Operators to step up Caspian Sea production

Chris Boulter

Peter Kiernan

Roger Knight

Infield Systems Ltd.

As the largest enclosed body of water on Earth, and with petroleum reserves in excess of 50 Bboe, the Caspian Sea is a major offshore oil and gas province. Oil and gas activity in the region began with the drilling of the Bibi-Eibat field offshore Azerbaijan, which produces to this day. Since then, further discoveries have been made and developed, all of them in the shallow waters of the Absheron peninsula between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan in the southern portion of the Caspian Sea.

By the outbreak of World War II, Azerbaijan accounted for around 70% of the then Soviet Union’s petroleum production. Considered tactically vulnerable, and with Germany targeting Baku for capture, the Soviets evacuated the area and moved 11,000 oil specialists to the Tatarstan province in the Volga-Urals region, which subsequently was nicknamed “a second Baku.” Following the end of WWII, production restarted in the Caspian Sea, and further discoveries have been made over the subsequent years.

Although causing significant disruption in the region, the break up of the then Soviet Union in the late 1980s galvanized the industry as the former Soviet states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan began to seek the investment and technical expertise of international oil companies (IOCs). By the new millennium, 10 major IOCs were active in the Caspian Sea, including supermajors such as Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, and Total. Activities also had extended to the harsher northern Caspian Sea with the discovery of the 569 MMboe Yurii Korchagin field in 2000.

Kashagan

The Kashagan oil field in the northern Caspian Sea was discovered in 2000 and 19 exploration and appraisal wells have been drilled since with an unprecedented 100% success rate. It is the largest oil field outside the Middle East, and the fifth largest in the world in terms of recoverable hydrocarbons (with reserve estimates in excess of 13 Bboe). However, the field’s great depth (15,000 ft or 4,572 m below sea bed), high sulfur (H2S) content, and high pressure reduce the recovery factor to 15-25%.

Furthermore, the shallow water depth and cold temperatures at the site are unsuitable for typical fixed or floating platform designs. Instead, offshore facilities are being installed on artificial islands, offering protection from pack ice movement and providing uninterrupted production capability. There are two main types of islands – large, manned hub islands in the center of the development protected by several ice barriers; and also a number of small, outer unmanned “drilling islands.” Hydrocarbons extracted will travel from the drilling islands through pipelines to the hub islands, where they will then be processed before transport to onshore facilities and subsequent export. During Phase I of the project, around half of the gas produced will be re-injected into the reservoir to maximize recovery.

The field is being developed by a partnership that includes Shell, Eni, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Inpex, Total, and the Kazakh state run KazMunaiGas, in a consortium known as the Northern Caspian Operating Co. (NCOC). Eni is responsible for Phase I of the project, and will be succeeded by Shell as the field moves into more production phases. The complexity of the project has seen costs repeatedly rise for Phase I, and total development costs are currently estimated to be $136 billion, making it the most expensive oil and gas project in history.

The Phase II operator, Shell, has striven to reduce future capex and announced in late 2010 a reduction in costs of over $18 billion. An initial onstream date of 2005 has been repeatedly pushed back, and Kashagan now forecasts production to begin in 2012.

ACG

The Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (ACG) development is a large complex of fields offshore Azerbaijan at a water depth of approximately 125 m (410 ft), significantly deeper than northern fields such as Kashagan. Gunashli Deep was discovered in 1977, followed by Chirag in 1985, and Azeri in 1986. Total recoverable reserves in place are estimated to exceed 6 Bbbl of oil. The fields are operated by a BP-led multi-national consortium known as the Azerbaijan International Operating Co. (AIOC), and include SOCAR (Azerbaijan’s state oil company), Chevron, INPEX, Statoil, ExxonMobil, TPAO, Itochu, and Delta Oil Hess.

First oil was produced from Chirag in November 1997 and now incorporates three fixed platforms and over 60 production and injection wells. The slightly deeper Azeri field came onstream in early 2005 and has a field life estimated at approximately 30 years. It incorporates four piled fixed production platforms, and one central compression platform. The final field, Gunashli Deep, came onstream in April 2008 and was developed using two fixed platforms and over 30 subsea and surface wells. Gunashli Deep also incorporates several water injection wells intended to increase oil production during its 30-year life.

Oil from the Azeri and Chirag fields transfers to the onshore Sangachal terminal south of Baku via two separate pipelines, while Gunashli Deep oil is transferred via the Neftianye Kamni complex to the onshore Kyanizadag terminal east of Baku. There are plans for a possible oil pipeline in 2018, to export oil from these fields to Turkmenistan and further east to Asian markets such as China.

Growing onstream reserves and capex in the Caspian SeaSource: Infield Systems data.

Over $5 billion has been spent on the offshore infrastructure of ACG, and an additional $1 billion is expected to be spent over the next four years. Over 50% of this expenditure is to be on the largest field, Azeri. Unlike Kashagan, whose total capex will dwarf ACG, the development has been relatively straightforward, with relatively shallow water depths, little risk of sea ice, and location in a region that has 50 years of offshore platform experience.

Shah Deniz

The largest gas field in the Caspian Sea is 60 km (37 mi) southeast of ACG, in water depths varying between 80 to 600 m (262 to 1,968 ft). Shah Deniz is estimated to hold over 34 Tcf of gas, and almost 900 MMbbl of condensate.

Discovered in 1999, Phase I came onstream in late 2006 with one fixed platform, and it is expected to last for half a century. Phase II gas flows are expected in 2017 from up to three fixed platforms contributing to total capex for the project of $2.6 billion. In 2007, another deeper structure was found over 7,000 m (22,965.8 ft) below the surface, and was deemed viable for development in two stages.

Shah Deniz is operated by a consortium that includes BP as operator, Statoil, SOCAR, Total, LukAgip, NICO, and TPAO.

Gas and condensates are transported 100 km (62 mi) to the onshore Sangachal terminal, before being piped through the recently built South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP) into Turkey. It has a capacity for 20 Bcm/yr (706 bcf/yr) and can supply 5% of the EU’s gas imports. The Shah Deniz field also has been mooted as the prime initial gas source for the proposed Nabucco pipeline which, if completed, would stretch from Turkey into the heart of Europe. This pipeline project is aims to help diversify Europe’s energy supplies from a dependence on Russia. Furthermore, accessing Azeri offshore gas through a supply route that does not traverse Russia is seen as a key component of this policy.

The best of the rest

The remaining 48 fields so far discovered in the Caspian Sea account for an additional 13 Bbbl of liquids, giving a total in offshore reserves of over 53 Bbbl offshore Caspian. This highlights the significant amount of proved hydrocarbons present in the region, placing it in a prime position to supply local and international markets. The area also remains relatively unexplored – especially in the northern, harsher part of the Caspian Sea whose potential was so well underpinned by the discovery of Kashagan.

“Kash” money

Historically, Azerbaijan leads the region in offshore petroleum reserves, rising slowly to over 10 Bboe in 2000, with some contribution from Turkmenistan’s territory along the productive Absheron shelf. Capex has remained generally in line with reserve growth, with a noticeable decrease in the 1990s, a likely fall out from the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Development and first oil from the first of the large ACG fields (Azeri) in the late 1990s, and subsequent development of the Chirag and Gunashli fields a few years later, doubled Caspian Sea capex in the space of five years.

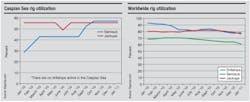

Although international oil companies have been active in the region for nearly 20 years, the next decade will see even greater oil and gas activity as reserves continue to grow and the region becomes a major oil and gas province. Continued development of the ACG complex and Shah Deniz projects in the south, and the Kashagan field in the north, as well as its large satellite fields, will see an Infield Systems growth estimate of over $4 billion annually in capex by 2016.

Pipeline installation accounts for a large proportion of capex over the next few years, with a significant rise in 2016 and 2017 due to two possible trans-Caspian pipelines in the south, along with further pipelines linking Shah Deniz and Kashagan to onshore terminals. A large proportion of remaining capex is predicted to go into offshore platforms, with fixed piled platforms still the installation of choice in the water depths experienced in the Caspian.

Towards the end of the forecast, floating platforms capex increases as development moves forward at the Kashagan satellite field of Kalamkas using barge-mounted units deployed to the drilling islands, in preparation for first oil in 2020. Subsea capex, meanwhile, is limited to the subsea developments at ACG and possibly Shah Deniz’s deepwater portions.

The Kashagan field, as well as significantly increasing Kazakhstan’s reserves, is predicted by Kazakh authorities to require over $136 billion in investment over its 40-year life.

Cold as ice

Although it shares its latitude with the sunny wine regions of southern France, the northern Caspian Sea can experience temperatures below -30ºC (-22ºF) in winter. Low salinity, due to the in-flow of fresh water from the Volga River, together with shallow waters and low temperatures means the northern Caspian freezes over for nearly five months of the year. In contrast to the waters of the Arctic Ocean, water depths in the northern area are very shallow, rarely over 7 m (22 ft), resulting in thin, fast-drifting ice than can change direction and speed rapidly. Ice also piles up in shallow areas and against drilling platforms, forming rubble piles up to 10 m (32 ft) thick.

These conditions create an ultra-harsh, arctic-like environment for offshore oil and gas operators, significantly increasing the difficulty of year-round operations where almost 50% of the Caspian Sea’s reserves are found.

The 570 MMboe Yuri Korchagin field in Russia was the first in the Caspian, and the world, to use an ice-class floating storage offloading vessel (FSO). Able to withstand ice conditions of -20ºC (-4ºF) and ice thickness of 0.6 m (2 ft), the FSO worked in tandem with two linked offshore ice-resistant platforms, LSP-1 and LSP-2, which rested on the sea floor. LSP-1 was based on the Shelf-7 semisubmersible design (active in the Caspian) and incorporated a “skirt,” protecting the risers and platform legs from ice flows.

The other high profile offshore development to manage cold temperatures and sea ice was Kashagan, where artificial islands and ice barriers were built in very shallow water depths. The world’s first ice-class drilling barge also was used to drill on the development, incorporating four-meter (13-ft) high curved ice deflectors and 24 piles driven 27 m (88.6 ft) into the sea floor, breaking up ice before it reached the platform and preventing ice pile up against and onto the barge.

At present, there are five ice-breaking supply vessels (IBSVs) operating in the northern Caspian Sea, serving Kashagan, and other offshore developments such as Yuri Korchagin. Of particular note are the Aker Arctic designedArcticaborg and Antarcticaborg, IBSVs specially designed with shallow draughts to operate successfully in the Kashagan area. The Kogalym and Langepas are multi-purpose duty rescue vessels able to travel through ice up to 0.7 m (2.3 ft) thick in -20ºC, serving Lukoil’s seven fields in the Caspian Sea.

Market maker

The Caspian Sea lies at the center of the new world. To the west lies Europe, importing over 10 MMb/d of oil. Relative political stability, developed infrastructure, and an established oil and gas market signals an attractive destination for Caspian petroleum. To the east lies China, importing over 4 MMb/d, and with an annual oil consumption growth of over 5% in the last 10 years.

With such a vital resource region between the EU, Russia, China and the Middle East, and with demand ever increasing, the Caspian Sea may come under increasing geopolitical pressure in the future. China, for example, experienced a natural gas shortage exceeding 32 Bcf in 2010 according to information from the South China Coal Trading Centre. The Caspian Sea holds 123 tcf of natural gas, and therefore China is eagerly awaiting the 2013 completion of the pipeline across Kazakhstan along a similar route to the existing Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline.

To the west, European nations consider the Caspian region as a lynchpin for efforts to diversify from Russia as a source and conduit of supply.

Looking ahead

Although the Caspian Sea is half the size of the North Sea, it is comparatively unexplored. The arctic-like northern sector has experienced exploration only recently while the region to the south of Baku remains relatively untouched due in part to territorial disputes with Iran. These revolve around whether the Caspian is “legally” a sea or a lake. If it is a sea, the nations surrounding it can divide it into separate national sectors. If it is legally defined as a lake, all of the resources might need to be divided fairly, in this case into five. In other words, if Iran, for instance, could get the Caspian Sea ruled as a lake, by definition, it could make it possible for Iran to claim 20% of Kashagan’s reserves and revenues.

Nonetheless, as revenue from growing petroleum exports flows back into the region, oil and gas activities will only increase, further enhancing the region’s international profile as an emerging petroleum power-house.

Offshore Articles Archives

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com