Raul Vieira

Bureau Veritas North America Inc.

Sweeping changes are affecting offshore E&P activities in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GoM), spurred by the 2010 Macondo well incident. Perhaps the largest changes are from the U.S. government's Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), which established new Safety and Environmental Management Systems (SEMS) regulations.

SEMS builds on the American Petroleum Institute's API RP75, a recommended practice for developing a safety and environmental management program that was popular within the offshore sector starting in the mid-1990s. But SEMS, enacted in November 2011, takes this a step further by tying together all aspects of an offshore operation, including existing safety procedures, and assesses them to ensure that there are no gaps in the safety system that might lead to an accident. At its essence, SEMS is a systematic, comprehensive strategy to protect the health and safety of workers and the public, while safeguarding the environment.

All operators are legally required to have a SEMS plan in place for each of their offshore facilities, but it has proven easier for large, well-established operators with robust asset integrity management systems already in place. These systems may exceed SEMS requirements.

For smaller operators and independents with personnel, equipment, and resource limits, SEMS compliance proves more challenging. In addition, different operating systems typically have different asset integrity philosophies. A platform in shallow water may not require the same level of detail or complexity in its management system compared to an ultra-deepwater asset 200 mi offshore.

Yet for all these differences, there is a tendency to bring a "one-size-fits-all" approach to integrity management, whether the asset in question is a pipeline, a pumping facility, or a platform. An off-the-shelf solution may or may not be the most suitable, depending on the operator's experience, size, capabilities, and access to resources.

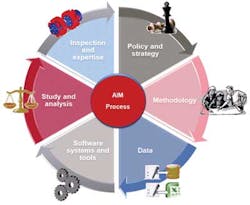

Experience demonstrates that a preferred asset integrity management system can be better developed with the execution of a series of technical audits of the operation. Bureau Veritas has developed a technical audit protocol that takes a holistic view of asset integrity management to provide appropriate technical recommendations for each asset. The process aims to not only identify gaps or areas of improvement to an existing integrity management system to ensure SEMS compliance, but also goes further to consider the asset integrity needs for the system throughout its lifecycle. It also offers technical solutions that are aligned with the philosophy of the company so that long-term operating objectives are met.

The following highlights some of the challenges operators face in implementing or upgrading an asset integrity management system, and how a gap-analysis technical audit provides the necessary information to make informed decisions that ensure compliance.

The track to compliance

The technical audit prescribed here goes beyond merely examining an asset's equipment. To ensure both regulatory compliance and long-term profitability, it is necessary to review the technical and operational capabilities of the company. This includes not only the physical condition of the asset, but also the company's processes and personnel.

A technical audit should begin with a clean slate, no presumptions of which systems or processes need to be aligned to meet a technical requirement until the entire asset has been studied. The audit is designed first to evaluate the current data and integrity management processes, and then to offer solutions that bridge the gap between what exists and what must be adopted to meet SEMS regulations and company expectations. In other words, the intent is to collect positive evidence of compliance as much as to identify potential gaps.

Data mining.The technical audit process begins with a thorough analysis of all data collected as part of the existing organizational structure. This analysis reviews not only the type of data available, but also how and where it is collected in the system, and then how it is applied.

This is not a trivial exercise. As asset integrity management systems have evolved over the years, both the volume and type of datasets generated and available for analysis have grown dramatically. Without a proper assessment of these datasets, an operator may follow an inspection recommendation that is impractical or prohibitively expensive. For example, an off-the-shelf integrity management software program might evaluate these large volumes of data to arrive at a recommendation that the operator should inspect structures every six months, which is an unreasonable schedule for any operator to fulfill.

Field findings. The next step of the audit moves to the field site to gain an understanding of how process management and equipment integrity is addressed currently, and how the data analysis feeds back into the system to drive integrity improvements.

This field analysis also reviews the relationship between the integrity management systems and the personnel charged with monitoring and maintaining them. A thorough understanding of the asset integrity management process at the field level is critical, as BSEE's regulatory personnel routinely visit offshore facilities and investigate workers' knowledge of the management program and how it ensures SEMS compliance.

To complete the process, the assessment investigates personnel competency, training, level of commitment to the programs, and how the organization communicates and disseminates SEMS policies.

The reporting process. In addition to training, SEMS brings a mandate for thorough record keeping of the entire asset integrity management system. While most documents and records need to be kept for six years, job safety analyses, injury/illness logs, and contractor evaluations must be kept for at least two years.

The technical audits are designed to not only review how the proper records are collected and maintained to ensure compliance, but also to review how these records are used to help ensure the ongoing safety of the asset.

Recommendations based on risk tolerance

With this analysis complete, the audit then shifts to the recommendation phase, in which several potential solutions are offered to the operator that, if implemented, would help achieve (or exceed) SEMS compliance.

If one thinks of the audit process as a medical examination, wherein the data gathering and analysis phases identify the "pain points" in an asset, then the recommendation phase is designed to offer the appropriate cure. However, while the cure must provide a remedy to ensure SEMS compliance, it need not be so comprehensive as to completely remove every symptom.

It is here that risk management comes into play for the operator. The operator must be offered one or more solutions that work best for the particular asset to alleviate the pain of being out of compliance with SEMS, but also to allow them to tolerate some pain, or risk, so long-term profitability is not compromised.

The recommended solutions must also account for several potential hurdles to implementation:

- Cost. The technical audit must strike a balance for a new asset integrity management system between its impact on ensuring the long-term viability of the asset, and on its implementation and operating costs.

- Supply chain. SEMS compliance does not only rely solely upon how one operates, but also on how one interacts with the entire supply chain. The operator must ensure a seamless supply of the materials and technologies required to maintain compliance, but also must make sure the costs are acceptable.

- Culture.The appropriate solution must overcome the "this is how it has always been done" mindset, to get people at the field level to engage in new asset integrity processes and technologies. The mandatory SEMS compliance must be instilled in every employee to ensure that the appropriate attitude and action toward asset integrity is achieved.

- Shareholder buy-in.A company cannot merely talk about SEMS compliance… it must live and prove it. Oil and gas companies will be required to audit their own SEMS plans within two years after they go into effect, and every three years thereafter.

In addition, the plans will be subject to audits by BSEE, which will require at all levels close adherence to operational and safety procedures that comply with SEMS plans. Failure to comply may mean the operator is delayed on project startup; if you are a non-compliant operator, this may find you out of a job. Failure to comply reaches all the way to the executive level; in Europe, non-compliance that leads to an environmental spill may lead to prison time for all employees—from the field engineer to the senior executive.

SEMS compliance is not merely an inconvenience… it is a reality. Adhering to this reality requires a technical audit process tailor-made to each asset, and offers technical solutions that are cost-effective, easy-to-implement for all players and have the appropriate support at the executive level. Without this process in place, operators may find themselves not only inconvenienced by fines or delays, but also completely prevented from operating altogether.