Martin Wareham

Forum Energy Technologies

Today's industry standard work-class ROV can be designed to accomplish underwater almost any task that can be performed at the ocean's surface while allowing the vehicle operator to remain secure while the ROV works below.

Over the last 30 years or so, ROVs have increased in reliability and capability to the point where they are now the only way of carrying out certain underwater operations, particularly in very deepwater for example. Heretofore, ROVs were simply been considered diver replacements.

ROVs are generally the tool of choice for site and route surveys to help determine the best installation routes for pipelines and cables. While observation ROVs are normally used as a visual aid in shallow water, work-class ROV systems are used in deeper water, areas of high current (2 to 3 knots), and when intervention tasks require the use of manipulators, fluid transfer, or payload bearing capabilities. The work-class ROV is the most common intervention tool for call-out work because operators have the capability to mobilize quickly and be ready to work once on site. Generally, these call-outs last for a few days, although they may be extended to several weeks. Once work is complete, the system usually demobilizes immediately.

There is a very wide range of ROV types built by a number of ROV manufacturers. These vehicles can carry out a large number of different underwater tasks. This makes for a very competitive marketplace.

As the ROV industry progresses, the major manufacturing and operating companies are committed to produce more user-friendly and easier to maintain work-class ROVs that can provide more horsepower at greater water depths.

Smaller ROVs are now doing the work that would have been the domain of much larger ROVs in the past, while larger ROVs are pushing the envelope of what was thought impossible for them to achieve in the past.

Significant ongoing ROV developments include the following:

- ROV sensor manufacturers are providing ever more capable sensing products. This will continue to push the boundaries of what an ROV can do underwater.

- Smaller ROVs will continue to become more capable and effective at tasks that previously required much larger ROVs. This is due mainly to technology advancements in materials, power transmission, control systems, data transmission rates, and sensors.

- ROVs will become more capable of diagnosing their own faults as their overall system complexity increases faster than the finite number of experienced ROV pilots.

- ROVs will carry out more and more autonomous and semi-autonomous tasks underwater. This will obviate the requirements for very skilled operators who are becoming fewer and farther between. Larger ROVs will continue to perform more "power hungry" underwater tasks.

- Integration of ROVs into subsea infrastructure will play more of a part in the future of ROVs.

- Universities will continue to increase their understanding of underwater environments, especially with regards to metocean change with the help of ROVs.

- Subsea and offshore renewable power generation will rely more and more heavily on the ROV of the future.

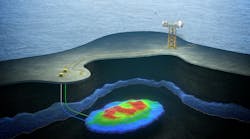

- The ROV of the future will further enhance the safety and continued successful operation of subsea oil and gas exploration and production.

- Teaching people about underwater flora and fauna will be carried out more effectively by ROVs in the future.

The future demand and development of ROVs will grow with the rise in offshore exploration and subsea field development. Strong growth in demand for ROV support of offshore operations is anticipated through 2015.

Oil and gas ROV market to reach $2.5 billion in 2013

As expenditure in deepwater areas and on subsea infrastructure around the world increases, ROVs will become an increasingly critical aspect of offshore oil and gas development. The positive growth forecast for the development of the deepwater market and subsea infrastructure market, along with the increased focus on safety and security, mean that ROVs will take on an even more important role in the oil and gas business. As a consequence, Visiongain has determined that the value of the market for ROVs in the oil & gas industry in 2013 will reach $2.458 billion.

The depth records for AUVs continue to increase, too. An AUV is an autonomous underwater vehicle and has no direct connection to a surface vessel. A cooperative venture of the University of Southern Mississippi and the University of Mississippi saw theEagle Ray AUV operated by the National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology complete a Gulf of Mexico survey that reached depths of 1,634 m (5,360 ft). The Explorer-class AUB is rated by USM for operations to 2,200 m (7,216 ft).

At about the same time, a Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution AUV named Mola Mola completed a mission at a depth of 1,612 m (5,287 ft).

There are several categories of ROVs organized as follows:

- Micro - Less than 3 kg and used where a diver cannot enter

- Mini - Around 15 kg and also used as an alternate to a diver

- General - Less than 5 hp and often carrying small manipulator grippers and perhaps a sonar unit

- Light work-class - Less than 50 hp and capable of carrying manipulators

- Heavy work-class - Less than 220 hp and carrying two manipulators

- Trenching/Burial - More than 220 hp but less than 500 hp and can carry a cable laying sled.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com