Shell moves to protect marine mammals offshore Alaska

Mark Kosiara, Michael Macrander, Ian M. Voparil - Shell

Development in the Alaskan arctic offshore requires meeting technical challenges as well as managing special environmental sensitivities related to cold regions with lots of biological diversity. The Beaufort and Chukchi seas are home to a variety of whales, seals, and other marine mammals that may be sensitive to the sounds of industrial activities.

Whales migrate into the area during the time of year when seismic operations are possible over the outer continental shelf (open, ice-free water usually the late summer and early fall). Bowhead whales, classified as endangered under US regulation, first migrate eastward in the late spring along the coast of the North Slope toward the Canadian Beaufort as leads in the ice pack develop. They return westward in the fall before the Beaufort is covered with ice. The short window of ice-free conditions means that offshore operations cannot simply be rescheduled to avoid the whales’ migrations, but must be evaluated in near real time so impacts are detected and mitigated when necessary.

Shell has extensive experience in the arctic, which contains an estimated 25% of the world’s remaining oil and gas resources. From Shell operations in Russia, Norway, Canada, and Alaska, the company has acquired substantial and growing experience in the technical, environmental, and social challenges unique to the arctic. That includes a long history in Alaska, where, beginning almost 50 years ago, Shell operated continuously until 1998.

Shell returned to Alaska in 2005 to participate in an offshore lease sale in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea. Through this, subsequent acquisition work, and joint venture, Shell is now the largest leaseholder in the Alaska Beaufort Sea.

In 2006, Shell performed a seismic program in the Chukchi Sea, with a limited shallow hazards survey in the Beaufort Sea; other operations were cancelled due to unfavorable ice conditions. In 2007, Shell conducted two 3D seismic acquisitions (one in the Chukchi Sea and one in the Beaufort Sea) and a number of developmental assessments including shallow hazards surveys. Shell also planned to drill two exploratory wells in the Beaufort Sea, but these plans were put on hold pending resolution of a legal challenge to the environmental assessment produced by the Minerals Management Service (MMS). Shell placed a priority on preventing injury to marine mammals by sound produced by offshore operations. This involved proactively limiting sound. For example, before the seismic program even went to sea, Shell worked with the geophysical company to limit the size of the seismic energy source to only that required to meet the technical objectives, to maximize downward propagation of sound energy, and to minimize horizontal leakage by tuning the airgun array’s components.

In addition, Shell designed a marine mammal monitoring and mitigation program with scientific tools, including vessel-based marine mammal observations, aerial overflights to spot marine mammals, and two different networks of seafloor recorders: 28 on-bottom hydrophones (OBHs) in the Chukchi Sea recorded ambient sound, the sounds produced by Shell’s activities, and the vocalizations of marine mammals. A network of 35 directional autonomous seafloor acoustic recorders deployed in the Beaufort Sea provided similar information as the OBHs, as well as triangulated positions of the vocalizing marine mammals that offered more detail on the migrations of marine animals past Shell’s operations.

Monitoring, mitigating effects of exploration

On-board marine mammal observers (MMOs) provided the most basic and essential monitoring and mitigation. Trained observers (including both scientists and Inupiat personnel) observed from the deck of all vessels during daylight. They recorded data on the presence and behavior of marine mammals near operations. They also had the authority to direct vessel movements and activities if there was concern that marine mammals could be affected. If marine mammals were observed within sound “safety zones” around vessels where sound exceeded regulatory thresholds, MMOs could direct either mitigative measures, which include evasive maneuvers, or shutdown of operations. Shell validated safety zones around the seismic vessel’s source of airguns within which received pulse levels were ≥ 180 dB re 1 μPa (rms) for cetaceans (whales and dolphins) and ≥ 190 dB re 1 μPa (rms) for pinnipeds (walrus, sea lions, and seals). These criteria assume that seismic pulses received at lower levels will not injure these animals or impair these animals’ hearing abilities, but that higher received levels might have some such effects. MMOs had the authority to shut down airgun operations if marine mammals were seen too close to the seismic vessel and source. By stationing at least one MMO on the bridge of the vessel, MMOs could communicate directly with the captain to insure protective measures occurred as quickly as possible.

Ramp-ups, shut-downs

A ramp-up of the array of seismic airguns occurred whenever airguns start firing, such as at the beginning of the season, after a shut-down, or if they have been turned off for any reason. A ramp-up provides a gradual increase in sound levels, and involves a step-wise increase in the number and total volume of airguns firing until the full volume is achieved. Ramp-up occurs at a rate not greater than 6 dB per 5-minute period and must be preceded by at least 30 minutes of marine mammal-free observation by the MMOs. The purpose of a ramp up is to warn marine mammals in the vicinity and to give them time to leave the area.

A “power down” is the immediate reduction in the firing of the airgun array from all guns to one firing airgun. A shut-down is the immediate cessation of firing of all airguns. The airgun arrays were immediately powered down (i.e., reduced to one airgun firing) whenever a marine mammal was sighted within a safety zone of the full airgun arrays but outside the safety zone of a single airgun. When a marine mammal was sighted within the applicable safety zone of the single airgun, no airguns were fired.

Aerial overflights

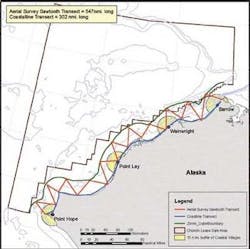

Aircraft carrying trained MMOs flew grids across the coastlines of the Chukchi and Beaufort seas, recording species, location, and behavior of marine mammals. These observations provided both the broad-scale patterns and distribution of marine mammals across the project areas, and narrow-scale patterns of distributional and behavioral reaction to operations.

In the Chukchi, transects were flown in a saw-toothed pattern extending from the coast to 20 mi (32 km) offshore from Point Barrow to Point Hope, which covered the boundary of the nearshore extent of the Lease Sale Area. Survey altitude was at least 305 m (1,000 ft) with an average survey speed of 100-120 knots. Survey altitude and vessel flight speed limits (305 m/1,000 ft minimum and 100-120 knots, respectively) minimized disturbance to marine mammals. MMOs looked for marine mammals within 1 km (0.6 mi) of the survey track. When sightings were made, observers recorded the species, the number of animals, and the lateral distance from the flight path. This, along with time and location from an onboard GPS, went into a database. Environmental data that affected sighting conditions, including wind speed, sea state, cloud cover or fog, and severity of glare, were recorded for each transect line or whenever conditions changed substantially.

In the Beaufort, aerial surveys were flown before, during, and after Shell’s operations to monitor and to mitigate any effects of seismic and shallow hazards site assessment activities on marine mammals, particularly Bowhead and Beluga whales. The surveys were moved east or west along the coast in tandem with Shell’s activities. These surveys provided information on the numbers of marine mammals potentially affected by the seismic program, and offered near real-time mitigation to prevent deflections of Bowhead whales migrating along the Beaufort Coast. During certain times of the 2006 and 2007 seasons in Arctic waters, US regulators required monitoring of Bowhead whales within an area around seismic operations ensonified to levels above 120 dB re 1 μPa (rms). As in the Chukchi, MMO sightings were combined with environmental observations and automatically generated positioning information. Observations included species, number, size/age/sex class when determinable, activity, heading, swimming speed category (if traveling), sighting cue, ice conditions (type and percentage), and inclinometer reading. The database provided information in units suitable for statistical analyses of effects of these variables (and position relative to seismic vessel) on the probability of detecting animals.

Because the MMS has long conducted aerial monitoring of the Bowhead whale migration within the Beaufort Sea, Shell’s program was designed to complement existing work (so that comparison to a long history of information would be possible) and to supplement coverage with a finer grid of transects during the whales’ migration west during seismic exploration. Purposes of the 2007 monitoring program were to provide data to determine how many marine mammals of each species modified their behavior due to the seismic program, the nature of those behavioral changes, and their likely consequences for the marine mammal populations. Regulations required these data to ensure that the seismic program had no more than a negligible impact on species or stocks of marine mammals, and no unmitigable adverse impact on their availability for whaling.

Networks of seafloor recorders

Shell deployed networks of seafloor acoustic recorders in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas to collect sound data that were analyzed after the instruments were recovered at the end of the season. Twenty-eight on-bottom hydrophones (OBHs) in the Chukchi Sea recorded ambient sound, the sounds produced by Shell’s activities, and the vocalizations of marine mammals. A network of 35 directional autonomous seafloor acoustic recorders deployed in the Beaufort Sea provided similar information as the OBHs, as well as triangulated positions of the vocalizing marine mammals for more detail on the migrations of marine animals. Compared with aerial surveys, acoustic methods have the advantage of providing a vastly larger number of whale and other marine mammal detections, and can operate day or night, independent of visibility, and to some degree independent of ice conditions and sea state, all of which prevent or impair aerial surveys. Acoustic methods, however, depend on the animals calling, and to some extent assume that call rate is unaffected by exposure to anthropogenic sounds. For example, Bowheads do call frequently in fall, but there is some evidence that their calling rate may be reduced upon exposure to airgun sounds, complicating interpretation.

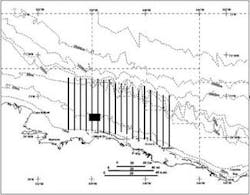

In the Chukchi Sea, lines of autonomous on-bottom hydrophones (OBHs) were deployed along four transects from approximately Pt. Hope to Pt. Barrow, Alaska. The specific geometries and placements of the arrays were driven primarily by three objectives:

- 1. To detect the occurrence and approximate offshore distributions of Beluga whales from July to mid-August and Bowhead whales from mid-August to late October.

- 2. To measure ambient noise.

- 3. To measure received levels of seismic sound energy.

Because each OBH had only one hydrophone, animal calls could not be localized or triangulated to determine an exact position of the individual, but instead offered a simple means to determine if vocalizing animals were present. Twenty-four OBHs were distributed at each of the four primary locations: Cape Lizborne, Point Hope, Wainwright, and Barrow. At each transect, OBHs were placed at 5, 10, 15, 20, 35, and 50 nmi (9, 18.5, 28, 37, 65, and 93 km) from shore at each location. The remaining 6 OBHs were distributed further offshore in the central Chukchi Lease Sale Area.

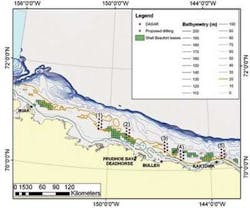

In the Beaufort Sea, 35 directional autonomous seafloor acoustic recorders (DASARs) were deployed. DASARs take bearings on marine mammals’ vocalizations. When the same vocalization is detected by multiple DASARs in the array, the location of the vocalization can be interpreted. The DASAR deployment was designed to detect vocalizations of migrating Bowhead whales and to investigate the behavior, specifically deflection or avoidance, near drilling and seismic operations. During an experimental program in 2006, more than 13,000 individual vocalizations were plotted from less than two weeks deployment of four DASARs.

The data from Shell’s 2007 program are being analyzed at this time. The dataset is extremely large, comprising several Terabytes of acoustic data. Analyses required refinement of automated, computer-based vocalization detection algorithms which should be usable in future research in the Beaufort and Chukchi seas.

Passive acoustic monitoring

For the 2006 program, Shell also employed an acoustic program that consisted of a series of ship surveys where a vessel-towed hydrophone system, called a Passive Acoustic Monitoring System (PAMS), collected data on the distribution and abundance of vocalizing whales in open water away from the coast. “Passive” monitoring means that listening for natural sounds produced by animals and attempting to triangulate a position using the different arrival times at three or more hydrophones rather than trying to determine an animal’s position by reflected sound (active acoustics). Three surveys were conducted during the 2006 open water season. The survey route covered a large portion of the OCS Chukchi Sea Lease Sale Area and remained in waters of similar depth. Repeating the route for each survey enabled detection of possible seasonal differences in sighting rates and densities.

Acknowledgements

Shell recognizes the significant contributions of LGL Alaska Research, JASCO Research, and Greeneridge Sciences Inc. to the Alaska Marine Mammal Monitoring and Mitigation Program for 2006 and 2007.

Authors

Mark Kosiara has a BS in Geological Engineering and an MS in Environmental Engineering and joined SEPCo in 1989. Kosiara held positions as a geological engineer, geophysicist, sub-surface team leader and as an environmental advisor in SEPCo. In 2001, Kosiara became the SIEP sustainable development advisor for the EP business, based in The Hague. Since 2004 he has been an environmental & sustainable development advisor in EPT-Projects. He currently is seconded to The Americas region acting as the Health, Safety, and Environmental lead for work in Alaska.

Ian Voparil joined Shell in 2005 as an environmental consultant focusing on marine topics, offering science-based advice on environmental issues and regulations. He has a BA from Boston University, PhD and MS degrees in oceanography from the University of Maine, and was a lecturer and researcher at the University of California Santa Cruz before joining Shell. He works in the Environmental Ecology and Response group of Global Solutions based in Houston.

Michael Macrander joined Shell in 1991. He has a BS from Tarkio College, an MS from Northern Arizona University, and a PhD from the University of Alabama in Ecology. He has more than 20 years of experience as an ecologist investigating environmental impacts and restoration of natural systems altered by human and industrial activities. He works in the Environmental Ecology and Response group of Global Solutions based in Houston.