allowing exports imposes an economic cost that outweighs any benefit of the current policy. Specifically, these arguments include the following:

- Banning exports imposes capital requirements on refiners that are not otherwise present.

- Banning exports can result in domestic crude oil prices being discounted to international crude oil prices. Importantly, gasoline prices at the pump will not move with a discounted domestic crude oil price because petroleum products are internationally fungible. So, while refiners may see better margins, consumers see no benefit. Moreover, if domestic prices are suppressed through a policy-constraint, upstream activity will be challenged.

- Not allowing exports ignores the fact that exports of LTO would effectively be a swap that improves the trade balance, whereby US producers could export higher priced light crude while importing lower priced heavy crude for refining.

Regardless of one's position on the question of oil exports, the outcome of the debate will significantly impact activity in the offshore GoM (and onshore for that matter), and should be weighed heavily.

Aside from the pending issue of oil exports, another significant wild card is the prospect of energy reform in Mexico. Should reform be successful in attracting foreign capital, a wave of entirely new exploration targets could be opened, which could, in turn, trigger substantial opportunities for large international oil and gas firms as well as service providers along the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast. Thus, the US-based service industry could see its demands grow in the next several years beyond what many think possible.

There is also substantial onshore shale resource development opportunity in Mexico, which is smaller in scale and could attract both small and large operators from across the border in the Eagle Ford shale in South Texas. However, safety of personnel is a major concern. This salient point makes it highly likely that offshore development opportunities will progress more readily, at least until the safety issues related to cartel activity in northern Mexico can be addressed. It is important to note that the exact terms of energy reform are still unclear, and Mexico must offer attractive terms to attract much needed foreign capital. Absent this, reform will not be successful in triggering oil and gas activity in Mexico - onshore or offshore.

Finally, the most prescient determining factor in evaluating the future of oil production in the US - both onshore and offshore - is price. So, one must ask if oil price will remain strong enough to support continued movement into more costly frontiers. Of course, there are things that could cause price to fall suddenly - for example, if Asian economies suddenly slow, or harmonious relations emerge in the Middle East - but that simply means the oil and gas industry must remain flexible and be as resilient as ever.