EU develops regulatory response to Macondo oil spill

Vlad Popovici

ShawCor

No one doubted that theDeepwater Horizon accident would lead to significant and lasting changes in how offshore oil and gas facilities are managed around the world. As a result of an assessment process started in 2010, the European Commission has unveiled a proposal for a new regulation on the safety of offshore oil and gas prospection, exploration, and production activities.

Although such an initiative might be justified, it could open a new legislative front for the European Union in a sector where it has relatively limited regulatory expertise. Early signals from the offshore oil and gas industry to the proposed regulation vary from reservation to outright opposition, since it could create significant additional compliance costs for EU offshore operators. Furthermore, the proposed regulation cannot be enacted in the proposed structure without the development of further complementary legislation.

In May 2010, the European Commission started a gap analysis aimed at reviewing the applicable European offshore legislation in order to identify the main areas where action is needed to significantly reduce the safety and environmental risks linked to offshore exploration and production. These areas in need of further action were presented by the European Commission to the European Parliament in July 2010: thorough licensing procedures; improved controls by public authorities; gaps in applicable legislation; reinforced EU disaster response; and international cooperation to promote offshore safety and response capabilities worldwide.

In response to the Commission's assessment, in September 2010 the European Parliament adopted a resolution that called on the Commission to develop a comprehensive legal framework to ensure uniformly high safety standards, accident prevention preparedness, as well as disaster response and liability rules across the EU. As a result, the European Commission published a communication in October 2010 that initiated a public consultation for the preparation of new legislation which would cover the topics proposed by the Commission assessment and the European Parliament's requests. Finally, after one year of legislative development, in October 2011 the European Commission published the "Proposal for a Regulation on safety of offshore oil and gas prospection, exploration and production activities," with impact assessments.

Proposed legislation

The main risk drivers that had to be addressed by the new EU legislation are identified in the impact assessment documents that accompany the Regulation proposal. According to the European Commission press release that announced the proposed regulation, an event on the scale of theDeepwater Horizon accident could cause damages of €30 billion ($39 billion) in Europe.

Taking into account these risk drivers, the proposed regulation has two general objectives: to reduce the risks of a major accident in the EU waters, and to limit the consequences should such an accident nonetheless occur. Furthermore, the two general objectives are developed in four specific ones:

- Ensure a consistent use of best practices for major hazards control by oil and gas industry offshore operations potentially affecting EU waters or shores

- Implement best regulatory practices in all European jurisdictions with offshore oil and gas activities

- Strengthen the EU's preparedness and response capacity to deal with emergencies potentially affecting EU citizens, economy, or environment

- Improve and clarify existing EU liability and compensation provisions.

The Commission assessed several policy options to address these risk drivers. These options have been evaluated using a cost/benefit analysis by quantifying the risk reduction versus the compliance costs created for the member states, the industry, and the EU, taking into account the wider non-quantifiable (social, economic, and environmental) impacts. The Commission finally selected an option that entails a set of new rules that should cover the whole lifecycle of offshore exploration and production activities from design to the final removal on an oil and gas installation:

Licensing. The licensing authorities in member states will have to make sure that only operators with technical and financial capacities sufficient to control the safety of offshore activities and environmental protection are allowed to explore for and produce oil and gas in EU waters.

Independent verifiers. The technical solutions presented by the offshore operators that are critical for safety of their installations need to be verified by an independent third party prior to and periodically after the installations start operating.

Emergency planning. Offshore operators must prepare and submit to member state authorities major hazard reports for their installations, including risk assessments and emergency response plans before exploration or production begins

Inspections. Independent national competent authorities responsible for the safety of installations will verify the provisions for safety, environmental protection and emergency preparedness of rigs and platforms, and the operations conducted on them. If an operator does not respect the minimum standards, the competent authority will take enforcement action and/or impose penalties; ultimately, the operator will have to stop drilling or production operations upon failure to comply.

Transparency. Comparable information will be made available to citizens about the standards of performance of the industry and the activities of the national competent authorities.

Emergency response. Offshore operators will prepare emergency response plans based on their rig or platform risk assessments and keep resources at hand to be able to put them into operation when necessary. Member states will compile national emergency plans. The plans will be periodically tested by the industry and national authorities.

Liability. Oil and gas companies will be fully liable for environmental damages caused to the protected marine species and natural habitat.

International. The Commission will work with its international partners to promote the implementation of highest safety standards across the world.

The proposed regulation also requires the creation of a new institution, the EU Offshore Authorities Group, which will group all the competent authorities from the member states. The group will share offshore best practices and contribute to development and improval of safety standards.

Finally, in conjunction with the proposed regulation, the Commission is proposing the EU accedes to the Protocol of the Barcelona Convention that protects the Mediterranean against pollution from offshore exploration and exploitation activities.

In terms of coverage, the proposed regulation would apply to all activities related to exploration, production, or processing of oil and gas offshore, including the transport of oil and gas through offshore infrastructure (pipelines) to another offshore installation, onshore processing or storage facility, or for transporting and loading oil to a shuttle tanker. The new regulation should apply not only to future installations and operations but also to existing offshore installations (subject to transitional arrangements).

For damage to waters, the regulation would cover all EU marine waters including the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) – up to about 370 km (230 mi) from the coast, extended from the present EU legal framework for environmental liability that is restricted to territorial waters (about 22 km, almost 14 mi, offshore), and the continental shelf where the coastal member states exercise jurisdiction. From the geographical point of view, the regulation would be applied in all the EU marine waters as identified by Art. 4 of Directive 2008/56, namely the Baltic Sea, the Northeast Atlantic Ocean (with the Greater North Sea, including the Danish Straits and the English Channel; the Celtic Sea; the Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Coast; the waters surrounding the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands), Mediterranean Sea, and the Black Sea. Although the regulation would be applicable to all companies with offshore operations in EU waters, the EU-based companies are expected to commit to the same standards when working outside the Union. Finally, it is stated that the proposed regulation has potential relevance not only for the EU countries, but also for the European Economic Area (EEA) members – EEA is EU+Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein – and the Energy Community countries, namely the western Balkans countries, Turkey, and Ukraine.

European energy conundrum

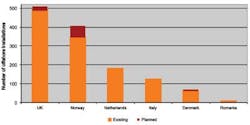

The willingness of the EU to get involved in regulating the offshore oil and gas sector seems justified. According to the above-mentioned October 2010 Communication of the EU Commission, more than 90% of the oil and more than 60% of the gas produced in the European Economic Area (EEA) is coming from offshore operations, mostly in the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea. Most of the EEA offshore installations are in Norway, UK, Denmark, and the Netherlands, while smaller scale offshore activities take place in Italy (in the Mediterranean) and Romania (in the Black Sea). Significant offshore operations also take place in adjacent non-EU regions, such as offshore Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. Moreover, in the future more offshore production facilities will be installed in the North Sea, while exploration is already ongoing or is expected to take place soon in offshore regions that did not traditionally have such activities, such as the Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean.

In the immediate aftermath of theDeepwater Horizon, there were calls for extreme measures, including a ban on all new deepwater drilling activity. Fortunately, the European Commission seems to have chosen a pragmatic approach. Against the background of higher exploration and production risks in increasingly deeper waters, the underlying long-term EU objective of improving its security of energy supply encourages the increase of the domestic hydrocarbon production. This is the conundrum that the proposed regulation trys to address – continuing to develop critical European offshore oil and gas resources, while improving the sector's regulation. In this context, we note several positive aspects of the regulation proposal. These are:

Transparency and reporting. The regulation proposes the creation and use of a common data reporting format for major incidents, and emergency and response plans across all member states (Art. 23 and Annex VI). This would allow the sharing of comparable data between the EU countries, as well as the development of an EU-wide database to assist in disseminating the lessons learned from major accidents and near misses. The EU countries would also be required to prepare an annual report concerning the impact of their offshore operations – numbers, age and location of offshore installations, inspection activity, incident data, etc. – while the Commission would consolidate every two years an EU-wide offshore impact report, based on the national reports (Art. 24). These requirements would definitely add value to the industry and support an improvement of the offshore safety.

Avoiding conflict of interests. Following the lead of the US federal regulatory reform that divided the former Minerals Management Service (MMS) into two parts, the regulation draft requires in Art. 19, paragraph 1 that "The competent authority shall make suitable arrangements to ensure its independence from conflicts of interest between regulation of safety and environmental protection, and functions relating to economic development of the member state, in particular licensing of offshore oil and gas activities, and policy for and collection of related revenues."

This requirement is critical and some of the existing national offshore regulation authorities will have to be restructured to clearly separate revenue-generating and resource management from safety and environmental supervision.

Whistleblower clause. The Commission requires (in Art. 21 of the proposed regulation) the competent authorities in the EU countries to establish and implement procedures for allowing anonymous reporting of safety and/or environmental concerns related to offshore oil and gas operations and conduct subsequent investigations, while protecting the anonymity of the individuals concerned. This would improve, in conjunction with the transparence and reporting requirements discussed above, the accountability of the industry and the transparence of its offshore activities.

Lingering questions

On the other hand, the draft legislation leaves lots of grey areas, unanswered questions, and topics to be further developed. We briefly review below some of them.

Expand the coverage of the regulation. Although it is true that the oil and gas-related activities still dominate the offshore Europe marketplace, the EU and its member states have started to develop significant offshore renewable power generation capacity (mostly wind energy) and related transmission infrastructure. The EU also has significant plans to develop an offshore carbon capture and storage (CCS) infrastructure to move carbon dioxide by pipeline to depleted gas fields in the North Sea. In this context, as any energy-related activity entails risks, it would make sense for the European Commission to expand the coverage of the proposed regulation to include all offshore energy exploration, production, transportation and storage activities, so as not to discriminate against oil and gas offshore activities.

Revise current definitions. The proposed draft has some gaps in definitions of relevant terms and concepts. Some concept definitions should be clearer or better quantified. For example, in the definition of "major accident" (Art.2, paragraph 18), the Commission must quantify what "significant" means. Along the same lines, the definition of "major hazard" (Art. 2 paragraph 19) has to be quantified in order to clarify the reporting and emergency planning requirements. Other examples are the definitions of "offshore oil and gas operations" (Art. 2 paragraph 21) and "production installation" (Art. 2 paragraph 26). It is not clear if these definitions are covering applications such as the liquefaction and re-gasification of natural gas as part of the LNG value chain.

Clarify transboundary cooperation. The proposed draft mentions cooperation between neighboring states – offshore information exchange, major accident notice, etc (Art. 17), between member states (Art. 27) and between the EU and third-party countries (Art. 28). These articles are justified, but their language is vague and they will be difficult to implement if the relevant national regulatory frameworks are not harmonized.

Clarify response plans testing. The proposed draft requires that the offshore operators (Art. 29) and EU member states (Art. 30 and Art. 32) regularly test their preparedness to respond effectively to offshore oil and gas accidents. As this is a critical requirement, the regulation should clearly state the frequency of these tests, or at least which EU or national authority will determine what the testing frequency will be.

Define EU Offshore Authorities Group prerogatives. Although the proposed regulation requires the creation of the EU Offshore Authorities Group, it does not give a timeline nor define the main prerogatives of the new institution, or explain how it will be funded.

There are other topics that need clarification as well. Among them: is the EU going to provide special institution and regulation-building support to EU countries (for example Cyprus) and non-EU countries (for example Turkey) with an infant but growing offshore sector? Should the regulation include special requirements for the active installations that are currently beyond or close to their design life? Should there be any special requirements for decommissioning activities, which are covered by the proposed regulation, but only indirectly mentioned? Should the regulation include special requirements for offshore activities in deepwater versus shallow water? Will the EU adopt a "best available techniques" approach to encourage technological innovation in the offshore oil and gas sector? These questions now confront the EU and the European offshore oil and gas industry.

The author

Vlad Popovici is marketing manager at ShawCor Ltd., a leading global energy services company focused on solutions for oil and gas pipelines. Vlad holds an MBA (2005) from McGill University in Montreal and has been publishing technical articles and economic analyses since 1996.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com